In the China Story Yearbook 2014: Shared Destiny, we take as our theme a concept emphasised by Xi Jinping 习近平, the leader of China’s party-state, in October 2013 when he spoke of the People’s Republic being part of a Community of Shared Destiny 命运共同体, officially translated as a Community of Common Destiny. The expression featured in Chinese pronouncements from as early as 2007 when it was declared that the Mainland and Taiwan formed a Community of Shared Destiny. Addressing the issue of China’s relations with the countries that surround it at the inaugural Periphery Diplomacy Work Forum held in Beijing on 24 October 2013, Xi Jinping further developed the idea when he summed up the engagement between the People’s Republic and its neighbours by using a series of ‘Confucian-style’ one-word expressions: positive bilateral and multilateral relationships were to be based on amity 亲, sincerity 诚, mutual benefit 惠 and inclusiveness 容.

Shared Destiny has become a catchall category for the country’s regional and broader global engagement at a time when the People’s Republic of China is under the leadership of a focused, powerful and articulate leader. It provides substance and diplomatic architecture to the revived concept of All-Under-Heaven or tianxia 天下, one which assumes a belief that China can be a moral, political and economic great power.

In the China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China, we noted the efforts by Chinese international relations thinkers to rejig dynastic-era concepts and expressions so that the Communist Party can assert uniquely ‘Chinese ideas’ in world affairs. Otherwise vainglorious attempts to promote such formulations are now backed up by immense national wealth, and they may gain some traction. The historian Wang Gungwu 王赓武 has written incisively about All-Under-Heaven in contemporary China; among his observations is the following:

From China’s point of view, talk of a ‘peaceful rise’ suggests that a future rich and powerful China might seek to offer something like a modern vision of tianxia. This would not be linked to the ancient Chinese empire. Instead, China could be viewed as a large multinational state that accepts the framework of a modern tianxia based on rules of equality and sovereignty in the international system today.

… this overarching Confucian faith in universal values was useful to give the Chinese their distinctiveness. As an ideal, it somehow survived the

rise and fall of dozens of empires and provided generations of literati down to many modern intellectuals with a sense of cultural unity till this day.

Worrying about China

But there is anxiety associated with tianxia and its Shared Destiny as well. These grand notions do not address the many concrete problems associated with the pace and direction of the country’s reforms, about which many Chinese analysts expressed frustration in the lead-up to Xi Jinping’s investiture as the head of China’s party-state and army in 2012–2013. In essays and long analytical works they raised concerns about the perceived policy malaise of the Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 – Wen Jiabao 温家宝 decade of 2002–2013. They wanted the new leadership to confront the need to transform further the country’s political and economic systems, address pressing social issues, take an active role in the information revolution and be decisive in improving the regional and global standing of the People’s Republic.

In the late 1980s, as a decade of China’s Reform and Open Door policies began to remake the country, anxieties over social change, economic inequalities, environmental degradation, weakness on the global stage and a sclerotic political system generated the first major wave of post-Mao ‘crisis consciousness’ 忧患意识, or what Gloria Davies calls ‘worrying about China’. As the events of 1989 and beyond would prove, people had good reason to be worried. Even during the excitement and popular mood of national self-congratulation in the lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a new wave of ‘China worry’ was sweeping the People’s Republic.

Both publicly and privately, commentators expressed doubts about the ability of the political class — the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party — to deal with the vast array of challenges that China faced as a major world economy and potential world power: were they even moving China in the right direction? As in so many earlier eras, the second decade of the twenty-first century sees Chinese thinkers ‘worrying about China’: its scale, its problems and its future. At the same time, more than ever before, these issues have a global impact. Whether with regard to the environment, social change, political movements or economic growth, what happens in China is of growing concern to people everywhere.

Among the many critics who painted the Hu–Wen decade as lacklustre, there were those who wanted a stronger Communist Party, one with more purpose and capable of taking action against endemic corruption and the moral decline caused by the commercialisation of both the economy and society. Some were nationalists who opposed ‘pro-Western influences’ that encouraged the dangerous rise of civil society. Their views were countered by those who hoped that a change in leadership would usher in a period of extensive political and legal reforms, greater official accountability and media openness. Still others believed that a program of limited reforms managed by a strong party was the best hope for China’s future. In our two previous China Story Yearbooks, we outlined many of these hopes, and their fates, be they for a revival of Mao-era austerity, mass politics and ideological control or for constitutional reform and new limits on the Party’s power. But whatever their ideological bent, and whether those who worry about China worry from within or without, they are all aware that the solutions will relate, one way or another, to China’s Shared Destiny with the rest of the world.

The Prosperous Age

Even as the latest wave of ‘crisis consciousness’ was cresting, the rising standard of living and unprecedented level of general prosperity also fostered an opposite sense — this one heartily embraced by the party-state — that China had entered a shengshi 盛世, a ‘Prosperous Age’, or an ‘Age of Harmonious Prosperity’ 和谐盛世. In 2005, during the Central Chinese TV Spring Festival Gala 春节联欢晚会 — the most watched television event in the Chinese calendar and an annual moment of celebratory, national cultural unity — one of the featured dance performances was called ‘Grand Celebration of the Prosperous Age’ 盛世大联欢. Two years later, the Taiwanese historian and writer Li Ao 李敖 declared in a speech at Tsinghua University in Beijing that China was enjoying its first true Prosperous Age shengshi 盛世 since the Han 汉 and Tang 唐 dynasties. (Ever the contrarian, Li pointedly overlooked the zenith of the Qing 清 period, 1644–1911, commonly recognised as the third great shengshi of Chinese history.) Also in 2007, the nationally famous singer Song Zuying 宋祖英 sang in a paean to the Seventeenth Congress of the Party that China was now ‘Walking Towards an Harmonious Prosperous Age’ 走向和谐盛世.

Yet as applied to the ‘golden ages’ of the Han, Tang and Qing dynasties, shengshi refers to universally acknowledged periods of remarkable social grace, political rectitude and cultural richness. The self-proclaimed Prosperous Age of today’s People’s Republic has been nearly a century in the making; its achievement is far more contentious.

The following semi-official statement provides a shorthand, popular definition of the term ‘Prosperous Age’ as it is presently used in the People’s Republic:

A nation can be said to be enjoying a Prosperous Age when it has realised certain achievements both in terms of its domestic affairs and international politics.

Internally it features economic prosperity, scientific and technological advancement, intellectual creativity and cultural efflorescence; internationally it features military might; booming trade and considerable influence.

The general definition of a Prosperous Age includes the following measures:

- Unparalleled military strength

- Unsurpassed economic prosperity

- Unsullied political life

- Unprecedented scientific and technological advancement, and

- Unprecedented international exchanges.

盛世,即一个国家内政外交均有建树时的状况:

内政方面:经济繁荣,科技发达,思想活跃,文化昌盛;

外交方面:军事强大,贸易繁荣,影响力大等等。

盛世的界定,一般来说为以下标准:

- 军事空前强大

- 经济空前繁荣

- 政治空前清明

- 科技空前发达

- 对外交流空前活跃.

Common sense would suggest that to declare a particular period or an era — especially one of rapid socio-cultural change — to be a Golden or Prosperous Age before it is over is ill-advised. (It also begs the question whether frenetic economic activity is the ne plus ultra of human endeavour.) Heroic figures, pivotal historical moments, crises and ‘tipping-points’ are usually far clearer in retrospect. In China’s modern history, however, both governments and individuals have been hasty to announce and hail enlightenments, renaissances and revivals. The current mood is exuberant albeit anxious.

Leading the China Dream

Upon assuming the position of General Secretary of the Communist Party in November 2012, Xi Jinping announced the leitmotif of what is expected to be the decade of his rule. It was the ‘China Dream’ 中国梦. Unlike the American Dream, the China Dream was less about individual aspiration than the dream of an economically, socially, politically, militarily and culturally revitalised Chinese nation. It is a dream that has been dreamt in China since the late-nineteenth century.

The speed with which Xi not only took the reins of power covering the Party, the state and the military surprised many observers both inside and outside China, as did his rapid establishment of supra-governmental bodies called Leading Small Groups 领导小组 to oversee his agenda in a range of policy areas.

Such groups, large and small, short-term and semi-permanent, have waxed and waned over the years. However, there is a history in post-1949 China of strong leaders establishing their own Leading Small Groups to push through change in the face of bureaucratic inertia or opposition. In the mid-1960s, Party chairman Mao Zedong 毛泽东 established a Central Cultural Revolution Leading Group 中央文革领导小组 to dismember both party and state mechanisms that he perceived as obstructing his radical socio-political agenda; he wanted the group to reinvigorate the revolution and crush bureaucratic obfuscation. As a result, by the early 1970s, the Party and the state were in such disarray that Mao had to bring Deng Xiaoping 邓小平, a man who had early on fallen foul of his Cultural Revolution Leading Group but a capable bureaucratic manager, back from obscurity to help run the country.

Deng himself established a series of leadership-like groups to formulate and implement policies for a country damaged by so many years of political extremism, educational collapse and administrative malaise. Although Deng was purged again in 1976, he returned to power and became the first major leader of the post-Mao era. The bureaucrats he had employed in leadership groups to rebuild a functioning state from the rubble of the Cultural Revolution would eventually guide the country into the new era of Reform and Opening Up inaugurated in late 1978. These achievements were documented in great (if highly fictionalised) detail in the forty-eight-hour docu-drama, Deng Xiaoping During the Historical Transition 历史转折中的邓小平. The series aired throughout China in August 2014 to commemorate the 110th anniversary of Deng’s birth and to celebrate his achievements in turning the country away from Maoist ideology and launching the reforms that continue to transform the Communist Party-led People’s Republic of China.

Directed by Wu Ziniu 吴子牛, a member of the once avant-garde Fifth Generation of Chinese film-makers, the series also extolled the establishment of China’s first Special Economic Zone in Shenzhen under what it showed to be the far-sighted and sagacious leadership of Xi Zhongxun 习仲勋, an ally of Deng Xiaoping — and the father of Xi Jinping, China’s new paramount leader.

Deng, in his day, worked hard to dismantle the personality cult of Mao Zedong, and to ensure through the forging of an ethos of collective leadership that new mini-Maos would not appear. The party-state leaders who followed generally adhered to that approach (even if Deng himself enjoyed an extraordinary level of one-man power until his demise in 1997). Xi Jinping, however, appears to be going in the opposite direction. In titular terms alone, he has amassed more titles and formal powers than any leader in the five generations of party leadership since the 1940s including Mao. He may well have more titles than any ruler of China since the Qing dynasty’s Qianlong 乾隆 emperor in the eighteenth century, one whose Prosperous Age Xi Jinping and his cohort are said to have realised and are planning to surpass. He is now effectively head of ten party-state bodies, from the Party and army, as well as the People’s Republic itself, to seven small leading groups. Only two years into power ‘Big Daddy Xi’ 习大大, as the official media has taken to calling him, had become China’s CoE, ‘Chairman of Everything’.

Yet speculation remains rife as to Xi’s motivations, and whether his neutering of large swathes of the state bureaucracy (the nemesis at times of powerful predecessors such as Mao, and Deng as well) did not narrow policy options, and damage crucial institutional support in the median- to long-term.

One among Many

Why has Xi Jinping acted with such pressing haste to amass power, impose his will on the system and encourage something reminiscent of a personality cult? And why is the mainland media presenting him more as primus than China’s primus inter pares? He is omnipresent: making speeches; posing for photographs with soldiers, workers, foreign leaders; demonstrating his ‘common touch’ by showing up (relatively) unannounced in neighbourhoods and cheap restaurants. Official commentators analyse and praise his language for its erudition and canny use of classical quotations, the state-run press holds up his celebrity-singer wife Peng Liyuan 彭丽媛 as a fashion icon and model of Chinese womanhood. The propaganda onslaught behind Xi’s popularity is savvy and social media-friendly. His elucubrations are already enshrined as the fifth milestone in the Party’s body of theory as ‘Xi Jinping’s Series of Important Speeches’习近平系列重要讲话; and there is even a mobile phone app named Study Xi 学习to facilitate people who want to delve into his wisdom on the fly and follow his official itinerary.

In February 1956, the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced the Cult of the Individual (or Personality Cult) that had thrived under the then recently deceased general secretary of the Party and premier Joseph Stalin. Khrushchev included in his condemnation such features of the cult as the repeated use of quotations from Stalin’s speeches and sayings that were used by bureaucrats as justifications for political action, the crushing of all forms of opposition by the secret police, an exaggeration of the role of the leader in Party history, the production of songs, entertainments and other public declarations of loyalty and adoration of the leader and so on. Some might reason that under Xi Jinping China is not witnessing a revived personality cult, indeed, the popularity of Big Daddy Xi still lacks the hysteria and adulation achieved by the Mao cult in the 1960s, but signs of what German thinkers once called the Führerprinzip (a belief that certain gifted men are born to rule; that they deserve unswerving loyalty; and, that they take absolute responsibility for their leadership) are in evidence. This is hardly surprising in a country where the Crown Jurist of the Third Reich Carl Schmitt enjoys considerable prestige among left-leaning thinkers.

As we noted in our China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China, Xi Jinping says China must learn to tell The China Story better. But under his dispensation, in an increasingly ideologically policed China, there is an unsettling possibility that everyone may have to repeat the same story. In recent years, independent creative writing and reportage has flourished in China, so it is hardly surprising that now the pumped up decibels of the official China Dream as well as the crafted China Story of the party-state threaten to drown out the recent polyphony of the country’s online graphomaniacs.

Will such renewed attempts to replace the many with the one enjoy success? It is worth noting that Xi has led the Communist Party’s Politburo in a number of study sessions devoted to Dialectical Materialism; it is equally sobering to recall what Simon Leys (the pen name of Pierre Ryckmans, the Australian-Belgian Sinologist who passed away in August 2014) said about this underpinning theory of the Marxist–Leninist state a quarter of a century ago (notwithstanding Slavoj Žižek’s dogged burlesque defence of an ideal Marxism–Leninism):

Dialectics is the jolly art that enables the Supreme Leader never to make mistakes — for even if he did the wrong thing, he did it at the right time, which makes it right for him to have been wrong, whereas the Enemy, even if he did the right thing, did it at the wrong time, which makes it wrong for him to have been right.

In previous years, when China’s many stories proliferated, ‘crisis consciousness writers’, including Deng Yuwen 邓聿文 and Rong Jian 荣剑, enumerated lists of ten problems facing China. Here we posit our own Ten Reasons for Chairman Xi’s unseemly haste since taking the reins of power:

- Chinese leaders have long identified the first two decades of the new millennium as a period of strategic opportunity 战略机遇期 during which regional conditions and the global balance of power enable China best to advance its interests.

- Given his history as a cadre working at various local, provincial and central levels of the government Xi Jinping is more aware of the profound systemic crises facing China than those around him.

- He is riding a wave of support for change and popular goodwill to pursue an evolving agenda that aims to strengthen party-state rule and enhance China’s regional and global standing.

- He faces international market and political pressures that are compelling China to confront and deal with some of its most pressing economic and social problems, in particular the crucial next stage in the transformation of the Chinese economy.

- His status as a member of the Red ‘princelings’, or revolutionary nomenklatura, encourages the personal self-belief if not hubris that his mission is to restore the position of the Communist Party as China’s salvation. Believing in the theory that history is created by ‘Great Men’, he considers himself l’homme providentiel whose destiny is to lead the nation and the masses — a kind of secular Messiah complex.

- Unless he can sideline sclerotic or obstructive forces and elements of the system, he knows he will not achieve these goals.

- He is aware of the seriousness of the public crisis of confidence in the Party engendered by decades of rampant corruption.

- He is sincere in his belief in the Marxist–Leninist–Maoist worldview, which is tempered by a form of revived Confucian statecraft that is popularly known as ‘imperial thinking’ 帝王思想.

- Resistance to reform (including of corrupt practices) by the bureaucracy can only be countered by the consolidation of power.

- The consensus among his fellow leaders that China needs a strong figurehead to forge a path ahead further empowers him.

In the process of expanding his power, Xi and his Politburo colleagues were handed a windfall when, in early 2012, the Chongqing security boss Wang Lijun 王立军, said to be in fear of his life after falling out with the city’s powerful Party Secretary Bo Xilai 薄熙来 and his (as it turned out) homicidal wife, Gu Kailai 谷开来, fled to Chengdu to seek asylum at the American Consulate. These bizarre events gave the incoming leadership a chance to purge a potentially dangerous (and popular) political rival all in the name of dealing with corruption and the abuse of power. Following the consolidation of his power, Xi proceeded to undertake a gradual elimination of prominent party and army leaders implicated in corrupt dealings (some would note that it was surprising that, given their prominent role in central politics, neither he nor his predecessor, Hu Jintao, had effectively addressed the problem before). By September 2014, some forty-eight high-level Communist Party cadres, military officials and party-state bureaucrats (that is, those ranked at deputy provincial or ministerial level or above 副省、副部、副军级以上干部) had been swept up in the post-Eighteenth Party Congress anti-corruption campaign led by Xi and Wang Qishan 王岐山, Secretary of the Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection. The highest level targets of the purge were the Hu–Wen-era Party Politburo member Zhou Yongkang 周永康 and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Xu Caihou 徐才厚. As this Yearbook was going to press, Zhou was sentenced to life in jail for bribery and revealing state secrets (terminal cancer allowed Xu to escape prosecution).

Tigers Too Big to Cage

It is noteworthy that all forty-eight ‘Tigers’ 老虎, that is high-level corrupt officials, are reportedly from ‘commoner’ 平民 families with peasant or similarly humble origins. None came from the ranks of Xi’s peers, the ‘Red Second Generation’ 红二代 — children of the Communist Party founders from the Yan’an era through to the early People’s Republic. Neither were they of the ‘Office-holders’ Second Generation’ 官二代 — the children of members of the first generation of high-level cadres (then defined as above Rank Thirteen in the Twenty-four Rank Cadre System 二十四级干部制) and members of the inaugural National People’s Congress and the National People’s Political Consultative Committee in 1954. (Although Bo Xilai belonged to the Red Second Generation and was a Politburo member, he fell foul of the system before Xi Jinping launched his campaign to kill tigers and swat flies.)

And so while an impressive number of the progeny of the Party’s gentry are rumoured to be implicated in corrupt practices, they appear to have enjoyed a ‘soft landing’ in the anti-corruption campaign: being discreetly relocated, shunted into early retirement or quietly ‘redeployed’. It’s all very comfy: business as usual.

What has been rather more unexpected, however, is that after nearly two years of the campaign, members of the privileged families of the party-state went on the record to state why they are above the grimy business of corruption. Members of this group have been of interest to The China Story Project for some years, and they featured in ‘Red Eclipse’, the conclusion to our China Story Yearbook 2012: Red Rising, Red Eclipse. In the closed system of China’s party-state these seemingly defunct members of the ageing party gentry, their fellows and their families should not be underestimated; they cannot be dismissed, as some would have it, as marginal figures or has-beens. Nor is it wise to overlook the fury that their hauteur and unthinking air of superiority provokes among those members of the bureaucracy without such lofty connections, or among China’s aspirational classes more generally.

In particular, members of the Red Second Generation, along with optimists of various backgrounds, privately argue that Xi Jinping has amassed power as a stopgap measure to enable him to deal with fractious Party colleagues. Among other things, and to assuage hardline attitudes at senior levels, he has conceded to repressive policies across the board of a kind not seen since the early months of Jiang Zemin’s 江泽民 decade of tenure from 1989. Over time, and with the inauguration of a new Politburo in 2017, it is reasoned, Xi will reveal his reformist agenda and guide China towards a major political transition. ‘Gorbachev Dreaming’ of this kind has offered respite for wishful thinkers for a quarter of a century. It continues to kindle hope even among some of the most hopeless.

Sagacious Revivalism

For the nomenklatura, the notions of All-Under-Heaven and Shared Destiny underpin the role of the Party in the state; they see these ideas as closely aligned with the Marxist–Leninist–Maoist ideology that justifies the Party’s leading role. While the formulation Shared Destiny might be relatively new, party thinkers have always emphasised that the Party gives political expression to a community of shared aspirations and values. In earlier eras the vanguard of this community was the revolutionary workers and peasants, and later the worker-peasant-soldier triumvirate of the Mao era. In the post-1978 reform era, Deng Xiaoping added intellectuals to the community and the Jiang Zemin decade of the 1990s folded business people and capitalists into its embrace as well. Under Hu Jintao, who led the party collective in the first decade of the twenty-first century, the Chinese Communist Party finally became a party of ‘all the people’ — an expression Mao and his colleagues denounced as revisionist in the 1960s when accusing the Soviet Union of having lost its revolutionary edge. But it is just this claim, that the Party represents the interests of the ‘Chinese nation’ 中华民族 including all the communities and strata of Chinese society, that forms the bedrock of Party legitimacy today. A renewed emphasis on the collective, on Party probity, on traditional values over Western norms, on quelling the boisterous Internet, repressing dissent with a vigour not seen since the post-4 June 1989 purge, uprooting the sprouts of civil society and persecuting people of conscience in every sphere, have even led some Beijing wits to call Xi Jinping’s China ‘West Korea’ 西朝鲜.

Party education and propaganda, or ‘publicity’ as China’s propagandists prefer to call it these days, is suffused with ideas of collective and Shared Destiny. The cover of this Yearbook includes many of their favourite terms in a word cloud in the shape of the Chinese character 共 ‘common’ or ‘co-joined’. From the Red Samaritan Lei Feng 雷锋 to the model martyr party member Jiao Yulu 焦裕禄, to PLA heroics, the ethos of the collective suffuses the public life of the People’s Republic. The contributors to this Yearbook examine this topic from various angles. Paradoxically, it was under the rubric of collectivity during the Maoist era that the greatest damage was inflicted on Chinese individuals and families. Today, China promises that its revived collective mentality, shored up by a piecemeal use of traditional political thinking, is the only way to realise national goals, even as many observers note that the collective aspirations articulated and pursued by the state will come at a high cost, perhaps making it impossible for Chinese society to become mature, modern, self-aware and politically responsible even as it becomes rich and prosperous.

In its stead, we see another Chinese leader drawing inspiration not only from modern political ideology but also from the tradition of state Confucianism to promote their vision for China. In our 2013 Yearbook, Civilising China, we noted attempts in the 1930s by the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek 蔣介石 to modernise the Republic of China by employing ideas and values from the Confucian past in his New Life Movement 新生活運動. Today, Xi Jinping refers to the body of thinking and practice that was used by dynastic leaders for over two millennium to re-introduce Confucian ideas about virtue, morality, hierarchy, acceptable behaviour, social cohesion and prosperity (the countervailing elements of Confucianism that supported dissent, criticism of excessive power and humanity are quietly passed over). A punctilious Xi Jinping has also called for the institution of new state ceremonies that will intermesh with numerous new regulations regarding how public officials should comport themselves and use public funds. In such pronouncements we find echoes of Chiang Kai-shek’s 1943 wartime book China’s Destiny《中國之命運》 (most probably ghost-written by Chiang’s party theorist, T’ao Hsi-sheng 陶希聖).

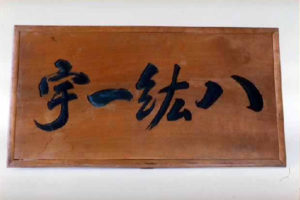

Prior to Chiang Kai-shek’s talk of destiny, joint concerns and regional harmony, in 1940 the Japanese imperial government, which made it clear that as Asia’s superior nation/race/military power/economy Japan was best placed to lead the region by expelling Western imperialism and imposing its own rule, announced that it would construct a Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere 大東亞共榮圏. The sphere would realise an age-old Japanese version of the tianxia vision of All-Under-Heaven. In Japanese this was called hakkō ichiu 八紘一宇, Eight Realms Under One Rule. It is hardly surprising then that with renewed talk of creating in East Asia a harmonious region or a Community of Shared Destiny, some recall the grand rhetoric, and failed ambitions, of that earlier era.

In November 2014, Xi Jinping returned to the topic of the Community of Shared Destiny during the APEC Summit held in Beijing. As this theme becomes further embedded in Chinese official discourse, and as China more confidently engages in global governance, an abiding element of China’s Maoist era — that of the collective outweighing the individual in every sphere of activity — will continue to shape the country’s behaviour internally, as well as externally. While many in Asia and the Pacific may indeed concede that they are bound by an economic shared destiny to the People’s Republic, it is hardly certain that China’s neighbours or trade partners will want to share entirely the increasingly confining vision of the Chinese Communist Party.

The China Story Yearbook

China Story Yearbook is a project initiated by the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) at The Australian National University (ANU). It is part of a broad undertaking aimed at understanding The China Story 中国的故事, both as portrayed by official China, and from various other perspectives. CIW is a Commonwealth Government–ANU initiative that was announced by then Australian prime minister, the Hon Kevin Rudd MP, in April 2010 on the occasion of the Seventieth George E Morrison Lecture at ANU. The Centre was created to allow for a more holistic approach to the study of contemporary China: one that considers the forces, personalities and ideas at work in China while attempting to understand the broad spectrum of China’s socio-political, economic and cultural realities. CIW encourages such an approach by supporting humanities-led research that engages actively with the social sciences. The resulting admix has, we believe, both policy relevance and value for the engaged public.

The Australian Centre on China in the World promotes a New Sinology, that is a study of China underpinned by an understanding of the disparate living traditions of Chinese thought, language and culture. Xi Jinping’s China is a gift to the New Sinologist, for the world of the Chairman of Everything requires the serious student of contemporary China to be familiar with basic classical Chinese thought, history and literature, appreciate the abiding influence of Marxist-Leninist ideas and the dialectic prestidigitations of Mao Zedong Thought. Similarly, it requires an understanding of neo-liberal thinking and agendas in the guise of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics 具有中国特色的社会主义. Those who pursue narrow disciplinary approaches to China today serve well the metrics-obsessed international academy, but they may readily fail to offer greater and necessary insights into China and its place in the world.

Most of the scholars and writers whose work features in Shared Destiny are members of or are associated with the Australian Centre on China in the World. They survey China’s regional posture, urban change, politics, social activism and law, economics, the Internet, cultural mores and arts, history and thought during the second year of Xi Jinping’s tenure as party-state leader. Their contributions cover the years 2013–2014, updated to December 2014, and offer an informed perspective on recent developments in China and what these may mean for the future.

Shared community, shared values, the imposition of collectivity — it is under such a system that difference is discriminated against, policed and coerced. The account in this Yearbook is a sobering one. We position our story between two plenary sessions of the Chinese Communist Party, the Third Plenum of the Eighteenth Party Congress in November 2013, which focused on economics, and which is the topic of Chapter 1 by Jane Golley, and the final chapter by Susan Trevaskes and Elisa Nesossi, which concentrates on the new legal regime under Xi Jinping, the theme of the Party’s Fourth Plenum in October 2014. In Chapter 2, Richard Rigby and Brendan Taylor look more closely at Xi’s foreign policy, an area which saw some major missteps in 2013 and 2014, perhaps due to what we might well call the Maoist style of Xi and his advising generals. This approach has been celebrated in the official Chinese media as a form of ‘foreign policy acupuncture’ 点穴外交. I would suggest that the general tactics used — action, reaction, recalibration, withdrawal — is a disruptive style that recalls Mao’s famous Sixteen-character Mantra 十六字诀 on guerilla warfare: ‘When the enemy advances, we retreat; when the enemy makes camp we harass; when the enemy is exhausted we fight; and, when the enemy retreats we pursue’ 敌进我退,敌驻我扰,敌疲我打,敌退我追. It is an approach that purposely creates an atmosphere of uncertainty and tension. To appreciate the mindset behind such a strategy students of China need to familiarise themselves with such Maoist classics as On Guerilla Warfare《论游击战》and On Contradiction《矛盾论》.

Chapter 3, by Jeremy Goldkorn, looks at the cordoning of the Chinese Internet from a world wide web that proffers a community of shared information, while in Chapter 4, Gloria Davies considers how official China talks to and about itself. In Chapter 5, Carolyn Cartier examines the shared destinies of people flooding Chinese cities from the countryside and the common spaces shared by Chinese tourists and immigrants around the world.

Chapters are arranged thematically and they are interspersed with information windows that highlight particular words, issues, ideas, statistics, people and events. Forums, or ‘interstices’, expand on the contents of chapters or offer a dedicated discussion of a topic of relevance to the year. These include an overview of the classical literary and cultural references in Xi Jinping speeches by Benjamin Penny; an essay on rules that seek to codify family values, in particular filial piety, by Zou Shu Cheng 邹述丞; a look at confusing times for foreign business in China by Antony Dapiran; a meditation on the concept of the right to speak or huayuquan 话语权 by David Murphy; portraits of Sino-Russian and Sino-European relations by Rebecca Fabrizi; a discussion of the United Front work of the Party by Gerry Groot; the politics of protest in Taiwan by Mark Harrison; official policy on the arts by Linda Jaivin; Chinese cinema by Qian Ying 钱颖; contemporary Chinese art by Chen Shuxia 陈淑霞; Chinese families going global by Luigi Tomba, and, finally, the topic of shared air by Wuqiriletu. The Chronology at the end of the volume provides an overview of the year under discussion. Footnotes and the CIW–Danwei Archive of source materials are available online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/dossier/.

Acknowledgements

The editorial group that has overseen this project, Geremie R Barmé, Linda Jaivin and Jeremy Goldkorn, has worked closely with Jeremy’s colleagues at Danwei Media in Beijing — Joel Martinsen, Aiden Xia 夏克余, Li Ran 李然, Jay Wang 王造玢, Tessa Thorniley and Joanna (Yeejung) Yoon — who provided updates of Chinese- and English-language material relevant to the project, as well as helped to compile the material used in the information windows in chapters. We are deeply grateful to Linda Jaivin for her extensive and painstaking editorial work on various drafts of the manuscript, and to Lindy Allen and Sharon Strange for typesetting. Markuz Wernli designed the book and cover image.

Cover of the China Story Yearbook 2014 with a word cloud, featuring expressions and official clichés in the shape of the character 共 gong

Artwork: Markuz Wernli

The Cover Image

The Yearbook cover consists of a word cloud in the shape of the character 共 gong, ‘shared’, ‘collective’ or ‘common’, followed by the three other characters that make up the expression Shared Destiny 共同命运, the theme of this book.

The word cloud features expressions and official clichés that have gained purchase, or renewed currency in the Xi Jinping era. For example, the top left-hand corner of the character gong includes such terms as: ‘self-cultivation’ 修身, taken from the Confucian classic The Great Learning《大学》; ‘breathing the same air’ 同呼吸; ‘sincerity and trust’ 诚信; and, ‘advancing together’ 共同前进. Or, in the top right-hand corner: ‘self-reliant and self-strengthening’ 自立自强; ‘exploit the public to benefit the private’ 假公济私; and, ‘mollify people from afar’ 柔远人. Other terms date from the Maoist era (1949–1978) of the People’s Republic or earlier, expressions that feature in Xi’s remarks on the Community of Shared Destiny, or in pronouncements contained in his ever-expanding ‘series of important speeches’.

As mentioned earlier, the Xi era is a boon for the New Sinologist: in today’s China, party-state rule is attempting to preserve the core of the cloak-and-dagger Leninist state while its leaders tirelessly repeat Maoist dicta which are amplified by socialist-style neo-liberal policies wedded to cosmetic institutional Confucian conservatism. The Yearbook word cloud cover, which employs the white-on-red palette used for billboards featuring party slogans and exhortations, was designed by Markuz Wernli and succinctly reflects this exercise in the incommensurable.

Notes

See Jin Kai, ‘Can China Build a Community of Common Destiny’, The Diplomat, 28 November 2013, online at: http://thediplomat.com/2013/11/can-china-build-a-community-of-common-destiny/

See ‘Xi Jinping: China to further friendly relations with neighboring countries’, Xinhua, 26 October 2013, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-10/26/c_125601680.htm

See ‘Xi Jinping: Let the Sense of Community of Common Destiny Take Deep Root in Neighbouring Countries’, Xinhua, 25 October 2013, online at: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/wjbz_663308/activities_663312/t1093870.shtml; and, Neil Thomas, ‘Rhetoric and Reality — Xi Jinping’s Australia Policy’, The China Story Journal, 15 March 2015, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/2015/03/rhetoric-and-reality-xi-jinpings-australia-policy/

See Richard Rigby, ‘Tianxia 天下’, in China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China, pp.75-79; online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/yearbooks/yearbook-2013/forum-politics-and-society/tianxia-天下/

Wang Gungwu, Renewal: The Chinese State and the New Global History, Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2013, excerpted online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/2013/08/wang-gungwu-王庚武-on-tianxia-天下/

For an overview of the anxieties of the 1980s, see ‘Crisis Consciousness: “China Problem Studies” ’, in Geremie Barmé and Linda Jaivin, eds, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Times Books, 1992, pp.165-170; and, for later worriers, see Gloria Davies, Worrying about China: the language of Chinese critical inquiry, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

Geremie R Barmé, ‘Shengshi Zhongguo 盛世中国 China’s New Prosperous Age’, China Heritage Quarterly, no.26 (June 2011), online at: http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/editorial.php?issue=026

See http://baike.soso.com/v538859.htm

See Alice Miller, ‘The CCP Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups’, China Leadership Monitor, no.26 (September 2008); and, Alice Miller, ‘More Already on the Central Committee’s Leading Small Groups’, China Leadership Monitor, no.44 (July 2014), online at: http://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/research/docs/clm44am.pdf

Simon Leys, ‘The Art of Interpreting Nonexistent Inscriptions Written in Invisible Ink on a Blank Page’, New York Review of Books, 11 October 1990, online at: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/1990/oct/11/the-art-of-interpreting-nonexistent-inscriptions-w/

Deng Yuwen, ‘Ten Grave Problems Facing China’, The China Story Journal, 8 September 2012, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/2012/09/the-ten-grave-problems-facing-china/; and, Rong Jian, ‘Ten Questions for China’ 中国十问, online at: http://www.gongfa.com/html/gongfashiping/201208/02-1975.html

See ‘Bo Xilai’, China Story Yearbook 2013, pp.210-211, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/yearbooks/yearbook-2013/chapter-4-under-rule-of-law/bo-xilai/

Geremie R Barmé, ‘Conclusion: Red Eclipse’, China Story Yearbook 2012: Red Rising, Red Eclipse, pp.271-274, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/yearbooks/yearbook-2012/chapter-10-red-eclipse/

From Geremie R Barmé, ‘Tyger, Tyger — a fearful symmetry’, The China Story Journal, 16 October 2014, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/2014/10/tyger-tyger-a-fearful-symmetry/

Geremie R Barmé, ‘Engineering Chinese Civilisation’, China Story Yearbook 2013, p.xiv, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/yearbooks/yearbook-2013/introduction-engineering-chinese-civilisation/

‘Xi Jinping: Establish a New System of Ceremonies and Promote Mainstream Values 习近平:建立礼仪制度、传播主流价值’, 26 February 2014, Xinwen chenbao, online at: http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2014-02-26/071029565316.shtml

Chiang Kai-shek, China’s Destiny & Chinese Economic Theory, With Notes and Commentary by Philip Jaffe, London: Dennis Dobson Ltd., 1947.

See http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1210451.shtml; and, http://www.dw.de/chinas-president-xi-touts-asia-pacific-dream-ahead-of-apec-summit/a-18050065

Chiang Kai-shek, China’s Destiny, pp.201-202, 210, 215, 217, 231 and 232.

See http://chinainstitute.anu.edu.au/morrison/morrison70.pdf

Geremie R Barmé, ‘New Sinology后汉学/後漢學’, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/new-sinology/