- ‘🌈,’ I message my friend, who is an LGBTQI+ activist in China, on WeChat.

- ‘I’ll be there in a minute!’, she answers to let me know that she is online and available to connect to a VPN and talk to me via an encrypted platform.

A clever code of rainbows and secret words that avoid online censorship is a must for talking to my LGBTQI+ activist friends in China these days. While a dictionary of this language does not exist and it is constantly changing, fluency in double-speak allows queer 酷儿 communities to communicate without directly mentioning ‘politically sensitive’ and increasingly banned phrases like ‘gender and sexual diversity’ or ‘LGBTQI’. Just like when Chinese feminists replaced the censored #MeToo hashtag with the homophonous #MiTu/米兔 which was then translated as #RiceBunny, double-speak helps LGBTQI+ people avoid direct censorship online.

Queer Activism on the Field

The majority of my own LGBTQI+ activism in China occurred between 2014 and 2017 when I contributed to establishing Diversity — a formally registered LGBTQI+ student society in a sino-foreign University of Nottingham Ningbo China. Over a period of three years, we ran workshops within the University, created a student support group, and engaged with staff and students through social awareness raising activities, such as celebrating the International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia. Although Xi Jinping had been leader of China’s Party-State since 2012, many of his most restrictive policies had not yet been rolled out during that time. Living in a second-tier city with a relatively relaxed political atmosphere, our activities were only directly targeted once, when we planned to host a national gathering with twenty attendees to support the trans community. A volunteer loosely connected to our student group told us they were called by a police officer, who mumbled:

‘What… erm… do you know about this event that is set to happen over the weekend?’

‘I’m not a part of it, I’m not really sure what’s happening,’ they responded. Having inquired about the event, the police officer must have felt that his duty was complete and did not directly approach us.

It did, however, give us a big scare. While being invited to ‘drink tea’ 喝茶 — a euphemism for being asked to speak with police about something — is in some ways a badge of activist honour, the police interest prompted everyone to move their conversations to an encrypted platform and change venues. It was the sort of vaguely threatening encounter more common in first-tier cities that are political centres. Despite that isolated incident, those years were overall a flourishing time of community-building and raising awareness about LGBTQI+ issues in society.

Shrinking Digital Space under Xi Jinping

The current censorship landscape is dire: In July 2022 University administration at the top Tsinghua University in Beijing issued penalties to two students for placing handheld rainbow flags at an on-campus supermarket with notes encouraging passers-by to take them and celebrate #PRIDE. ‘Raising awareness’ 社会意识 is now a key term on the list for censorship. National legislation that is not LGBTQI+ friendly, such as the ‘sissy ban’ of 2021 that prohibited effeminate presentations of men on visual media, adds insult to injury. LGBTQI+ activists speculate that the goal of increased coercive control of LGBTQI+ communities and individuals through media, universities, and legislation is to silo queer individuals. If authorities discover evidence of my friends’ conversations with me, a researcher in a university outside of China, they will become a target of surveillance. Similarly, conversations among themselves about an LGBTQI+ group event or gathering is likely to draw attention from the ever-vigilant police, who monitor the digital communications of targeted groups and individuals as a matter of course.

The surveillance and censorship of LGBTQI+ activist and advocate groups is most intense in the Chinese digital space. For example, WeChat, the ‘everything app’ of China, is known to be a direct window for public security agencies to observe the activities of both informal LGBTQI+ groups and registered organisations. These agencies even use the collected data to map organisational relationships between activists, according to my recent research. No conversation on the app can be presumed to be private – a fact about which no repressed group can afford to be unaware.

In their recent book on China’s surveillance state, Josh Chin and Liza Lin unpack how surveillance on WeChat works in practice. The authors note that WeChat’s parent company Tencent ‘has vehemently denied suggestions that it gives police unfettered access to WeChat’s treasure trove of behavioural data’ [1]. However, numerous ‘coincidences’ that Chin and Lin uncover in the book suggest otherwise: for instance, in 2017, Hu Jia 胡佳, a civil rights activist and advocate for HIV-positive individuals, got a phone call from a state security agent who asked why he had bought a slingshot online using WeChat Pay the day before. Dr Li Wenliang, the COVID-19 whistleblower, had similarly been investigated on account of messages sent via WeChat to a private group of other medical practitioners to raise alarm over early signs that a highly infectious coronavirus was going around.

Other social media apps run by Chinese companies, including Weibo or Douban, are also required to monitor for ‘sensitive terms’ that entail censoring and cooperation with government authorities in other ways as well. In some cases, user accounts that are targeted by government agencies may also undergo ‘account bombing’, a practice where the authorities simply ‘bomb’ 炸号, or freeze, social media accounts which they consider sensitive for whatever reason at the time. Another covert means of online censorship is ‘shadow banning’—by which the authorities allow social media users to see their own posts while making them invisible to others. While significantly less harrowing than direct police harassment, such practices can seriously hamper online discourse.

My recent research suggests that, as early as 2020, COVID-19 became an excuse to justify extensive surveillance and police monitoring beyond subjects directly related to the pandemic itself. As many cities were sent into lockdown beginning in 2020 with Wuhan hitting the record with 76 days, LGBTQI+ communities – like many others – shifted their activities to the digital space. At the same time, the digital space allowed to LGBTQI+ communities started shrinking. Moving activities online also meant they became more susceptible to monitoring. Many activists I spoke to reported being repeatedly rung up and even threatened by police because of their online activity.

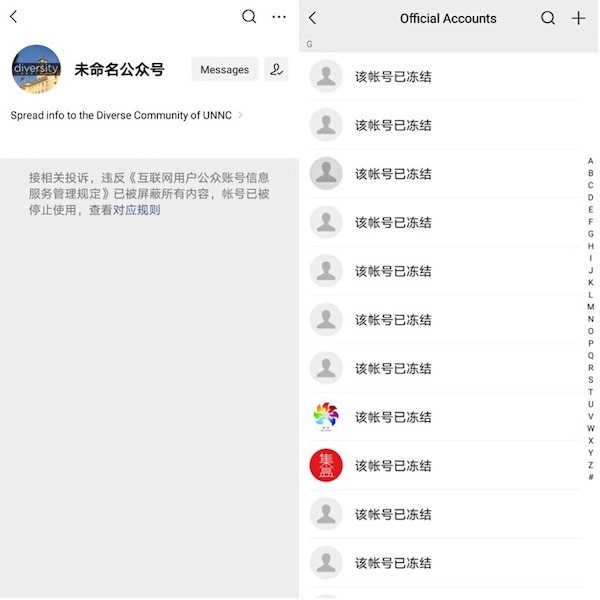

LGBTQI+ conversations on WeChat have been heavily restricted since July 2021 when hundreds of student-run LGBTQI+ public accounts on WeChat were shuttered overnight and replaced with a vague message:

In response to relevant complaints, all content has been blocked for violating the ‘Regulations on the Management of Internet User Official Account Information Services’, and the account has been suspended.

July 2021 was the end of relatively free online communication among the LGBTQI+ communities in China, which had been able to share queer content online. From then onwards, each LGBTQI+ group or individual posting about LGBTQI+ issues online could expect to be targeted for police monitoring and censorship. The situation is similar on Weibo, an online microblogging platform run by Sina. While LGBTQI+ groups in different geographic locations face unequal amounts of intrusive censorship and police attention, most agree that civil society under Xi Jinping’s leadership is extremely restrictive, unlike in the relatively tolerant times under the previous leader Hu Jintao.

Author’s screenshots showing the long list of LGBTQI+ WeChat official accounts that were closed overnight in July 2021. First published in the Interpreter.

Queer Double-speak

Developing double-speak, a set of linguistic codes and emojis that express meaning without triggering censorship, is now a crucial part of the queer activism and advocacy landscape. It plays two key functions of helping to dodge automated censorship against suspected banned keyword lists and re-appropriating language to protect LGBTQI+ community organising. Instead of an ‘awareness raising’ activity, it may be a call for a gathering of friends. An opaque rainbow background on an event poster, technically more difficult for censors to pick up than text, is a sufficient signal that a forthcoming event invites the LGBTQI+ community.

The practice of re-appropriated language to create queer double-speak is an established tradition. The word tongzhi 同志 (comrade), re-appropriated from Communist lingo by the queer community, is perhaps the most salient example. It was an approved form of address with a history dating back to 1950s when personally mandated by Mao Zedong and had been used widely up through the early reform period even to address waitstaff or salespeople. The term was first used at the Gay and Lesbian Film Festival in Hong Kong in 1989 and was quickly adopted by the LGBTQI+ community in mainland China. Because it was also the correct term by which fellow party members addressed one another, the it could not be easily censored. For example, in 2001, Peking University students organised a queer film festival that they named ‘the first Chinese Tongzhi Cultural Festival’; not familiar with the double-speak, the Youth League of the University approved the event, which went on for a couple of days before it was shut down by University authorities.

A queer double-speak dictionary is unlikely to be made available to the public anytime soon. Such attempt might risk placing a direct spotlight on words used to avoid online censorship, and if placed in the wrong hands, can be used as an actual censorship dictionary. Moreover, LGBTQI+ double-speak is fluidly moving with the needs of the community, emerging organically and spontaneously. As new political and social pressures develop under Xi Jinping’s leadership, new terms of queer double-speak are sure to emerge in the future.

Despite the fact that some groups avoid the risks of the online world altogether and rely on (offline) word of mouth to share information, including about events; LGBTQI+ communities are surviving — if not thriving — in the digital space under the current political climate. Queerness is not something that can be suppressed, including by censorship, and resistance inevitably follows control and surveillance. A practice with historical roots when sexual and gender diversity was outlawed, double-speak is an important strategy for self-preservation of LGBTQI+ individuals, and to preserve their digitally connected communities. As one of LGBTQI+ activists and advocates put it in conversation with me, ‘even if lotus seeds are dormant for a hundred years, they will bloom when the conditions improve.’

References

[1] Josh Chin and Liza Lin, Surveillance State: Inside China’s Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2022, p.111.