On 11 April 2016, a reporter for the National Business Daily 每日经济新闻 named Zhang Wen 张雯 wrote a worrying report titled ‘Ministry of Water Resources thoroughly investigates groundwater resources: eighty percent is not suitable for drinking’. According to statistics published by the Ministry of Land and Resources, more than 400 cities out of 657 nationwide are using groundwater for drinking water. That means seventy percent of the population is drinking groundwater, of which eighty percent is not suitable for drinking. However, soon after the report’s publication, Chen Mingzhong 陈明忠, Department Head of the Water Resource Division of the Ministry of Water Resources, responded that the reporter had misread the data. He said that, in fact, people in 1,817 out of 4,748 cities and towns are drinking groundwater with a water quality compliance rate of about eighty-five percent. One thing is certain, however: China is in a state of ‘water stress’, and one of the difficulties in the search for solutions to this pressing problem is that the available official data is often contradictory.

Figures on water quality in China have been in chaos for a long time. There is a discrepancy between what the media reports and the figures provided by government departments, between data provided by different government departments, and even within the same department. Scholars use the term ‘Nine Dragons Controlling Water’ 九龙治水 to describe China’s current chaotic water safety management system. This refers to the involvement, not always well co-ordinated, of multiple government departments in water management — a major reason for the confusing and conflicting data.

As shown in the table, water security information is fragmented and distributed across government departments, with considerable overlap. Rainfall, for example, is a concern of both the Bureau of Meteorology and the Ministry of Water Resources. These departments tend to be territorial about their data. There is no mechanism to facilitate the sharing of information between or within government departments, and no commitment to share the information fully with the public, which presents problems for both the journalistic and scientific communities, not to mention interested citizens.

Water source quality information disclosure by local governments (the provinces in grey have not disclosed any information) Source: dtcj.com

The Water Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan 水污染防治行动计划, also known as the Water Ten Plan 水十条, which the State Council released last year, was fully implemented in 2016. An important component of the Water Ten Plan is the requirement to publicise information on water quality. In January 2016, the Ministry of Environmental Protection issued a notice requiring local governments to disclose the results of their monitoring of water source quality in accordance with the National Centralised Drinking Water Source Quality Monitoring Information Disclosure Program 全国集中式生活饮用水水源地水质监测信息公开方案. The notice mandates the timely disclosure of information, and the use of channels including the websites of the Environmental Protection Department and local environmental monitoring agencies. The notice emphasises the importance of clearly presenting the data so that the public can understand the situation with their water quality. This is a major change from past practices, and a good starting point for responsible water management. It marks the transition of China’s water security information from an exclusive resource of government to one shared with the public. This is something that the media, academics, and ordinary people have looked forward to for years.

But not all local governments have reacted well to the order from above to share their data. At the end of the first quarter of 2016, the environmental NGO Qing Yue Database on Environmental Information 青悦环保信息技术服务中心 reported on the status of information disclosure by local governments. Only fifty-four percent of provincial governments had published data on their official websites. Even where they did publish, they didn’t provide all of the required information, such as the number of water sources monitored, monitoring points, monitored items, and monitoring methods. Without all this information, the public cannot fully judge the quality of their drinking water. The other forty-six percent, who have not disclosed any information at all, include the provinces of Sichuan, Anhui, Yunnan, Hebei, Shanxi, Ningxia, Jiangsu, Shandong, Zhejiang, and Hunan; the central cities of Tianjin and Beijing, the autonomous region of Tibet, and the Xinjiang Construction and Production Corps.

The Qing Yue Database on Environmental Information is intended to convey to the public information on water quality from the source to the taps. They have been frustrated by the number of departments and enterprises involved, and the low level of information disclosure. They drew the diagram below to illustrate the problem.

Information on water quality from source to tap

Image: Qing Yue Database on Environmental Information

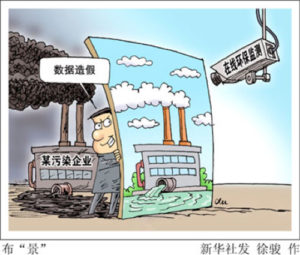

An even more serious issue is that, over the years, many local government departments and enterprises have deliberately recorded false data. Two years ago, Premier Li Keqiang 李克强 visited the Ministry of Water Resources. He told them that there needed to be a third-party assessment of government data on the safety of drinking water to prevent data fraud. On 1 January 2016, the Ministry of Environmental Protection finally introduced a procedure called the Determination and Treatment of Falsification of Environmental Monitoring Data.

On 14 April, the Xinhua News Agency in Beijing reported that over a twelve-month period, the Environmental Protection Department discovered 2,658 cases of environmental monitoring data fraud. In October, police detained a bureau chief from the Chang’an Branch of Xi’an’s Environmental Protection Bureau, as well as the chief and a deputy chief of the Chang’an District monitoring station, on suspicion of data monitoring fraud. This is the first case of legal sanctions against local government officials for data fraud since the implementation of the new law.

Notes

‘Ministry of Water Resources thoroughly investigates groundwater resources: eighty percent is not suitable for drinking 水利部摸底地下水资源: 八成不能饮用’, National Business Daily, 11 April 2016, online at: http://www.nbd.com.cn/articles/2016-04-11/996946.html

‘Ministry of Water Resources responded to the media: water quality of the water sources is gen- erally good 水利部回应’八成地下水不能饮用’: 水源地水质总体良好’, People’s Daily, 12 April 2016, online at: http://env.people.com.cn/n1/2016/0412/c1010-28268503.html

‘14 provinces have not disclosed data from drinking water protection zones in accordance with the requirements of the Ministry of Environmental protection 还有14省份没有按环保部要求公开 饮用水水源地水质信息’, 14 May 2016, online at: http://m.duxuan.cn/doc/4372782.html

‘Minister Chen Jining, the di culty of drinking water safety information disclosure may be beyond your imagination 陈吉宁部长,饮用水安全信息公开难度可能超出您想象’, H2O China (中国水 网), 17 March 2016, online at: http://www.h2o-china.com/news/238113.html

‘More than 2000 cases of environmental monitoring data fraud had found within a year 一年 揪出2000多起 钢牙咬出环保监测数据造假’, Xinhuanet, 14 April 2016, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-04/14/c_1118622028.htm

‘Number of local government o cials in Xi’an are taken away by police on suspicion of data monitoring fraud 西安多名环保官员监测数据造假被警方带走’, China News, 26 October 2016, online at: http://www.chinanews.com/sh/2016/10-26/8043403.shtml