The rapid spread of COVID-19 around the world has heightened concerns about the unprecedented level of globalisation that characterises the world we live in – or lived in until 2020 began. In Australia, these concerns tend to focus on our ‘excessive reliance’ on China. Yet China’s vast economic resources and its government’s capacity to stimulate growth will work in Australia’s favour in the year ahead, suggesting that our ‘China problem’ may instead be a blessing in disguise.

As Chris Ulhman put it in March, “Two-thirds of the world’s economy now put China as one of their top three trading partners. That’s the real problem with this. We are deeply dependent on a single economy. Literally when China sneezes, the world catches a cold.” This phrase has never been more apt than it is in 2020. But is our deep dependence on China the ‘real problem’? The answer at this stage is a resounding no.

There is no question that Australia, “the world’s most China-reliant economy [is] reel[ing] from virus shockwaves”. China accounts for a third of our total exports, and significantly more in some sectors. A first quarter of negative GDP growth in China has inflicted substantial economic pain on vast swathes of the Australian economy, from fisheries, iron ore and LNG to higher education and tourism.

Diversification of our exports towards other emerging markets is often proffered as a solution to this ‘China problem’. India is heralded as a prime example, with its vast population and growth potential – even if that potential is far from being realised. Goldman Sachs has just downgraded its projections for Indian GDP growth in 2020 from 6% (in January) to a mere 1.6%. Its US and Euro projections are even more dire, at -6% and -9% respectively.

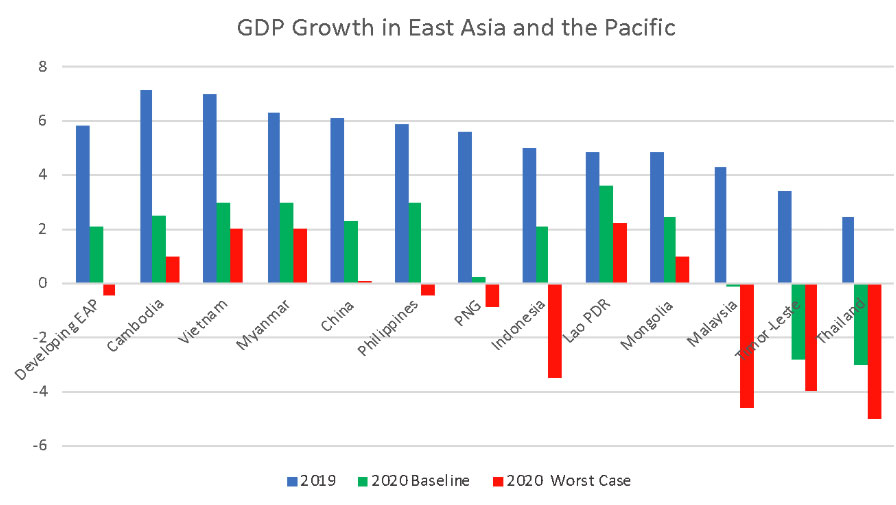

A World Bank report published on March 30 presents an equally distressing picture for East Asia and the Pacific. With regional growth projected to plummet from 5.8% in 2019 to 2.1% in 2020 in the baseline scenario (and to -0.5% in a worst-case scenario of a deep contraction and sluggish recovery), no country will be spared. And while that includes China, the size of its economy means that it will account for more regional (and global) output by the end of 2020, not less.

Sourced from World Bank, 30 March, East Asia and the Pacific in the case of COVID-19

To put these figures in perspective, with a US$13.6 trillion economy in 2019 and growth of 2.3% in 2020, China would increase its output by US$313 billion in 2020. Thailand and Malaysia, the second and third largest economies in the East Asia and Pacific region, are projected to contract, while the Philippines in fourth place, with slightly higher projected growth than China, will contribute just US$9.9 billion. India, with a 2019 GDP of US$2.73 trillion, will add US$43.6 billion – about one seventh of China’s contribution.

The Chinese government is highly unlikely to settle for growth of 2.3% in 2020, given its current official growth target of 5.6% (likely to be downgraded to 5% shortly). On top of the range of targeted measures already in place to restart the economy, expectations are rising that the Chinese government will soon introduce a fiscal stimulus package similar in scale to the one rolled out during the global financial crisis of 2007-08 (of $4 trillion yuan or US$575 million). As reported by Reuters in mid-March, this could include an infrastructure investment package backed by up to 2.8 trillion yuan (US$394 million) of special bonds issued by local governments. No other government in the region has this kind of capacity to stimulate economic growth.

China’s fiscal stimulus during the last financial crisis resulted in growth rates that were far above the rest of the world, officially reaching 9.7% in 2008, 9.4% in 2009, and 10.6% in 2010. This contrasted with the recessions in most of the developed world: of all OECD countries, only Poland, South Korea and Australia were spared.

Australia’s dependence on China at the time – alongside its own fiscal response to the crisis – had plenty to do with this outcome. Then, China’s stimulus was directed towards government-led projects in hard infrastructure, which resulted in high demand for Australian iron ore and other resources. The 2020 stimulus will instead support ‘new infrastructure’ including 5G networks, data centres, and charging stations for new energy vehicles. In a more direct response to the health crisis, there will also be new projects targeting public health and emergency materials supply. Australia might not stand to benefit so obviously from this kind of spending. But there will still be ample opportunities that Australian companies can tap into.

None of this is to deny the substantial risks that remain for China, including a possible surge in new infections (which would in turn lead to new lockdowns), alongside heavily damaged investor and consumer confidence and plummeting global demand. But it does suggest that China is likely to be the most significant source of renewed demand for Australian exports.

The rock lobster, or ‘Dragon Shrimp’ as it is known in Chinese, is a symbolic case in point. While a Bloomberg article published on 27 February described the decimation of Chinese demand for this ‘prized’ Australian export’, an Australian Financial Review article published on April 9 declared that demand is bouncing back ‘just in time for Australia’s struggling fishermen’. There is simply no other country in the world that could put ‘lobster back on the menu’ and save an Australian industry in this way.

The Australian government’s economic response to the coronavirus is both promising and welcome, with total support of $320 billion (16.4% of annual GDP) already on the table. But without China’s renewed demand for Australian goods and services, this won’t translate into significantly higher growth for the Australian economy in the months, and years, ahead. Australia may well have caught this terrible ‘cold’ from China. But on the road to recovery, its relationship with this economic giant is likely to be its greatest strength – not its biggest problem.

An earlier version of this article was published by CEDA on April 14, 2020.