Many of us are familiar with the concept of cancel culture in the West. Merriam-Webster defines it as ‘the practice or tendency of engaging in mass cancelling as a way of expressing disapproval and exerting social pressure’. Though not without controversy, at the core of Western cancel culture is the desire of the general public to hold public figures accountable for their actions. It is driven by widespread public sentiment and implemented by individual entities (including companies which may, of their own accord, choose to terminate engagement with the person involved).

However, there is a growing culture of extreme celebrity cancellation within China, and the driving force is not always genuine social sentiment, but rather an increasingly competitive industry with monopolistic influence stretching across social media platforms, streaming and video sharing platforms, as well as state-run media outlets. Together they create a progressively hostile online environment flooded with misinformation and highly manipulated ‘public opinion’. This type of cancellation is implemented by the platforms themselves, often leading to near-total erasure of a person’s online existence within a matter of days.

The story of actor Zhang Zhehan

The year 2021 saw a string of high-profile celebrity cancellations, including actor Zhang Zhehan 张哲瀚, star of the popular danmei 耽美 (Boys’ Love) series Word of Honor. However, unlike other cancelled celebrities, such as pop star Kris Wu 吴亦凡 who was arrested on suspicion of rape, and actress Zheng Shuang 郑爽 who was fined for tax evasion, Zhang committed no crimes. In August that year, Zhang was cancelled over old vacation photos of cherry blossoms taken in the open park area of Japan’s Yasukuni Shrine, a popular tourist destination that, as recently as 21 March 2022, was still recommended by Chinese state media for cherry blossom viewing. One cherry tree in this park is used by Japan’s Meteorological Agency as a benchmark to determine the start of the annual cherry blossom season.

But for many Chinese, the Yasukuni Shrine remains controversial because it honours Japanese war criminals involved in World War Two atrocities, including the Nanjing massacre, which, according to official Chinese accounts, killed over 300,000 civilians and unarmed soldiers (though the actual death-toll remains a subject of controversy). Annual visits by Japanese Prime Ministers to pay respects at the shrine continues to elicit strong condemnation from the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and state media.

In 2002, it was reported that the actor Jiang Wen 姜文 had visited the Yasukuni Shrine to conduct research for his film Devils on the Doorstep 鬼子来了, set during the Sino-Japanese war. Although Jiang was quickly labelled ‘unpatriotic’ and ‘a traitor’, many prominent intellectuals, writers and directors came to his defense. ‘It is a sign of ignorance to simply equate visiting the Yasukuni Shrine by any Chinese citizen to an act of treason’ commented Guo Weitao 郭伟涛, a senior colonel of the Strategic Teaching and Research Office at the National Defense University. Bai Yansong 白岩松, a famous presenter at state-owned broadcaster CCTV, said, ‘Worshipping at the Yasukuni Shrine follows a strict and complicated procedure. Except for militarists, most people who visit the Yasukuni Shrine are not there to can bai 参拜 (worship or pay respect).’ Their comments not only show the nuance between visiting and worshipping at the shrine, but also the openness of the Chinese internet that allowed for such discussion twenty years ago.

In contrast, when Zhang Zhehan’s vacation photos surfaced online in August 2021, misinformation claiming he had visited or even worshipped at the controversial shrine circulated widely. Zhang denied these allegations and issued an apology for not knowing the significance of the buildings in the area where his photos was taken. Nonetheless, misinformation continued to spread, and Zhang, like Jiang Wen, was also accused of being ‘unpatriotic’ and a ‘traitor’. But Zhang’s incident happened during the age of viral social media and an online environment much more prone to toxicity. The few people who spoke up for him, including Tsinghua professor Yin Hong 尹鸿, were berated and saw their Weibo accounts muted or deleted. Zhang’s cancellation was swift: within a few days, his name, social media accounts, and all related contents (from dramas he acted in to fan-made content) were virtually erased from every Chinese streaming platform and social media site. In comparison, Jiang Wen’s movie, released in 2000, remains highly regarded, and his career was unaffected.

Who cancelled Zhang Zhehan?

Since Zhang’s cancellation, many of his fans have sought to clarify misinformation and call attention to injustices involved in the reporting and handling of Zhang’s case. The evidence even suggest that Zhang might have been the victim of a targeted smear campaign. His three-year-old vacation photos surfaced on 13 August, a sensitive date leading up to Victory Day on 15 August (the day Imperial Japan surrendered in World War Two), and most of the accusations against Zhang were easily debunked. However, this side of the story is noticeably absent from Chinese media coverage of Zhang’s cancellation. Furthermore, clarifications and rational discourse on this topic were systematically deleted from Chinese social media platforms. Fans had to move most of their clarifications to international platforms like YouTube, Twitter, and personal blogs (including my own) in the hopes of preserving and spreading the truth.

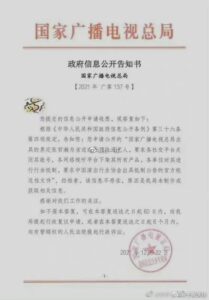

While it is easy to attribute this level of erasure to state-driven censorship, in Zhang’s case, the story is not so simple. To clarify whether the state was involved, his fans have sent multiple inquiries to the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MCT, 中华人民共和国文化和旅游部) and the National Radio and Television Association (NRTA, 国家广播电视总局), the two government bodies that oversee the entertainment industry. Their official responses denied that they had any hand in the cancellation of Zhang.

MCT denies asking platforms to take down Zhang’s works, close his accounts, erase positive content leaving only condemnation, take down fan work or related Weibo posts, or asking CAPA to initiate an industry boycott

NRTA denies classifying Zhang as a ‘problematic artist’, asking platforms to take down his works, initiating an industry boycott, or asking CAPA to initiate an industry boycott.

In fact, an organisation called the China Association of Performing Arts (CAPA, 中国演出行业协会) had issued the statement calling for an industry boycott against Zhang on 15 August 2021 (Victory Day), only two days after Zhang’s old photos began to circulate. In comparison, after Kris Wu was detained on 31 July 2021 over suspected rape, it took more than two weeks for CAPA to issue a boycott. Though CAPA has been around since 1988, it never attracted much public attention until Zhang’s case. It is not entirely clear the extent to which CAPA takes direction from the Party and state. It falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism but it does not take directives exclusively from the government and operates on its own initiative as well.

Three months later, CAPA released their ninth list of ‘immoral artists’ 劣迹艺人 with eighty-eight names on the list. Its prior ban lists only included livestreamers, but this one included three actors for the first time: Kris Wu, Zheng Shuang and Zhang Zhehan.

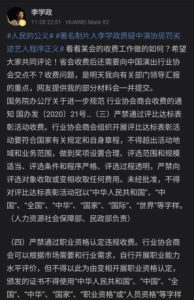

The inclusion of Zhang on CAPA’s ninth list of ‘immoral artists’ drew the attention of Li Xuezheng 李学政, the executive producer of the popular anti-corruption drama In the Name of the People 人民的名义 and the director of the Golden Shield Television Centre 金盾影视中心, a subsidiary of the Central Military Commission of the Communist Party of China. In a widely circulated video posted on Weibo, Li raised a series of questions regarding CAPA’s list of banned artists, including 1) the procedural fairness of CAPA’s ban; 2) the standard for judging ‘morality’; 3) the qualification of CAPA members who evaluate the moral standards of an artist; 4) the conditions and duration of an artist’s punishment; 5) the lack of any process for appeal.

CAPA’s boycott notice against Zhang, using the word ‘visit’ to describe Zhang’s presence at the shrine.

CAPA’s underhanded tactics and expansive connections

According to its website, CAPA ‘adheres to the purpose of serving members and the [entertainment] industry’, such as ‘carrying out industry self-discipline and industry research activities’. However, CAPA may be violating its own policies in its boycott against Zhang. In an interview with the state-run Xinhua News Agency on 6 February 2021, CAPA made clear that their charter of ‘self-discipline’ (punishment of bad artists) came into effect on 1 March 2021, and is not retroactive. Zhang’s photos were taken in 2018.

Li Xuezheng noting that organisations may not legally collect membership fees while masquerading as a government entity by using the word ‘中国’ (China) in its name.

In addition to breaching their own policies, Li Xuezheng pointed out that CAPA may be violating legal procedures as well. Although the organisation claims to be non-profit, CAPA charges exorbitant membership fees that vary between RMB 2000 to 10,000 per term. This may actually be illegal because, according to Li, organisations with the term ‘China’ in their names are presumed government entities and not legally allowed to collect membership fees. CAPA’s website provides an impressive list of member corporations, including big names like Huawei. Netizens noticed that you cannot use Zhang Zhehan as a nickname on Huawei phones, a needless inconvenience for Zhang and others who may share the same name.

In his posts, Li further exposed the influence CAPA exerts over official media agencies. Within minutes after CAPA published their 9th list of banned artists on 23 November 2021, many official media accounts shared it on Weibo and other social media platforms, creating the impression that the ban enjoyed broad public and official support. In contrast, an article originally published by an account affiliated with the MCT that presents a negative public perception of CAPA, went unnoticed for over a month, before Li brought attention to it.

To understand how an organisation like CAPA can exert such influence, it is worth noting that public opinion in China can be purchased for the right price by anyone or any agency. Many accounts on China’s social media sites, including personal user accounts and marketing accounts, can be bought. A netizen found that a specific bundle of 388 accounts, for example, could be bought for the bargain price of 3,888 yuan. Even Weibo ‘hotsearches’ 热搜, which are the equivalent to trending hashtags on Twitter, can be bought at an affordable price. In addition, engagement can be further promoted using ‘water armies’ 水军, or human bots that can flood the internet with content they are paid to promote. With this array of payable marketing services, anyone with enough money can manipulate public opinion in their favor.

Since Li began his public campaign against CAPA, the organisation has never directly responded to Li’s questions, but it has been caught employing many underhanded tactics against Li, unwittingly revealing the depth of influence CAPA exerts over Chinese media and social media platforms.

Countering the concerns and criticisms raised by Li Xuezheng and others, Xinhua, China’s official news agency, published an interview with a CAPA representative on 1 December supporting CAPA’s ninth list of ‘immoral artists’. Internet sleuths quickly discovered that the author of that article, Bai Ying 白瀛, is actually a member of CAPA’s ethics committee, prompting criticisms that CAPA had interviewed itself for the Xinhua piece. Further digging revealed that the Chinese Communist Youth League 共青团中央, which published one of the first damning articles in August using the word ‘worship’ to describe Zhang’s cherry blossom photos (implying Zhang deliberately went to pay respects to Japanese war criminals), is also listed as part of CAPA’s ethics committee.

In addition to state media, an article published on 11 September 2021 includes a list of companies that support CAPA’s industry self-discipline initiatives, highlighting the broad influence CAPA held over social media platforms. It includes almost every big-name platform: Weibo, Douyin, iQiyi, Kuaishou, Tencent, QQ, Youku, Kugou, Bilibili, Kuwo, Migu, Toutiao, and Xiaohongshu.

On 15 December 2021, the Hongfan Institute of Law and Economics 洪范法律与经济研究所 attempted to host a livestream, in which Li participated, on the subject of procedural justice in the punishment of ‘immoral’ artists. Just as they started talking specifically about the mechanisms by which artists banned by CAPA can dispute their ban, the video sharing platform Bilibili shut down their livestream. They then moved the livestream to Weibo, which also shut it down and then muted the account for five days. Recorded livestreams of this session were later posted on Youtube, including part 1, part 2, and the full, non-livestreamed recording.

When Beijing’s Chaoyang police department accepted Zhang’s defamation case (it remains unclear whether Zhang is suing CAPA directly) on 24 December 2021, Li and fellow netizens created over twenty variations of the hashtag #北京警方受理张哲瀚案件# (Beijing police accept Zhang Zhehan’s case); all hashtags were deleted soon after. Since Li started questioning CAPA, he has created several of Weibo hashtags, including #人民的公义# (justice for the people), which garnered over 10 billion views collectively before the hashtags were deleted. None of his hashtags ever made it onto Weibo’s hotsearch rankings despite frequently generating engagement well above other hotsearches at the time. Li’s Weibo account was silenced on 7 January and permanently deleted on 8 April 2022.

Though there is no confirmed evidence that links CAPA to the smear campaign against Zhang in August, many of the tactics used against Li, including mass silencing of opposing views, and manipulation of media and public opinion, are reminiscent of those used against Zhang. It is unclear why CAPA would want to erase Zhang. A popular theory is that someone in CAPA wanted to eliminate a strong competitor from the industry — perhaps Zhang got a coveted role instead of another actor who was a member of or had connections within CAPA, for example. Because of how opaquely the entertainment industry operates, we may never know the real reason.

A desire for improvement

In 2021, we saw the high-profile cancellation of many celebrities, including some who were convicted of real crimes and others who were not, like Zhang Zhehan as well as his former boss, the popular actress, director, and producer Zhao Wei 赵薇 whose name was even more mysteriously erased from the Internet in August 2021. But since Li Xuezheng’s efforts to question the procedural fairness behind the punishment of artists, we see more and more online discussion of the issue and denunciation of the spread of misinformation, the defamation of celebrities, and the enormous cost of unjust social death.

On 1 January 2022, Li posted a voice recording of an interview with Zhang on Weibo, the first time Zhang was given a platform to speak since his cancellation the previous August. In it, Zhang described the fear and self-doubt that he and his mother had gone through as a result. Zhang mentioned that at one point he was even afraid to go outside, and that both he and his mother wondered if the only way to prove their innocence was through their own deaths, since they had no other way to speak out. This interview followed a letter from Zhang’s mother, also posted by Li, in which she described how Zhang broke down after his beloved four-year-old nephew told him he was a bad person. The interview with Zhang was deleted soon after by Weibo, and now, with the deletion of Li’s account, the letter from Zhang’s mother is gone too.

The misinformation that led to Zhang’s cancellation and the subsequent deletion of clarifications drew the scrutiny of legal professionals as well as the anger of Zhang’s many fans, including Twitter user axhuuuu who created this image.

Through Li’s platform, Zhang’s case generated a tremendous public outcry against misinformation and cyberviolence. While it’s clear there is widespread popular support for improving China’s online environment (see recent article from Global Times), progress is slow. Though CAPA has been less visible in recent months, it has certainly not disappeared. It was still recruiting new members as of 11 April 2022, although it is finally being audited by the Ministry of Civil Affairs (MOCA) this year. The auditing process will include examining any organisation self-regulation policies and the effectiveness of their implementation as well as the standardisation of financial and business management policies.

Zhang Zhehan’s story is a great example of how much power a coordinated, monopolistic industry organisation can have and how much damage it can do to individual lives and reputations. Despite overwhelming public sentiment in support of Zhang Zhehan, he still does not have his Chinese social media accounts back and is unable to speak out for himself. Given the enormous power the industry has concentrated within itself, it does not need the explicit support of the government to erase an artist completely. And with the help of pay-to-play media, marketing accounts, and water armies, it doesn’t need genuine public sentiment behind it either.

*This story previously stated that CAPA was not a government organisation and categorically did not take directives from the government. It has been updated at the suggestion of several knowledgeable readers to reflect the degree of uncertainty surrounding this issue.