With 281 languages from nine language families,[1] China has a high degree of linguistic diversity. The distribution of speakers of these languages is greatly uneven. Of a total population of more than 1.4 billion, 91.11 percent are Han Chinese and speak Putonghua and/or other Sinitic languages;[2] the remaining 8.89 percent of the population, the non-Han Chinese or minority ethnic groups, speak 200 other languages. The south-west shows the greatest linguistic diversity in the nation. Yunnan province is outstanding for the number of languages from different language families, as shown in figure 1. This article explores language use and dominance in Yunnan’s Heqing county.

Figure 1: Snapshot of languages spoken in Yunnan province and the neighbouring area. Each dot represents a language, and the dots of the same colour and shape indicate languages from the same language family. Data source: Harald Hammarström, Robert Forkel, Martin Haspelmath and Sebastian Bank, Glottolog 5.0, Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, 2024, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10804357 (available online at http://glottolog.org; retrieved 3 September 2014)

It is common for people in a region with a high degree of linguistic diversity to learn and speak different languages through social and cultural activities, such as formal schooling, interactions with friends who speak another language, and expressing opinions at official events. The patterns of multilingualism – that is, how a person uses two or more languages in different situations – vary across different communities.

For example, in northern Vanuatu, due to common intergroup marriages, intense trading networks, and ritual and cultural events, children grow up learning two or more languages.[3] None of these languages is socially or politically dominant so linguists call this a pattern of egalitarian multilingualism. In contrast, what can be observed in Yunnan nowadays is a pattern of hierarchical multilingualism in which languages are ordered according to their dominance in different domains of life: Standard Chinese (the term refers to both the spoken and written language as opposed to Putonghua, the official spoken language) as the official language over a local major language over one or a set of minority languages.

The predominant status of Standard Chinese in Yunnan and across China is a result of decades of efforts in promoting it as a national language and other linguistic policies. Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the government has promulgated a series of policies such as using simplified characters 简体字 for writing, the promotion of Hanyu Pinyin 汉语拼音 as a system for teaching standard pronunciation, and the promotion of Putonghua 普通话 as the national spoken language to deal with the challenges of significant linguistic diversity. These challenges included intergroup communication and widespread illiteracy,[4] which have a long history in China. Putonghua is promoted as the lingua franca and used in almost all the official domains, including education, government administration and broadcasting.

The status of minority languages is also closely related to language policies. Unlike in some other provinces, the non-Sinitic languages spoken in Yunnan do not enjoy a prominent official status. This is despite the fact that China’s constitution recognises and protects the right of all nationalities to use their spoken and written language. Students of Korean nationalities in Yanbian 延边, Jilin province, for example, can choose to take the national college entrance exam 高考 in Korean rather than Chinese. However, in Yunnan province, the option for minority nationalities 少数民族 to take the exam in their own languages does not exist. Non-Han people in Yunnan do not have a chance to study their mother tongues formally, and everyone needs to study Standard Chinese at school. None of the minority groups (groups whose languages are not mutually intelligible) in Yunnan, however,[5] have any linguistic advantages over others in the college entrance exam.[6]

With Standard Chinese in the predominant position, it seems the minority languages in Yunnan are lumped together in an equal position – unless we look beyond official domains such as education and governmental administration. The situation at the community level is complex. The hierarchy of languages at the community level depends on whether there is one large minority language used in the region in addition to Standard Chinese and how different groups communicate with each other. I will explain how this works on the basis of my field experience working with Kua’nsi people in Yunnan.

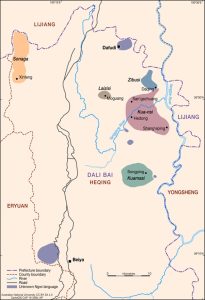

There are approximately 5,000 Kua’nsi people in Liuhe Yizu township 六合彝族乡, which is in Heqing county 鹤庆县 in the Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture 大理白族自治州 of Yunnan. Kua’nsi people are recognised as part of the Yi nationality 彝族. However, their language is not mutually intelligible with the languages spoken by other Yi groups. Kua’nsi people do not consider themselves the same as other Yi groups. They refer to themselves as the ‘Kua’nsi subgroup of Yi nationality’ 彝族夸恩斯支系. Although Standard Chinese is the primary language used in education, governmental administration and other official domains, Kua’nsi remains the primary language of communication between Kua’nsi people in their villages, which are mostly homogeneous. As there is no written mode of the Kua’nsi language, Kua’nsi people will write things down in Chinese. People who did not attend school for education rely on others to read and write Chinese.

In Heqing county, more than 98 percent of the population is Bai, and therefore the major language is the local variety of Bai language, Heqing Bai. Kua’nsi people have been in close contact with Bai 白族 and more recently with Han people as well. For communication with people from outside the villages, Kua’nsi people have learnt to speak – or at least understand – Heqing Bai and the local south-western variety of Mandarin Chinese. The use of the latter is also expanding within the villages. People who are Bai or Han rarely learn Kua’nsi to fit in. I know only one Bai man who married into the village and learnt Kua’nsi.

Patterns of multilingualism have started to shift within the Kuai’nsi community. Men from older generations are likely to be bilingual in Kua’nsi and Heqing Bai, or even trilingual in these two languages and the local variety of south-western Mandarin Chinese, while women of these generations are more likely to be monolingual in Kua’nsi but sometimes have some knowledge of Bai. Younger people tend to speak both Kua’nsi and Putonghua. Some of them might have some knowledge of Heqing Bai. Although bilingualism is common, it is by no means the case that every Kua’nsi can understand Heqing Bai or Mandarin. There is still a need for interpreters, especially between elderly Kua’nsi and outsiders.

Figure 4: The author (left) and two Kua’nsi women, Jiao Xiangxiu (middle) and Jiao Feiying, discussing the language structure of Kua’nsi.

The change in the pattern of bilingualism is due to the promotion of Standard Chinese in official domains, especially through education. Each administrative village has one primary school, where Kua’nsi children start to learn Standard Chinese formally. Classroom instructions in Kua’nsi may be available for students in the first and second years of primary school to help them transition to understanding and speaking Putonghua properly, but this depends on whether the teacher is also Kua’nsi. In most cases, the teachers are not Kua’nsi but are from different ethnic backgrounds, such as Bai, Han, Naxi and other ethnic nationalities in the region, so the students are encouraged to speak Putonghua from their first year of primary school. In the primary school where I conducted fieldwork, teachers would tell the students that they must speak Putonghua in school even with their Kua’nsi peers. Teachers also mentioned to me that some students were struggling to compose Chinese sentences properly, seemingly the result of students using Kua’nsi language structure and word order to write sentences in Chinese. Thus the lack of a mother tongue in formal education not only reduces the chances of the language used in private and official contexts but also poses a challenge for students whose first language is not Standard Chinese to achieve better academic performance.

The divide in the multilingual hierarchy is not just between Standard Chinese and the minority Kua’nsi language. Often, there is tension between another relatively larger minority language and a smaller one. Before Standard Chinese gained predominance in the region, Heqing Bai was the lingua franca for different ethnic groups in the region. As a result of the long history of contact, Kua’nsi people use many borrowed words from Heqing Bai. For example, they call boiled water xwa33si33, which came from Heqing Bai. Although nowadays Heqing Bai is becoming less dominant compared to Standard Chinese, Kua’nsi children still pick up words and phrases from Heqing Bai, the language of their friends and teachers, when they go to Liuhe township for middle school and Heqing county for high school. People whose first language is Heqing Bai, by contrast, had little motivation for learning Kua’nsi language.

This sometimes leads to discrimination. As one former student mentioned to me, some Kua’nsi kids were mocked for their language at school. He remembered that his English teacher once asked him why he could not speak English properly as his mother tongue already sounded like a foreign language. The comment from this teacher reflects the ignorance of local non-Kua’nsi people towards Kua’nsi and how Kua’nsi people sometimes are considered exotic to them.

Hierarchical multilingualism in Yunnan highlights the broader dilemma for people of minority groups in China who must learn not just Standard Chinese but also the languages of other more dominant groups to improve their life. As the minority group in the region, Kua’nsi people need to know how to speak both Heqing Bai and Chinese (Putonghua or local south-western Mandarin Chinese) to communicate with government officials, to bargain in the market and to trade with outsiders. Hence, being a smaller minority group in the region not only means they need to learn Standard Chinese for better education but also puts them in a less equal position in many political, social and economic activities, compared to the larger minority group who can use their language in more situations. During the Targeted Poverty Alleviation campaign 精准扶贫 in Kua’nsi villages, the Heqing local government sent officials there to teach the villagers how to plant cash crops to raise their annual income. These officials are mainly of Bai nationality and do not know any of the Kua’nsi language, so the villagers were helpless without an interpreter, usually the village leader. In this situation, Putonghua is the main language of communication: the village leader would translate the government officials’ speech from Putonghua into Kua’nsi and the villagers’ speech from Kua’nsi into Putonghua. If the villagers were Bai or if the officials had put effort into learning the Kua’nsi language, the conversation between the government officials and the villagers would be more direct and efficient.

A majority within a minority

Despite having a population of only 5,000 people in Heqing, Kua’nsi enjoys a more advantageous position compared with some even smaller minority groups. In addition to Kua’nsi, there are four other Yi groups in Heqing: Kuamasi, Laizisi, Zibusi and Sonaga, with populations ranging from a few hundred to just over a thousand.[7] Although they are all considered minority groups in Heqing, they do not receive equal amounts of attention or resources from the local government.

Government projects for the revitalisation of local cultures in Heqing have focused on the dominant Heqing Bai, yet the culture, language and history of the Kua’nsi have received more attention from the local government and scholars than those of the four other Yi groups. For example, the local government sponsored the publication of an edited volume on the society, history and culture of the Kua’nsi community.[8] My PhD project is also a language documentation and description project that contributes to the preservation of the language and culture of Kua’nsi people.[9] Kua’nsi culture has also been branded as a tourist attraction, while the four other groups have not received similar recognition. It is well known in the region that Kua’nsi people wear their traditional clothes made from fire grass, and the local government recently organised a workshop to teach young Kua’nsi women to make traditional clothes as a means of cultural preservation. Those four other Yi groups ceased to wear traditional garb from the 1970s, let alone had a workshop to learn how to make them.[10] People in some villages even shifted to wearing the clothes of Heqing Bai.

The lack of government recognition due to hierarchical multilingualism threatens the preservation of minority cultures and languages. The languages of all these smaller Yi groups in Heqing county are in danger of extinction.[11] At least Kua’nsi language and culture are being documented and could be revitalised; the others will be seriously endangered if no action is taken soon.

Conclusion

The story of language use in China is not as simple as Standard Chinese versus all other languages and dialects. It must also take into account the double or multiple divides between Standard Chinese, other Sinitic languages and dialects, as well as larger minority languages and smaller minority languages according to the dynamics between languages in a particular region. The recognition of hierarchical multilingualism and its influence on minority groups illuminates the challenges faced by minority groups in contemporary Chinese society.

In addition to sponsoring research projects on documenting minority languages in China, the Ministry of Education and State Language Commission jointly launched the China Language Resources Protection Project 中国语言资源保护工程 in 2015.[12] This is a welcome effort to protect and understand languages and dialects in China. It is also important to transfer the knowledge from research to community language preservation projects, so that minority languages can be kept alive and passed on to future generations.

Notes

[1] The data on languages spoken in China is from https://www.ethnologue.com/country/CN/#typology. Language family is the linguistic classification of languages that are genetically related and languages of the same language family developed from a single ancestral language. Languages spoken in China are from these language families: Sino-Tibetan, Kra-Dai, Hmong-Mien, Austro-Asiatic, Mongolic, Turkic, Tungusic, Austronesian and Indo-European as well as a couple of unclassified languages.

[2] National Bureau of Statistics, ‘Main data of the seventh national population census’ 第七次全国人口普查主要数据情况, 11 May 2021, online at: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1901080.html. The distinction between language and dialect is not always clear and easy to draw. From a purely linguistic perspective, the difference between language and dialect is the degree of mutual intelligibility; for example the degree to which a person can understand the language spoken by another person. In the context of China, the distinction is made between the official language and other speech varieties. Putonghua is considered the only standard language of modern Chinese, and all other speech varieties of Chinese are dialects of this language; that is, Pǔtōnghuà 普通话 ‘common speech’ as the standard language versus other Sinitic languages/varieties as fāngyán 方言 ‘dialect’, although many of them are not mutually intelligible; for example Cantonese versus Shanghainese; the great differences between varieties of Mandarin in northern and south-western China. In this article, the term ‘Sinitic languages’ is used as an umbrella term. and it refers to all the speech varieties that are spoken by Han people.

[3] Alexandre François, ‘Social ecology and language history in the northern Vanuatu linkage: A tale of divergence and convergence’, Journal of Historical Linguistics, vol. 1, no. 2 (2011): 175–246.

[4] Bernard Spolsky, ‘Language management in the People’s Republic of China’, Language, vol. 90, no. 4 (2014): e165–e179.

[5] The term ‘minority group’ is not the same as少数民族 in this article. This aims to differentiate groups whose languages are not mutually intelligible within one minority nationality. Again, the division is made on purely linguistic grounds. During the recognition of nationality status (民族识别工作) from the 1950s to the late 1970s, the government recognised 55 nationalities out of 400 applications (Minglang Zhou, Multilingualism in China: The Politics of Writing Reforms for Minority Languages 1949–2002, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2003, p. 8). Small groups that are closely related to each other were lumped together, although their languages are not mutually intelligible. For example, the Yi nationality 彝族is a large nationality, but it is not a homogenous one. It contains Yi groups whose languages and cultures are quite different from each other, although related. The Yi nationality includes Yi groups like Nuosu 诺苏, Niesu 聂苏, Lalo腊罗, Kua’nsi 夸恩斯, Khatsuo 卡卓, Talu 他留 and many others. Although these groups are historically related, they do not consider themselves the same as each other. These groups are also related to Lahu拉祜, Lisu 傈僳 and Hani哈尼, which are recognised as separate minority nationalities in China.

[6] ‘One way China has tried to solve the problem of minority children not understanding Chinese is to translate language textbooks. Yunnan province, in particular, has translated the national Chinese language textbooks for first and second graders into 14 different languages. These textbooks have the Chinese and the minority language side-by-side and are used mainly as diglots [i.e. bilingual books]. The focus is on having the minority language as an aid to help the children understand the Chinese texts.’ From Heidi Cobby, ‘Challenges and prospects of minority bilingual education in China: An Analysis of four projects’, in Anwei Feng (ed.), Bilingual Education in China: Practices, Policies and Concepts, Clevedon/Buffalo/Toronto: Multilingual Matters, p. 188.

[7] Andy Castro, Brian Crook and Royce Flaming, ‘A sociolinguistic survey of Kua-nsi and related Yi varieties in Heqing county, Yunnan province, China’, Journal of Language Survey Reports, 1–96 (2010). SIL Electronic Survey Reports 2010–001. Online at: https://www.sil.org/resources/publications/entry/9202.

[8] Jinhe Gao, Jiao Xiongcai and Wang Hongzhi (eds), A Collection of Research on Heqing Baiyi Culture 鹤庆白依文化研究合集, Kunming: Yunnan Nationalities Publishing House, 2015.

[9] Huade Huang, ‘A grammar of Kua’nsi’, doctoral thesis, Canberra: Australian National University, 2024. Online at: http://hdl.handle.net/1885/316664

[10] Castro, Crook and Flaming, ‘A sociolinguistic survey of Kua-nsi and related Yi varieties in Heqing county, Yunnan province, China’, pp. 39–40.

[11] Many factors contribute to the endangerment of languages, such as reduction/shift in domains of language use, community members’ attitude towards language, governmental language policy, availability of literacy and educational materials and so on. (See the link for the discussion of these factors of language endangerment: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183699) A language is dying out when no children learn it as their mother tongue; that is, the intergenerational transmission stops (Nikolaus Himmelmann, ‘Language endangerment scenarios: A case study from northern central Sulawesi’, in M. Florey (ed.), Endangered Languages of Austronesia, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010, pp. 45–72), and it is dead when the last speaker dies.

[12] More details about the project can be found at https://zhongguoyuyan.cn/index