CHINA’S ROLE in the multilateral trading system established under the auspices of the World Trade Organization (WTO) has been much debated and remains highly controversial. More often than not, however, the labelling of China as a ‘bad player’ in the system results from significant misunderstandings of both the WTO’s functions and China’s behaviour.

Amid the rising tensions between the United States and China since 2017, the Trump Administration frequently and aggressively repeated the claim that the US, under the Clinton/Bush Administration in 2001, mistakenly supported China’s accession to the WTO.1 It accused China of failing to adhere to WTO rules and failing to transform into a fully fledged market economy. It also accused China of refusing to implement the rulings of the WTO’s dispute-settlement system when it lost a case. The Trump Administration’s argument also blamed the WTO for failing to come up with ways to tackle China-specific problems such as these.2 The European Union (EU) and Japan have shared some of these concerns.3 However, these claims are untenable and misleading.

As a global institution, the WTO does not mandate any particular type of economic and political structure or model of development. Its members are at various stages of economic development, with different economic structures, policy priorities and regulatory regimes. Nor does the WTO require members to change the structure of their markets or patterns of ownership. While China may not have a free market economy,4 it is not unique: state-owned enterprises (SOEs) play a significant role in many economies and regulatory intervention in markets is widespread.5 The WTO and its predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1947–1994), have admitted many other transitional economies, including Poland, Romania, and Hungary in the 1950s and 1960s, and Russia and Vietnam more recently. When negotiating to join, China insisted on its own development model of a ‘socialist market economy system’.6 It is both unreasonable and unrealistic to expect or demand that China adopt a Western model of market capitalism. While its accession commitments involved massive market-oriented reforms, nothing in those commitments required China to change its economic model.

To join the WTO, China made unparalleled commitments. Then US Trade Representative (USTR) Charlene Barshefsky observed that the concessions it made ‘far exceeded what anyone would have expected’.7 To date, China’s obligations remain the most extensive and onerous among all WTO members, and many go far beyond those demanded of the most developed nations.8 To implement these obligations, China made tremendous efforts, including amending numerous laws and regulations, significantly reducing tariff and non-tariff barriers, opening up a range of service sectors and achieving outstanding and well-documented successes along the way.9 The USTR report on China’s WTO compliance in 2007, the year immediately after China was required to complete implementation of most of its WTO concessions, acknowledged that ‘China has taken many impressive steps to reform its economy, making progress in implementing a set of sweeping commitments’. It also noted that China’s WTO membership had delivered ‘substantial ongoing benefits to the United States’.10 Thus the claim that China failed to observe its WTO commitments is misleading.

This is not to say that China has never breached WTO rules. However, whether a member has breached a rule must be assessed through the WTO’s dispute-settlement mechanism (DSM), based on evidence and detailed legal examination rather than through unsubstantiated allegations.

Having been involved in many WTO disputes both as a complainant and as a respondent, China has become an experienced and sophisticated player in the DSM.11 When it was less experienced in the early years of its membership, China settled most of the disputes in which it was a respondent by amending or removing the challenged policies, laws and practices without going through the adjudication process. In the past decade, China has changed its approach to vigorously pursuing or defending selected cases.12 In almost all of the cases it has lost, China has implemented the findings and recommendations of WTO tribunals. It has done so in a way that delivers the minimum level of compliance required while maintaining its own interests, showing full comprehension of the limits of the rulings. Overall, China’s record of compliance compares favourably with those of the other key players in the system, and particularly the US. China has never been subject to any demand for retaliation (the final and most serious consequence that a member can face in the DSM). Yet the US has been a major target of retaliation, the most recent being a WTO-authorised retaliation worth US$4 billion by the EU due to its failure to remove subsidies to Boeing that are illegal under WTO rules — a dispute that has lasted for sixteen years.13

This is not to suggest that China poses no challenges to the multilateral trading system. Industrial policies and subsidies, the role of SOEs in the economy, the growing influence of the government on private enterprises and insufficient protections for intellectual property rights are prominent and long-standing issues. Although similar situations persist in other member states, China has been at the centre of academic and policy debate given the scale and impact of its policies and practices. In this regard, the global community has been overwhelmed by allegations that WTO rules are inadequate to cope with China. However, to determine whether the rules are in fact insufficient, one would have to undertake a meticulous study of the Chinese laws and practices in dispute and all the applicable rules including those specifically tailored to China. Contrary to the allegations of the Trump Administration, one such study has found that ‘the WTO’s existing rules on subsidies, coupled with the China-specific obligations, provide sufficient defence against the encroachment of Chinese SOEs beyond their own shores’.14 Therefore, the issue is perhaps not the lack of rules but the lack of utilisation of the rules.

WTO rules rely, of course, on enforcement. The DSM has managed nearly 600 trade disputes since commencing operations in 1995.15 It has been largely effective in enforcing compliance and influencing domestic policy-making,16 including in China, where its decisions have prompted gradual and systematic adjustments to the country’s complex regulatory regime. However, the ongoing crisis in the DSM — the result of the US under President Trump blocking the appointment of judges to the WTO’s Appellate Body (its appellate court) — has weakened the effectiveness of the system as a whole. In the absence of a functional Appellate Body, a losing party may abuse the right of appeal to avoid adverse decisions of WTO panels (the WTO’s lower court) and implementing their decisions,17 as several members have done in recent cases. As the most frequent abuser to date, the US, in two recent cases, ‘appealed into the void’ a panel ruling against the trade war tariffs it imposed on China,18 and another panel ruling against its anti-subsidy tariffs on softwood lumber originated in Canada — both in breach of WTO rules.19 Such abuse of the right of appeal will only further damage the DSM and encourage similar actions, furthering the crisis and generating more tensions and uncertainties in international trade.

The unilateral and confrontational approach of the US has in any case proven to be counterproductive in dealing with China. As China’s economic power and influence grow, its foreign policy is becoming more assertive, as is evident in its (relatively moderate) response to the US’s trade war tariffs and its ongoing trade sanctions against Australia.20 With China asserting that it is a staunch defender of the multilateral trading system,21 a co-operative approach would be more effective. But this would need to entail adopting an objective and country-neutral stance on China.

The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)

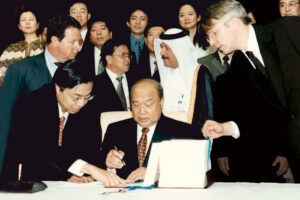

Source: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Flickr

As flagged above, the so-called China problems of industrial policies, subsidies and SOEs are also issues in many other member nations of the WTO. The COVID-19 outbreak has led many governments to resort to such policies as export restrictions, stimulus packages and subsidies to maintain domestic economic resilience and stimulate recovery.22 Global problems require global solutions based on collective efforts and actions that target the problems themselves. The WTO provides a unique forum for multilateral solutions: when a government suspects that China has not played by the rules, it should resort to the DSM to push China to change its behaviour. This approach has worked very well in the past, though it may not be as effective today given the impasse over the Appellate Body caused by Washington. If the WTO is to function properly, with regard to China or any other member state, it needs a functioning Appellate Body and rules that are based on multilateral negotiations and that reflect the shared interests of all nations involved.

The recent completion of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free-trade agreement to date, embracing 30 percent of global output,23 has shown the strong political will for international co-operation of the fifteen member countries, including China, even in times of crisis, populism, and anti-globalism. While the US’s trade policy agenda remains to be uncovered, there are some positive signs of moves towards a more co-operative approach to China and the WTO under the incoming Biden Administration.24 This approach will offer greater hope for working with China on the challenges faced by all nations and the multilateral trading system.