In September of 2020, Xi Jinping announced China’s commitment to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2060, with an intermediate target of peaking carbon emissions by 2030. This is a considerable challenge given that that country is today still the biggest user of coal globally, by some margin.

In 2019, China was responsible for about 55 percent of the global total consumption of thermal coal (used primarily for electricity generation), and about 60 percent of global consumption of coking coal (used in steelmaking). The large bulk of this is supplied by domestic mines; imports made up 7.2 percent of thermal coal consumption, and 13 percent of coking coal consumption in 2019. Despite this relatively large dependency on domestic suppliers, China has faced difficulties in sourcing secure and affordable supplies of coal for its power and steel plants over the past few years.

Prices for thermal coal in seaborne markets spiked to above US$400 per ton in early May 2022, the highest in at least fifty years, and about five or six times as expensive as usual. Prices for coking coal similarly jumped, to about US$600 per ton, or about four times usual prices. This came at a time when Chinese power and steel plants were already having to scramble to find alternative suppliers following the unofficial import ban on Australian coal in late 2020. The country supplied about 20 percent of Chinese thermal coal imports, and 40 percent of coking coal imports in 2019.

China also experienced disruptions in electricity supply in different parts of the country in both 2021 and 2022, leading to power rationing, and affecting both industrial production and residential consumption.

In mid-2022, Bloomberg’s sources claimed that China was therefore considering lifting its ban on Australian coal imports: the compound energy crises had Beijing so desperate, rumour had it, that it was willing to look past its political strife with Canberra for the sake of renewed access to Australian coal. That storyline, however, does not match very well with the underlying causes of the energy crises, nor with recent developments in Chinese energy markets.

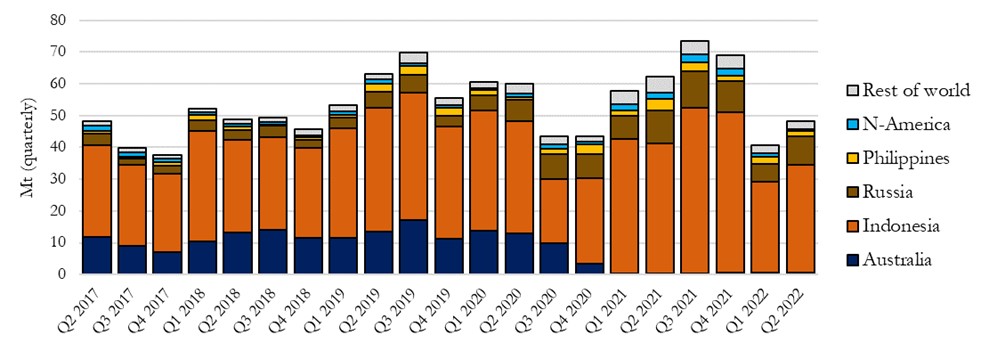

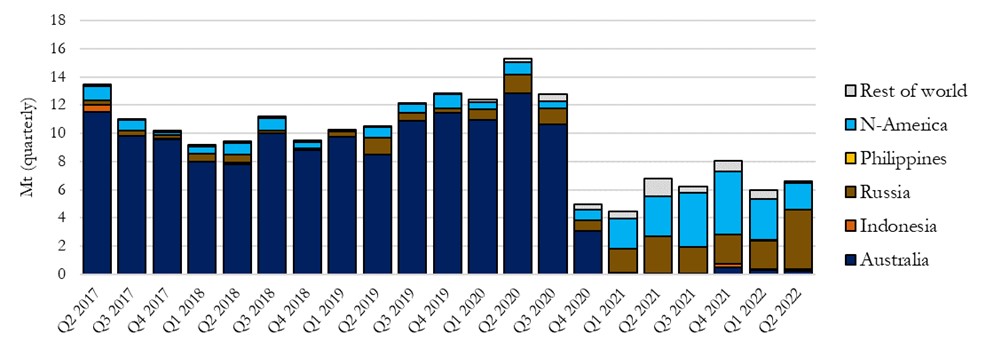

Volatile spot prices for seaborne coal have affected all coal importing countries and have been due mostly to supply issues. Consumption levels of coal, both globally and in China, have returned unexpectedly rapidly to levels seen before the Covid-crisis, whilst supply did not keep up. That was due in part to Covid-induced closures of mines and disruption of transport, again, both globally and in China. Just as Australian exporters soon found new buyers for its coal following the Chinese import ban, Chinese buyers quickly managed to find new suppliers. For thermal coal, it turned to Indonesia, a relatively cheap supplier that was already fulfilling much of China’s needs (Figure 1). It replaced Australian high quality coking coal with imports from the US and Canada, at quite high cost, although Beijing has been working to reduce dependence on these suppliers since. In short: Beijing’s insistence on cutting Australian imports had some upward effect on the prices that its domestic consumers had to pay, but the bulk of those price increases were due to causes that have raised prices for all importers in global coal markets.

Figure 1. Chinese seaborne coal imports (Mt, quarterly) of thermal coal (top) and coking coal (bottom). Note that does not include overland imports from Mongolia or Russia. Data source: Kpler, graph created by author.

The power shortages in the summer of 2021 were largely tied to the high prices in international coal markets, as well as reduced domestic production due both to covid-induced mine closures, and heavy rainfall flooding mines in key coal-producing areas. This led to power shortages due to an ongoing but incomplete liberalization of energy markets in China. Coal prices are allowed to fluctuate according to market dynamics, although the National Development and Reform Commission, the market and pricing regulator, can intervene, mainly with regards to levels of coal production or imports, when prices fall or rise beyond a specified range. Power prices, on the other hand, remain more strictly regulated. For those, market dynamics may cause fluctuations of no more than 20 percent above or below provincial-level benchmark prices. This is already more generous than the limit of 10 percent above benchmark prices in place until October of 2021. That change was enacted after coal-fired power plants, faced with rising fuel costs but limited ability to recoup these through higher electricity prices, stopped producing power altogether to prevent operating at a loss, in some cases claiming a need for maintenance. Decarbonisation policy also contributed to the power shortages, as local cadres sought to adhere to emission targets, even if that meant shuttering factories or denying power to other big power consumers.

The summer of 2022 saw further power shortages, this time during the longest and hottest heatwave in recorded history. This led to increased power demand from air conditioning throughout China, at the same time as the southwestern provinces in particular experienced shortfalls in electricity generation. In these provinces, power production largely relies on hydropower, and was severely hampered by the drought that saw even the water flow of the Yangtze, the world’s third-largest river and an important source of drinking water and vital shipping conduit as well as a crucial source of hydroelectricity, drop to 50 percent below a five-year average. Supplies of Australian coal would have done little to relieve either power crisis. While the crisis in 2021 was related to the high cost of imported coal globally, the crisis in the summer of 2022 would not have been solved with more Australian coal. Domestic production of the fuel was already back at record levels, but the power networks in the southwest needed water, not coal, to operate.

Wider developments in China’s coal markets have further reduced the need for imported coal in general. First, while Chinese covid stimulus measures have typically mostly spurred carbon-intensive economic activity, the growth of coal-fired power consumption appears to be plateauing. Throughout the first six months of 2022, coal-fired power consumption was down 3.9 percent. If that percentage reduction would be maintained over all of 2022, thermal coal consumption would be down by 89 Mt, although the reduced hydropower output throughout the heatwave will have created some additional, though temporary, demand for coal-fired power.

The future looks brighter, as provincial level governments have announced plans for renewables that, when added together, would result in 1,200 GW of solar and wind installed by 2025, a level of installations targeted by the national government for 2030. China has always been a big market for solar PV, with 55 GW of installations in 2021 alone, equal to about one third of the global total. Over the first eight months of 2022, Chinese investment in solar PV was up by a whopping 323.8 percent on last year. Steel output also appears finally to have peaked, down 6.5 percent from last year, equivalent to an annual reduction in coking coal consumption of 46 Mt. Continued concern over the health of the real estate sector, one of the biggest consumers of steel, will certainly weaken the outlook for future steel demand. To put those numbers in perspective, over the period 2018 to 2020, China’s average annual imports of thermal coal were about 225 Mt, and imports of coking coal were about 75 Mt.

Chinese plans for improved energy security further reduce the need for coal imports. Over the first eight months of 2022, domestic production of coal was up by 10.9 percent. If that same percentage increase in production keeps up over all of 2022, it would result in an astonishing 445 Mt additional output of coal; well more than total Chinese imports in a typical year.

Combined with reductions in consumption, this will lead to massively increased stockpiles or drastically reduced imports, and probably both. On top of this, in late 2019, China opened the HaoJi railway, which can carry 200 Mt of coal from China’s key coal mining centre of Ordos in Inner Mongolia to its central provinces, the ones most badly hit by the 2021 power shortages. This cuts the delivery costs of coal and lessens the need for imports. Another new railway links China’s steel making heartland in Hebei to the Tavan Tolgoi mine complex in neighbouring Mongolia, which supplies high quality and cheaply mined coking coal. Again, this will lessen reliance on seaborne coal imports.

In summary, China is reducing and will continue to reduce its consumption of coal. It will source the coal that it does consume increasingly from domestic mines, as well as from Mongolia, which has few other markets to sell to given its geography, and Russia, constrained in its exports by the international sanctions due to its invasion of Ukraine.

When and if China offers to drop the import ban, it will not be because it is desperate for Australian coal, but rather because it no longer needs it.