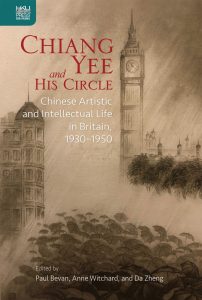

An interview with Paul Bevan, Anne Witchard, and Da Zheng on Chiang Yee and His Circle: Chinese Artistic and Intellectual Life in Britain, 1930–1950, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2022.

Questions prepared by Ke Ren

Q1. Chiang Yee and His Circle was inspired by a pair of events in Oxford in the summer of 2019: the unveiling of an English Heritage Blue Plaque to commemorate Chiang Yee (only the third Chinese figure to be so honoured) and an accompanying symposium at the Ashmolean Museum to celebrate Chiang’s life and work. What is the significance of this public commemoration and renewed attention to Chiang Yee in the UK?

In the summer of 2019, a symposium was held to mark the years that writer and artist Chiang Yee 蔣彝 (1903-1977) spent in Oxford more than half a century before. The symposium was organised by Anne Witchard and took place at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, (at a time when Paul Bevan was working there as Christensen Fellow in Chinese Painting). The papers given were early versions of what would later become the basis for individual chapters of the book, Chiang Yee and His Circle. They were presented by Diana Yeh, Sarah Cheang, Frances Wood, Tessa Thorniley, Paul French and the three editors of the book. Later on, two additional contributors were invited to write chapters: Ke Ren, of the College of the Holy Cross in the US, and Craig Clunas, Professor Emeritus at the University of Oxford. Craig had been a member of the audience at the conference and was involved in organising the erection of a commemorative Blue Plaque in Chiang Yee’s memory. Blue Plaques, erected by various organisations (in the case of Chiang Yee, the Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board) can be seen all over the UK, put up to commemorate people of note at their former residences. To date, only three Chinese figures have Blue Plaques in their memory: novelist, Lao She 老舍 (1899-1966); ‘Father of Modern China’ Sun Yat-sen 孫中山 (1866-1925); and Chiang Yee, who lived at 28 Southmoor Road, Oxford from 1940 to 1955. It is hoped that more will follow. One possible candidate for this might be, Shih-I Hsiung 熊式一 (1902-1991), Chiang Yee’s associate and friend, who also became an Oxford resident in the 1940s. Chiang Yee’s biographer, Da Zheng, was a special guest at the unveiling of the plaque, as well as the keynote speaker at the symposium, having made his way to Oxford from Boston in the USA. Following the symposium, on one of the hottest days of the summer, a number of the audience made their way on foot to where the plaque was to be unveiled. In Southmoor Road, the current owners of the house opened their doors and offered their hospitality to the assembled crowd.

Even though Chiang Yee may not be a household name, there is a growing interest in his books amongst the general reading public and in academia worldwide. It is hoped that this collection will be read by those who are already familiar with his writings, as well as new readers attracted by the fascinating story of Chiang Yee and his circle in the UK.

Q2. This book tells the story of a group of Chinese writers and artists who gathered in the Hampstead neighbourhood in Northwest London in the 1930s. How did this area become such a central node of a diasporic cultural network, and how does this story revise our conventional images of Chinese life in Britain in the early to mid-twentieth century?

In the 1930s, the Borough of Hampstead was home to one of the most vibrant artistic communities in the UK. It was in this area of North London (now in the Borough of Camden), that Chiang Yee and Shih-I Hsiung lived, before they were forced to relocate to Oxford after the destruction of their homes in the London Blitz. While in Hampstead, their neighbours included other Chinese friends and colleagues, the historian Tsui Chi 崔驥 (1909-1950), and poets Wang Lixi 王禮錫 (1901-1939) and Lu Jingqing 陸晶清 (1907-1993), as well as countless other artists and writers, some well-known, others now forgotten. Close by to the homes of the Chinese intellectuals, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth, and Ben Nicholson had their studios. This group of English artists was dubbed ‘A Gentle Nest of Artists’ by their friend, local resident, poet and art critic, Herbert Read.

Just around the corner from them, in Lawn Road, was the modernist block of flats now known as the ‘Isokon’. Built by Jack Pritchard and designed by Wells Coates, it was inspired by continental architectural movements. Members of the Bauhaus who had fled Germany due to persecution from the Nazi government, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and László Moholy-Nagy, all lived for a time in or around the modernist block of flats, working on their own designs in London. Other artists made their homes close by, many of them also having fled Nazi persecution. From the point of view of sheer numbers, perhaps the most notable group of artists was the Artists’ International Association, the mostly left-wing members of which aligned themselves with the Socialist Realism of the Soviet Union.

The single figure who linked these diverse groups together was Herbert Read, a friend and neighbour of Chiang Yee. Read contributed prefaces for two of Chiang Yee’s books. In his publications of the time, Chiang Yee wrote about Read and other friends, the local streets of Belsize Park and Hampstead, and his daily walks on nearby Hampstead Heath.

The Chinese writers and artists have received far less attention than other artists who lived in the area. This book goes some way to revising the conventional view of what made Hampstead famous as a flourishing artistic area in London.

Q3. How did the writings and lectures by Chiang Yee and his cohort help transform British understandings of Chinese culture (including Chinese aesthetics and art in the 1930s) and challenge pre-existing stereotypes?

In the 1930s, the British public’s knowledge of China and ‘the Chinese’ was limited. Exposure to China through films and novels, more often than not, showed Chinese people in a less than complimentary light. Sax Rohmer’s evil genius, Fu Manchu, the murderous Mr. Wu, and Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights: Tales of Chinatown, all displayed highly exoticized versions of an imagined Orient that persuaded a British audience of the iniquities of China and the Chinese people. Chiang Yee and Shih-I Hsiung were amongst a growing number of people in the 1930s who were able to present another aspect of China to the British public. They did this partly through the broadcasts they made for BBC Radio on various aspects of Chinese culture, but also through their published writings. Even though Hsiung’s hit West End play Lady Precious Stream (1934) itself showed a watered down and somewhat distorted version of Chinese drama, he certainly had no intention of displaying China in a bad light, and it became highly popular at a time when a China craze had already taken hold in certain quarters of fashionable British society. It was at this time that Chiang Yee was able to carve out a niche for himself as a writer and artist, with the publication of a series of highly popular books that sold themselves on the notion of Britain seen through Chinese eyes. The Silent Traveller: A Chinese Artist in Lakeland, published in 1937, was the first of these. They helped to transform public opinion about Chinese people in Britain.

Q4. Chiang Yee is known for his persona of ‘the Silent Traveller’ in his widely-read Silent Travellers series. What new light does your book shed on the self-fashioning of cross-cultural identities by Chinese writers and other personalities in Britain?

In the early 1930s, right before his departure for London, Chiang Yee created a new name for himself: Zhongya 重啞, meaning completely mute or dumb. Disappointed by the rampant corruption he had witnessed within in the Kuomintang, the ruling party at the time, Chiang resigned from his post of county magistrate and vowed never again to be involved in politics. Not long after his arrival in London, he began to use the pen name Yaxingzhe 啞行者, that is, ‘the Silent Traveller’. It was a deliberate choice. The word ‘Silent’, or mute, expressed his sense of language inadequacy, uprootedness, and alienation as he strived to establish a new cultural identity in the West. Chiang used this pen name for the titles of his travel series, such as The Silent Traveller in Oxford and The Silent Traveller in New York. People soon realized that this persona — a Chinese man, always wearing a smile on his face, walking slowly and pensively — was in fact extraordinarily observant and wise. He drew people’s attention to things around them that had often been overlooked, and he would make interesting comments both refreshing and convincing. His writings, humorous and relatable, have won the hearts of thousands of readers throughout the world. Chiang’s self-fashioning in this case proved successful, and it was a strategy employed by his fellow writers and friends as well. For example, Wang Lixi, a passionate poet and political activist, adopted the English name ‘Shelley Wang’, after the Romantic poet Percy Shelley. The name underlined similarities between the two in their fiery revolutionary fervor and poetic energy. Clothing and bilingualism are some other examples. Chiang Yee and Shih-I Hsiung often dressed in traditional Chinese scholar gowns or cited Chinese classical poems in their work to remind the public of their cross-cultural identities.

Q5. A notable aspect of this collection of essays is that it touches on engagement by the Chinese in Britain with cultural production beyond writing and art to ballet and film, for example. How does this complicate our understandings of the different cultural spaces and genres open to Chinese artists in Britain at the time?

We think it fair to say that historians have generally overlooked Chinese engagement with cultural production in Britain during the early twentieth century. Histories of the Chinese diaspora are inclined to focus on the dockside communities of working men, with some acknowledgement of transient students, such as the poet Xu Zhimo 徐志摩 (1897-1931), who studied in the US and then Great Britain between 1918 and 1922, for example. Initially we focused just on Chiang Yee, who was equally artist and writer, and who combined these talents to great popular effect. Once we began delving into the histories of his cohort in this country, a highly educated group of men and women, we became aware of how diligently they worked to foster connections with London’s cultural elites. The modernist appreciation of a Chinese visual aesthetic, thanks to the efforts of art critics like Laurence Binyon and Roger Fry, paved the way for the acceptance of an ‘authentic Chinese’ voice in painterly circles. By the 1930s (often in the interests of political anti-fascism) sympathetic publishers, broadcasters, journal editors, theatre producers, composers, and choreographers actively sought out Chinese contributors and collaborators, widening the group’s access to creative work in a range of genres and so encouraging their artistic versatility.

Indeed, Chiang Yee and many other Chinese engaged with various aspects of cultural production, often experimenting and exploring new forms. Anne’s essay discusses Chiang Yee’s stage and costume design for the ballet The Birds. Likewise, Shih-I Hsiung attempted to make films, as Paul Bevan’s essay reveals. And some of these writers prepared scripts for the BBC and even broadcast on its radio programs. Chiang Yee was the first artist in the world to paint the giant panda, promoting its image in his artworks and children’s books.

Q6. As you note in the Introduction, the Chinese personalities featured in this book inhabited ‘a world of literary and artistic interconnectedness and wartime co-operation that is only now beginning to be explored in scholarship.’ How did both the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War Two in Europe condition the writings and public activities of Chiang Yee and his cohort and create new opportunities for other Chinese writers in Britain?

It was following the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in July 1937 that a number of literary editors in Britain, particularly those politically inclined to the Left who viewed Japan’s invasion of China as an act of fascist aggression, began to seek out and publish short stories by contemporary Chinese writers. Among the publications they represented were: New Writing and its highly successful offshoot The Penguin New Writing, Left Review, The New Statesman & Nation, the Times Literary Supplement, The Listener, Life & Letters Today and Time & Tide.

As the brutality of the Japanese occupation of China began to be reported in the West, editors and publishers sympathetic to China’s cause concluded that literature had a vital role to play in bringing about China’s salvation. The writer Hsiao Ch’ien 蕭乾 (1910-1999) commented that the moment ‘China began to exist in the eyes of the British’ was 7 December 1941, when Japan attacked Pearl Harbour. He noted that publishers, radio broadcasters and film studios increasingly approached him to work on cultural projects that might demystify China for the British. All at once, Hsiao found that he was no longer viewed as an ‘enemy alien’ but instead as a ‘member of the grand alliance’. China’s new ally status sparked a higher demand in Britain for books about contemporary China, such as those offered in the Penguin Specials series of short polemical works and many of Gollancz’s Left Book Club titles. Hsiao’s survey of contemporary Chinese literature, Etchings of a Tormented Age persuaded Eric Blair (better known by his pen name George Orwell), Head of the BBC’s Far Eastern Division, that a series on Chinese writers was overdue. World War Two then was a key moment when Chinese writers in Britain, supported by a network of editors and publishers, sought to enhance understanding of their country and their people through literature and other cultural expressions.

Q7. The circle of Chinese writers and artists explored in this volume also includes such figures as Shih-I and Dymia Hsiung, Wang Lixi and Lu Jingqing, Tsui Chi, Hsiao Ch’ien, Chun-chan Yeh, and Yang Xianyi. Did they always collaborate or were their friendships impacted by what one author calls ‘the economy of racial representation’ and if so, how?

The memoirs, biographies, and correspondence which document this period of their lives show that they shared not only their homes, family life and friendship, but also their professional networks. They were generous with their contacts and introductions. For example, Shih-I Hsiung introduced Chiang to his publisher at Methuen and later Chiang wrote Methuen a passionate letter of recommendation on behalf of Chun-chan Yeh 葉君健 (1914-1999). During the war, Chiang recommended Hsiao, Hsiung and later Yeh to the BBC as substitute speakers when he was not available, and he put forward Tsui in discussions over the publication of children’s books about Chinese history for Puffin Books. However, as Diana Yeh’s essay argues, although their association was characterised by collaboration and conviviality, their solidarity as writers and artists was also threatened by the political economy of racial representation. With only a limited number of Chinese artists or writers admitted to visibility, they were inevitably burdened with the expectation that they were representing their ‘culture’ or nation. Contestations over what kinds of ‘Chineseness’ should be represented became fraught with tension. Hsiung participated in this economy out of perceived necessity. His experiences in navigating the British cultural world had shown that he could best gain visibility by crafting an aura of exoticised Chineseness that appealed to a Western audience, hence the popularity of his play Lady Precious Stream. As migrants who were also artists they had a shared calling — that of contesting dominant perceptions of the Chinese circulating in Europe and the USA. Yet the way in which they carried the burden of representation tested their relationships. Not only Chiang and Hsiung, but also many other prominent diasporic Chinese figures in their circles at the time, came to confront each other as competitors, rather than allies.

Q8. One key shared experience among these Chinese writers and artists is that of exile, exacerbated by the Japanese invasion of their homeland. Yet Britain too was threatened with aerial attacks. They had to choose whether they would stay in Britain, return to China, or move elsewhere. How do themes of exile, displacement, belonging and community figure in their life, work, and legacy?

This is an important question. Indeed, the Japanese invasion in the 1930s affected these Chinese writers and artists stranded in Britain. While some went back to China to participate in the war of resistance, many stayed overseas. Among them were Chiang Yee, Shih-I Hsiung, Tsui Chi, Hsiao Ch’ien, and Yang Xianyi 楊憲益 (1915-2009). It was devastating since they were thousands of miles from their homeland, and they were constantly worried about the safety and whereabouts of their family members and friends. Then in September 1939, war broke out in Europe. London was no longer a safe haven, and they had to evacuate to neighbouring cities. Despite all this, they forged ahead courageously, promoting Chinese culture, educating the public about the significance of the Chinese resistance against Japanese invasion, and raising funds for aid to China. After the Chiang Kai-shek government fled to Taiwan in 1949, and the communists established the People’s Republic of China, many of these Chinese nationals faced a new round of difficult choices: returning to China, moving to Taiwan, or remaining overseas as stateless citizens. Chiang Yee, Shih-I Hsiung, Tsui Chi, Sye Ko Ho, Ling Shuhua, among others, decided to stay abroad. They faced serious challenges. To survive, they had to take up new jobs. For example, Sye Ko Ho and Kenneth Lo, both former diplomats, ended up in the restaurant business, and Hsiung accepted a poorly paid, short-term teaching appointment at Cambridge. For the next two decades, they could not visit mainland China because of the Cold War, nor could they communicate freely with their families there. Frances Wood’s essay, ‘Mahjong in Maida Vale’ vividly reconstructs the daily lives of the wives of Chinese exiles in London in the 1950s. These women gathered together, playing mahjong and cooking, as a way to empower themselves and support each other. It reminded us of Amy Tan’s popular novel The Joy Luck Club, which was set in the United States.

Q9. In recent years, there have been rising tensions in China’s relationship with Britain and the West. At the same time, we have also seen the rise of anti-Chinese sentiment and anti-Asian violence during the COVID-19 pandemic that has severely affected Chinese diasporic communities around the world. How might the cross-cultural stories of Chiang Yee and his fellow artists and intellectuals help mitigate recurrent misunderstandings of overseas Chinese in our own time?

There has been frequent media coverage about anti-China sentiment and anti-Asian violence in the past few years. This is a very disturbing phenomenon. Nearly a century ago, when Chiang Yee arrived in Britain, he observed widespread discrimination, prejudice, and misunderstanding. Films, stage productions, and publications portrayed Chinese as ignorant, dirty, sinister, and backward.

Chiang Yee, Shih-I Hsiung, and other fellow Chinese often met young children on the street who chanted racial slurs at them. Sarah Cheang’s essay ‘Being Chiang Yee: Feeling, Difference, and Storytelling’ discusses Chiang’s responses to that. Chiang was conscious that some people would view him as inscrutable and odd simply because of his Asian features. Rather than feeling upset or reacting angrily, he used humor and diplomacy, turning those otherwise unpleasant experiences into opportunities to display his human side, make connections, and show commonalities between the East and West. Chiang Yee believed that all human beings, despite differences in language, religion, skin colour and cultural practices, share essential values. He explored those commonalities through travel and travel writing. Chiang Yee and his fellow Chinese writers saw an urgent need for mutual understanding and appreciation, and they dedicated themselves to introducing Chinese culture to the West. Today, as we are confronted with the politics of race and racism in our society, interpersonal communication and cultural exchanges are still an effective way to eradicate prejudices and misconceptions and to bring people together. In that sense, Chiang Yee and His Circle is a timely publication. It is not just a new interpretation of the historical past; it also offers an inspiring direction for moving forward.

Q10. How can interested readers access original writings and artworks by Chiang Yee and the other Chinese artists and authors? Are there reprints and translations that you could point us to?

There has been a growing interest in the cross-cultural contributions of earlier generations. Beginning in 2002, seven Silent Traveller titles have been reprinted in Britain and the United States. Since Chiang Yee’s books were mostly written in English, targeting the audience in the West, his books were not available in bookstores in China for half a century. Since 2005, eight Silent Traveller titles have been translated and published in Taiwan and China. Readers also welcomed Chinese translations of his novel The Men of the Burma Road, the memoir A Chinese Childhood, and the monograph Chinese Calligraphy. Likewise, many of the writings by Shih-I Hsiung, Hsiao Ch’ien, Wang Lixi, Yang Xianyi have been translated or published in Chinese and English. Chiang Yee and His Circle includes a bibliography, which lists a number of related publications and is a good source of broader information. It is our hope that the book will stimulate scholarly interest in the field and lead to more discussion and further discoveries about the Chinese in Britain during the twentieth century and beyond.