Louisa Lim, who was raised in Hong Kong, has covered China and Hong Kong many years as a journalist. A senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne, she is also the co-host of The Little Red Podcast. Her previous book, The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize.

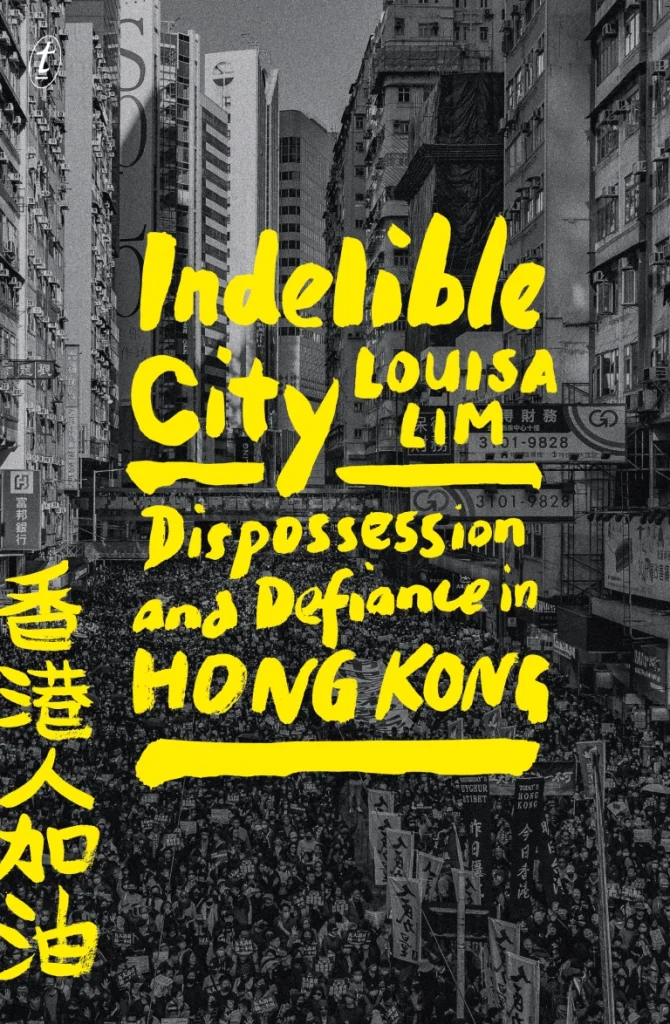

China Story editor Linda Jaivin interviews Louisa about her latest book — Indelible City: Dispossession and Defiance in Hong Kong, New York: Riverhead Books, 2022 — which looks at the durability and characteristics of Hong Kong identity from ancient times to the present and restores ‘Hong Kong voices’, in all their power and powerlessness, to the centre of the Hong Kong story.

Q1. The ‘King of Kowloon’ is a man who, convinced that his family owned Kowloon before the British stole it from them, devoted his life to graffiti-ing his genealogical claims to the territory on walls, electricity boxes and numerous other places across Hong Kong. He is a central figure in Indelible City. You even use his calligraphy in your chapter titles. What is it about this marginal yet iconic figure — poor, not well-educated, possibly mad — that makes him the perfect symbol for Hong Kong (so often seen as wealthy, sophisticated, and cosmopolitan)?

I’ve been really interested in the ‘King of Kowloon’ because he is so fungible and flexible as a symbolic figure, and I think that’s why he’s also so attractive. He’s an almost prismatic figure. How you interpret his symbolism depends on the angle from which you’re looking at him. Very early on, people mainly talked about the fact that he was working-class, marginalised, an outsider, and there was very little discussion at all of his claim over the land, the idea of sovereignty. That was something that came up later as the situation changed in Hong Kong. People began to label him the first localist, but at the same time he was also becoming a brand that represented Hong Kong, a shorthand for Hong Kong. He was commoditised by actual brands, big and small, from the high-end fashion designer William Tang, all the way down to Goods of Desire, who reproduced his calligraphy on underwear and bags – you can buy cushion covers and everything. So he became a commodity as well. Later he was seen as an artist even though he never saw or called himself that. I think it was that potential for him to be viewed in different ways across time that attracted me. When I was doing the ABC podcast, the ‘King of Kowloon’, I talked to people like the legislator Ted Hui, now in exile in Australia and he described the King of Kowloon as ‘a prophet’. Other people called him a shaman. That whole change in the way people viewed him attracted me as a writer, as well as the idea of a mystery, a story that you could really unpack and explore – I’ve always been interested in stories that are hard to tell. I like the challenge and this to me was this sort of ultimate journalistic challenge.

Q2. Discussing Hong Kong’s multiple historical identities and frequently redrawn borders, you liken Hong Kong to a ‘shimmering chimera that was constantly changing shape depending on the angle of viewing.’ You grew up there, worked there as a journalist, have been a visitor and even protester. How has its shape changed in your view?

No place is static, but I think Hong Kong has really changed, and in so many different ways. Its shape has changed physically over the years since I grew up there. The harbour has grown smaller and smaller, and whole areas of the sea have been reclaimed, to make the airport of Chek Lap Kok, for example. So the actual physical shape of Hong Kong has changed, but also its height, as skyscrapers have become ever higher. There have been these physical changes, but there have been other changes as well: it’s a place in motion. But what we see now is an attempt by the Hong Kong government and China to pin down Hong Kong, to cement one version of it and one version of its history — the official narrative. How Hong Kongers have seen themselves and Hong Kong has also changed over the years. Early on it was much more of a sojourners’ place, where people went on the way to somewhere else. It was only in the sixties and seventies that that began to shift. These new cities were being built in the New Territories. You were getting more than one generation of families born in Hong Kong, and it became not just a social destination but a home. Now with these political changes, how the people view Hong Kong is changing yet again and for many Hong Kongers those changes are turning the city that has been home into something quite unrecognisable.

Q3. You write that the history of Eurasians in Hong Kong — a community you have been part of — is one of ‘disappearance’. On the one hand, they were often, as you say, ‘excluded from the clan lineage records that anchored Chinese identity’. On the other, they ‘erased themselves from sight.’ How did this happen, and what does the future look like for Eurasian and other non-Chinese Hong Kong people under the increasingly nationalist regime?

It’s a feature of the history of Eurasians that they have not just been excluded from versions of history, even family history, but that they have excluded and erased themselves. We see that from historical records in the nineteenth century when the very category of Eurasians disappeared, as noone was willing to identify as Eurasian, even though the actual number of Eurasians was increasing at the time. To me, that idea of self-erasure is really tragic.

Back then it was so difficult, almost impossible, to function as someone who was both Chinese and Western. They would have to choose either to be Chinese, or to be Western, and very few Eurasians managed to navigate that successfully. The nationalism nowadays in Xi Jinping’s China and the Communist Party’s conflation of state and Party, its capture of the very notion of Chineseness is, I think, really alarming for Eurasians and non-Chinese Hong Kong people as well. It’s deliberately exclusionary, and that bodes ill not just for Eurasian people but for Hong Kong’s future as an international city.

Q4. One of the interesting aspects of your book is how, in contrast to so many histories of Hong Kong that begin with the Opium Wars, you examine its ancient histories and myths. One of your interviewees remarks that the King of Kowloon struck such a ‘deep chord’ in Hong Kong because ‘the Cantonese mindset is characterised by a subversive and revolutionary yearning for lost dynasties.’ What does this mean, and why have we not got that memo sooner?

According to Chinese history, Hong Kong was the place to which the last heirs to the Song dynasty fled, and that act of imperial flight left a profound mark on Hong Kong culture. The site of enthronement still exists — there’s even an MTR station named after it — and there’s also a popular feast dish of various delicacies layered in a large bowl — pun choi — that supposedly dates back to that time. My interviewee was also referring to Hong Kong’s physical and political distance from the imperial centre of power, and how that helped shape a rebellious, subversive mindset, which was then amplified by the use of a different language, Cantonese, from the imperial centre. I think that memo — as you put it — hasn’t been passed on because it has not been in the interests of Hong Kong’s successive colonial rulers to frame Hong Kong identity in those terms. Instead, both the British and the Chinese rulers of Hong Kong have hewn closely to the same message: that Hong Kongers have always been purely economic actors without much interest in politics. This has never been true, but it seems they hoped that if they repeated this fiction enough, even Hong Kongers would come to believe it. We can see from the events of the last ten years how wrong that turned out to be.

Q5. What is it about Cantonese, as spoken in Hong Kong, that is so central to Hong Kong identity — and what role has it played in the various protests?

Cantonese is central to Hong Kong identity, because it is the language of Hong Kong, and I use the word ‘language’ advisedly. Many scholars would argue that Cantonese is closer to Classical Chinese than Putonghua, or the standard Mandarin that is spoken on the mainland. In its written form, Cantonese uses ancient participles and fantizi, the traditional characters that are no longer used on the mainland. Cantonese is integral to the Hong Kong identity in many ways. One, because it is not the language of the mainland — until recently, even the Cantonese spoken across the border in Guangzhou was different from the Cantonese spoken in Hong Kong. Just learning it and speaking Cantonese can be an act of assertion of a separate identity. The nature of Cantonese is profane, it’s sweary, it’s a little bit subversive. The role it has played in the protests has been really interesting. It’s much more flexible than Mandarin. There is this linguistic inventiveness of a level not allowed on the mainland. Protesters were even creating new characters. The most famous example was the creation of a character for ‘freedom c**t’ — using a combination of the three characters that make up freedom 自由 and c**t 閪 (see illustration below) — a phrase that a policeman used against some protesters early on. The protest movement appropriated it and made all these posters and t-shirts using this new Chinese character ‘freedom c**t’, written in Roman letters as ‘freedom-hi’ after the Cantonese pronunciation. These new Chinese characters were unintelligible to mainlanders.

Source: Kitty Hung’s Facebook page, for more on this term see here.

Q6. During the Occupy Central with Love and Peace movement of 2014, one of the protest’s leaders, Benny Tai, told you that ‘Hong Kong laws provide the protection for us to have this kind of movement’. Were he and others like him naïve, or were they betrayed, and if so, by whom exactly? Was it possible to foresee the crackdown to come?

I don’t think it’s naive to believe in the rule of law, or to believe in a government that upholds the rule of law. It might have been naive to believe that a government ultimately loyal to the Communist Party of China would uphold a common law system in its jurisdiction, but that’s exactly what ‘One Country Two Systems’ pledged. When he was sentenced for the Umbrella Movement, Umbrella movement co-founder Chan Kin-man said, ‘In the verdict, the judge commented we are naive, believing that by having an Occupy movement we can attain democracy. But what is more naive than believing in One Country Two Systems?’

Hong Kongers have been betrayed at various points in their history by successive rulers in different ways, but this particular betrayal was so painful because Hong Kongers had believed they would be protected by the systems both British and Chinese promised would remain in place for fifty years after the return of sovereignty. There are those who argue that a crackdown was always inevitable, but the speed and scope of that crackdown has been brutal and shocking. I don’t think anyone foresaw how quickly Hong Kong’s institutions would be dismantled, or the huge exodus of Hong Kongers from their home.

Q7. Staying with 2014 for a moment, you describe a poster of the Umbrella Movement that read ‘This is NOT a revolution’ as having ‘said it all’. What is this ‘all’ that it said?

The message was that this was not a movement to overthrow or forcibly replace the government. The Umbrella Movement came after a series of actions working within the constraints of the system to widen the democratic mandate in choosing a chief executive. The Basic Law had always promised universal suffrage but provided no timetable. Methods for widening the mandate included running polls, which more than 790,000 people took part in, to find how the population wanted to nominate candidates for chief executive. The aim was to carry out democratic deliberations on reform through popular consultations. The act of civil disobedience that was Occupy Central was originally intended to be a one-day event. The failure of the government to compromise or give any ground during the Umbrella Movement stoked the dissatisfaction that then exploded during 2019.

Q8. You write that watching the protest movement of 2019, you’d had a feeling that people in Hong Kong had been ‘living in a kind of simulacrum, a political make-believe where our imaginations had been colonised for so long that we were desperate to believe whatever our rulers told us, no matter how much evidence there was to the contrary.’ Is there a danger that in the future – even the near future – that the people of Hong Kong will simply move from one simulacrum to another, this one designed by Beijing?

There is a danger that the people of Hong Kong are moving from one reality to another, but the evidence shows that they are far less willing to buy into Beijing’s political make-believe. In this case, the challenge is epistemological. It confronts Hong Kongers on a daily basis, whether it be through high-ranking officials telling outright lies or legal charges against activists and politicians that are blatantly concocted for political ends. The reality that Hong Kong’s rulers are building is not so much a simulacrum but something more akin to a political re-education territory, where actions and words must be policed at all times to avoid violating ill-defined laws that can be applied retroactively. Hong Kongers’ reaction to this can be seen through the large numbers leaving the territory.

Q9. In 2020 you spoke to the playwright Wong Kwok-kui about a series of historical plays he had created several years earlier about Hong Kong. You write that ‘The very existence of the national security legislation restricted our conversation like a corset.’ If open conversation on Hong Kong identity is now impossible, what are the implications for that identity itself?

The implications for Hong Kong identity are far-reaching. We are seeing a campaign against expressions of Hong Kong identity which is playing out across politics, society, education, and all other arenas. One area that is most concerning is the campaign of intimidation to silence academics who study or research Hong Kong identity itself. We’re seeing the same pattern recurring, which begins with attacks by the pro-Beijing state-run newspapers, and often ends with those academics having to leave their jobs and sometimes to flee Hong Kong. This purge of education has targeted people like the eminent sociologist Ching-Kwan Lee, the political scientist Brian Fong, and cultural studies scholars Law Wing-sang and Hui Po-keung. These attacks muzzle these scholars and try to discredit their work, with the long-term aim of rewriting Hong Kong’s history so that it conforms to the Communist Party of China’s official narrative. I remember in 2019 one of my sources told me that they feared that the phrase ‘heunggongyan’ 香港人 or ‘Hong Konger’ would itself one day be illegal. At the time, I thought they were overreacting. Today I fear that day is approaching.

Q10. You make a convincing case that by August 2021, Hong Kong was no longer what it used to be — culturally and intellectually vibrant and as a haven for political and other non-conformists in the Chinese world. What then is ‘indelible’ about the ‘Indelible City’?

Hong Kong is such a layered place, as literally shown by the city’s walls with their layers of political graffiti. Layers may be covered over, but they often also resurface in unexpected ways and at unexpected times. Even if the outward manifestations of protest are covered up, those expressions of discontent have been written onto the brains of Hong Kongers over the years in a way that cannot be reformatted. I like the contrast this title makes with my last book, The People’s Republic of Amnesia, which refers to the way that the CCP managed to excise memories of the killings of 1989 and silence discussion, even by those who were witnesses. That same playbook will not work with Hong Kongers. Figures show that 140,000 people left the territory in the first three months of 2020 alone. I think that’s testament to the fact that Hong Kongers would rather leave their hometown forever than sacrifice their freedom of thought.