Last few weeks we have focused on social issues inside China. This week we switch focus to international developments outside China.

1. AUKUS

Much ado about nothing?

With hastily arranged top-secret meetings on a “major international development” and speculations ranging from aliens to imminent warfare, I felt kind of let down by AUKUS. But perhaps we should not have gotten so excited — while the imminent announcement became a major headline in Australia, it barely made the front page in the US.

Overall, AUKUS is unlikely to significantly change the regional strategic landscape. Australia is already closely aligned with the US. Incremental decisions by the government over the recent years have shown that Australia has already chosen a side in any conflict between the US and China. This merely confirms that.

And for China, it also understands that Australia has chosen. So this is hardly surprising.

Of course, the devil is in the details. But so far, we don’t have many details and all the attention is on the submarine deal. For Australia, it has ended the agreement with France on diesel-powered submarines in favour of an agreement with the US on nuclear-powered submarines, something the previous government under Turnbull explicitly ruled out.

According to Hugh White:

If Australia’s submarines were intended primarily to defend Australia and our closer neighbours, then there is no way we’d consider nuclear propulsion. But the navy decided many years ago that the primary role for our new boats should be to operate off the coast of China in co-operation with the US Navy, and the government has eagerly gone along.

So the decision was made years ago that the defence of Australia is not just about the defence of the “homeland”, but include operating in China’s coastal waters. This is not a stretch since Australia has gone to wars in the Middle East — far away from the homeland.

Someone to balance and blame

Since the AUKUS announcement, many analysts have started looking for a “proximate cause”. Some say that China has only itself to blame, due to its coercion of Australia. However, even if China did not stop buying certain goods from Australia, the national security analysts in Australia who are supportive now are unlikely to change their position.

A common argument for AUKUS is that it is responding to China’s increasing power and restoring the balance of power in the region.

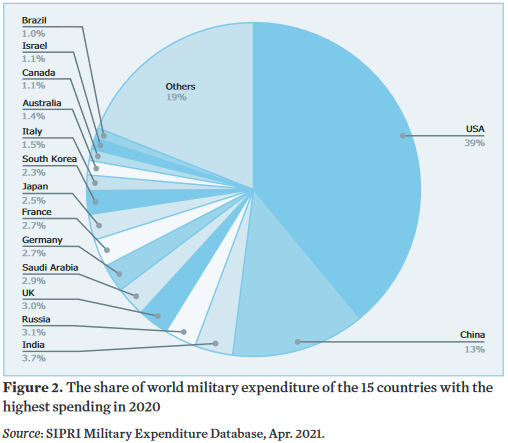

There is no doubt China is increasing its defence spending and is undergoing military modernization. However, as a percentage of GDP, its military spending has been steady at 1.7 per cent for the past ten years, according to SIPRI. Military spending is often expressed as a percentage of GDP (for example, Australia has committed to spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence) because we expect that as a country becomes richer, it spends more on defence.

Since power is relative, whenever the second most powerful country becomes more powerful, it necessarily threatens the existing top power. In that sense, it is China that is the “disturber” of the balance of power in the region. But it is a necessary characteristic of a rising power.

So when people say they want a “balance of power” or “responding to China”, what they really mean is restoring to the old power structure where the US is the dominant power — that is, no country in the world should rise and challenge the US.

After all, the US feels necessary to “respond to China”, even though it is currently spending three times as much as China on defence.

As Van Jackson observed on “balance of power”:

Every US national security strategy since Reagan has made reference to the balance of power, and always in a manner that endorses playing balance-of-power geopolitics but that invariably seeks to achieve a favorable imbalance of power.

Wolf warriors with French characteristics

France is understandably upset about the whole thing. Merely three weeks ago (!!), the inaugural Australia-France 2+2 Ministerial Consultations was held, where the ministers from both countries underlined the importance of the Future Submarine program. Australia has been active in encouraging France to do more in the Indo-Pacific. But apparently, Australia and the UK/US were negotiating behind France’s back this whole time!

France deployed its own version of “wolf warrior diplomacy”. It recalled its ambassadors from Australia and the US (China has not recalled its ambassador to Australia despite everything so far).

The French Foreign Minister called this “a stab in the back” and a betrayal of trust by Australia. To the UK, he reserved the colourful phrase “fifth wheel on the carriage”. The French Minister for European Affairs called it “a form of accepted vassalization”. Some French politicians even called it a “public humiliation”.

Hell hath no fury like a country scorned. No doubt just like the Chinese wolf warriors, many of these comments has a domestic audience in mind.

But Australian commentators and the Australian government are standing firm in the face of French “coercion” of Australia’s sovereign decision — many are telling France to get over it — ironic if you remember the Australian Prime Minister’s reaction to a single tweet.

Anyway, as I pointed out last week, business is business when it comes to economic and commercial interests, and that includes defence contracts. Do not assume anything can stand between a country and a bucket of money, not even an alliance.

We are happy little spokes

And that’s what makes the term “forever partnership” (by the Australian PM) cringeworthy. How can partnerships be “forever” when the geopolitical landscape is shifting and even interests are changing? At one point in time, China was the ally and Japan was the enemy.

AUKUS highlighted that Australia is doubling down on Anglosphere cooperation. It is bound even more tightly to the US, at the cost of building broader and deeper relationships with countries in the region. More hub-and-spoke and less multilateralism.

Australia is again seeking security from Asia, rather than security in Asia.

To do that, it is even sacrificing its “sovereign capability” — although I would argue that was never a realistic goal to begin with.

AUKUS is not designed for the current challenges faced by Australia. Australia’s biggest difficulty right now with China is in trade and economics, and not security. China is going to continue its “greyzone” activities against countries rather than warfare for the foreseeable future. AUKUS is unlikely to deter China from continuing its economic coercion.

Above all, I’m most concerned about the lack of transparency and public discussion before the deal is sealed. Even though it could have potentially wide-ranging implications, from nuclear policy to industry policy, it was presented to the Australian public as a fait accompli.

2. CPTPP

In the same week, in a strange twist, China has applied to join the CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership). China has been signalling its consideration to join this year, including most recently with a submission to Australia’s parliamentary inquiry into expanding membership of the CPTPP.

The precursor to the CPTPP was the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was driven by the US. It was originally envisaged as a way to mitigate the economic power of China in the region. The then US Secretary of Defense even called the trade agreement as important as another aircraft carrier. Yet after Trump was elected, the US withdrew from the agreement and the remaining countries had to negotiate a new agreement, the CPTPP.

While Biden has set a renewed focus on alliances, partners, and multilateralism, the US has not signalled its willingness to join the CPTPP. The protectionist sentiment has not shifted in the US under Biden. But ironically, China has applied to join.

We should rightly be sceptical about China’s application. Unlike Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, CPTPP is a “high-quality” and ambitious trade agreement. It deals not just with tariffs, but also behind the border barriers. Yet, China is tightening government control over aspects of the economy rather than liberalising, this would make joining CPTPP difficult.

Despite this, if China can demonstrate that it can reach the ambition of the trade agreement, then countries should support its application. But countries should also ask China about its use of trade for geopolitical purposes as part of the accession process.

3. Sexual assault cases

A Beijing court has dismissed the landmark sexual assault case, which was brought by Xianzi 弦子 (real name Zhou Xiaoxuan) against the famous CCTV host Zhu Jun 朱军, citing insufficient evidence.

According to Xianzi, her legal team met many “unreasonable difficulties”, including denial of requests for evidence collection. The court ruling is certainly a disappointment for Xianzi’s supporters and MeToo activists.

Authorities are clearly worried about the social ramifications of the ruling. According to China Digital Time, censorship instructions have been issued to internet companies to censor reports on the lawsuit.

There are high barriers for victims of sexual assault seeking justice in the court system. Earlier this month, the case against an Alibaba manager was also dropped. The court found that the man had committed “forcible indecency” but that did not constitute a crime.

Many people in China are paying close attention to issues on gender inequality and sexual harassment. The feminist movement is gaining popularity and broad-based support. However, it is still difficult for victims of sexual assault to find justice through the legal system. In addition, the popular support for MeToo and the potential for mobilisation is also perceived as a threat to the patriarchal CCP regime.

4. Electoral interference

Christian Porter was the Attorney-General of Australia, a portfolio with responsibility for Australia’s national security. In March this year, he was moved to another cabinet (senior ministerial) position as he was taking personal legal action against the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. This week, it emerged that he accepted anonymous donations via a blind trust to pay for his legal bills. Under pressure, he resigned from the cabinet but remained in parliament.

So what does that have to do with China?

Remember back in 2014 and 2015, Sam Dastyari, a senator who was not a minister, received payments from Chinese companies to pay his legal and travel bills. While he declared those payments appropriately, it still led to accusations of foreign interference and it led to him resigning from parliament in disgrace. The whole episode set off the Australian government passing the foreign interference legislation. However, interestingly, the payments received by Dastyari would not be illegal under the new legislation anyway.

According to David Speers:

Just days after Dastyari announced his resignation from Parliament, the newly minted Attorney General Christian Porter announced a ban on foreign political donations. He said it would “improve Australia’s confidence in the political system and prevent… new ways of soft power and influence through money.”

Now Christian Porter has accepted payments from unknown sources, but it would be easy for him to find out if he wants to. Yet the government appears to not be concerned about foreign interference risks at all — it is not forcing him to resign from parliament or even to disclose donors. Previously, the same government has been very vocal about foreign interference risks, especially in universities.

So it seems that the government is only concerned about foreign interference when it is convenient (such as when it targets the opposition or when it targets the sector it does not like).

Yet most of the national security commentators are also muted on this serious risk to Australia’s democracy and national security, in contrast to the outrage directed at Dastyari previously.

It makes me wonder whether the government and much of the national security community actually take “defending democracy” and “electoral interference” seriously. Or is it only a problem when we can connect it to China?

5. Military diplomacy

According to an upcoming book by reporters Bob Woodward and Robert Costa, the US chairman of the joint chiefs of staff Mark Milley reassured his Chinese counterparts about US government intentions.

US senator Marco Rubio has called Milley’s actions “treasonous leak of classified information”. But the former chair of the joint chiefs of staff Michael Mullen defended Milley’s actions, saying they were not abnormal, “having communications with counterparts around the world is routine”.

It is when tensions are at the highest and the relationships are at the most difficult that we can truly appreciate the value of diplomacy. Now we can comfortably examine whether Milley’s actions were right or not because war is not imminent. Looking back at the nuclear close calls between the USSR and the US, I’m thankful for the efforts of individuals to prevent a nuclear war.

Such diplomatic assurance actually shows the flexibility of US diplomacy. In contrast, as Peter Martin pointed out in his book China’s Civilian Army: The Making of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy, Chinese diplomats do not enjoy the same flexibility. They often deliver the same message regardless of the intended audience. The outcome of such diplomacy is surely less ideal.

However, if Milley’s concerns are correct, the most worrying aspect of it all is perhaps the potential for spillover of an unstable presidency and the perception by the US’s adversary that a US president could wage a war in order to stay in power.