The digital age has brought new complexity and new conundrums to China’s one-party rule. While dissidents continue to be summarily arrested and charged with serious crimes, official rhetoric and vox populi now jostle for attention on the Internet.

Collective Strolls

(jiti sanbu 集体散步)

Though public protest is largely banned in China, over the last few years a milder form of demonstration has developed. ‘Collective strolls’ allow citizens to express dissatisfaction in a non-explicit yet overt fashion. Participants in such strolls do not hold up banners or chant slogans. The apolitical and leisurely connotations of the word ‘stroll’ (sanbu) help soften the confrontational aspect of protests. It also makes it easier to avoid Internet censorship of keywords like ‘demonstration’ so that participants can organize online.

Group walks have usually been launched in wealthy coastal cities in reaction to concerns about the environmental impact of infrastructure or industrial projects. Such protests are rarely in response to issues of fundamental governance, human rights or the legitimacy of the rule of the Party. They tend to be, to use an American expression NIMBY – Not In My Backyard – protests. In early 2011, there were calls for Chinese citizens to organize a ‘Jasmine Revolution’ in China. Some included the suggestion that protests take the form of collective strolls.

The expression ‘collective stroll’ first appeared online in June 2007, when people in the city of Xiamen, Fujian province, took to the streets to protest against a paraxylene (PX) factory that was under construction and that they feared would pollute their neighborhood. In January 2008, homeowners in Shanghai who disagreed with land acquisitions for the building of an extension of the city’s famous Maglev high-speed train put on another collective stroll. In August 2011, residents of the city of Dalian organized a collective stroll in protest over another PX factory that, according to media reports, drew over 12,000 people.

All of the above-mentioned protests were successful in their aims. Construction on the PX factories in Xiamen and Dalian was halted. There has been no follow-up in the media about new plans for these factories; they will presumably be built in places where people are poorer and less networked and easily prevented by local toughs from collective strolling.

The McDonald’s store on Wangfujing, Beijing, where online postings called for ‘Jasmine Movement’ protesters to meet on 20 February 2011. Most of the people who gathered on that day were foreign journalists, police officers and shoppers curious as to why there were so many police and cameras at a fastfood outlet.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In China, 2011 turned out to be the year that people were simply not allowed to ‘say it with flowers’ – at least not jasmine flowers as the government, panicked over the potential ripple effects of Tunisia’s ‘Jasmine Revolution’, placed a nationwide ban on the much-loved jasmine. As popular revolt spread across the Middle East during what became known as the ‘Arab Spring’, Chinese rights activists saw an opportunity to initiate their very own ‘Jasmine Movement’.

In February 2011, a loose worldwide coalition of anonymous Chinese netizens posted notices on Twitter and Chinese-language websites hosted outside China urging people to assemble at select venues in thirteen Chinese cities at 2:00pm on 20 February. This was to be the first of a series of weekly rallies protesting against the state and Party’s abuse of power. They weren’t called rallies but ‘collective strolls’ (jiti sanbu 集体散步). The notices circulated briefly on QQ and other mainland-based microblog services before they were censored by the Internet police.

On the day of ‘Jasmine protest’, the anonymous organizers of the movement posted an open letter on the Internet. Addressed to China’s National People’s Congress the letter demanded government accountability and concerted action against corruption and misrule. The letter-writers insisted that the planned rallies were a demonstration of public concern, not an overt threat to the existing political system. The organizers claimed:

We don’t care if China implements a one-party system, a two-party system, or even a three-party system, but we are resolute in our request that the government and its officials accept oversight by ordinary Chinese people. Furthermore, we call for an independent judiciary. This is our fundamental demand.

Not surprisingly, the letter was immediately suppressed.

Police, meanwhile, were turning out in force at the chosen protest venues. In Beijing, a modest crowd of around a hundred people gathered outside the McDonalds in Wangfujing, the premier shopping mall in China’s capital. The police dispersed the crowd before a single slogan was uttered. In the weeks that followed, an increased police presence in Beijing and other cities ensured that the movement would not gain any visibility, let alone traction. China’s ‘Jasmine Movement’ was over before it began. Nonetheless, this brazen if toothless attempt to hold the party-state to account caused acute anxiety among the Party’s leaders. They swiftly moved to place a blanket ban on the word ‘jasmine’ (molihua 茉莉花) on the Chinese net. One casualty of the censorship was a video featuring Hu Jintao, the Party General Secretary and President of the People’s Republic, singing the well-known Chinese folk song ‘Lovely Jasmine Flower’ (Hao yi duo molihua 好一朵茉莉花). It was something that beleaguered Chinese netizen activists widely gloated over.

The logo of the Jasmine Cultural Festival in Hengxian, Guangxi province, cancelled in 2011 due to official sensitivities surrounding the word ‘jasmine’.

Source: Molihuajie.com

Official panic mounted as the scent of jasmine spread through the Middle East. Guangxi province in south-west China cancelled its annual International Jasmine Festival in Heng county. Heng county boasts of China’s largest jasmine plantation; it is locally known as ‘the hometown of jasmine’. Regardless of the economic impact on growers, sales of the flower and the plant were also halted. Meanwhile, local police in Beijing called in flower vendors to force them to sign pledges not to stock jasmine. One jasmine grower was described ‘glancing forlornly at a mound of unsold bushes whose blossoms were beginning to fade’ as he observed that the plant had plunged to a third of its previous market value.

The mainstream media in China was characteristically silent about the ban on jasmine. Three months passed before the authorities felt sufficiently confident to allow Guangxi to hold its jasmine festival after all; only in August did Heng county finally become a hive of jasmine-related activity once more. The belated festivities included a gala concert featuring well-known celebrities like the Taiwan Mando-pop groups Shin and F.I.R., the Taiwanese singer-producer Jonathan Lee (Li Zongsheng) and China’s own pop stars such as Allen Su (Su Xing), winner of Hunan Satellite TV’s 2007 Superboy contest – a highly popular national talent show based on the ‘Idol’ format.

Jasmine Revolution

(molihua geming 茉莉花革命)

Inspired by the Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia and the Arab Spring in February and March 2011, anonymous Internet users urged their fellow citizens to have their own ‘Jasmine Movement’, and protest for democracy. The messages circulating online called for weekly rallies, sometimes using the term ‘strolls’. The first rally on 20 February 2011 attracted a handful of curious observers and a few people who appeared ready to protest. These were outnumbered by scores of foreign journalists and hundreds of uniformed and plainclothes police.

The online calls led to a massive deployment of security forces nationwide, at least thirty-five arrests and the harassment of the foreign media. The harsh especially harsh treatment in 2011 dealt to activists, lawyers, and civil-society advocates like the artist Ai Weiwei seemed to stem from the government’s fear that a Jasmine Revolution really might materialize.

Over the years, after an initial hostility to pop music in the early 1980s, the Chinese government has come to support and encourage this type of entertainment. It generates revenue while conveniently projecting an image of cultural ‘openness’, both locally and internationally. In 2011, such gala concerts and shows had the effect of distracting public attention away from the most egregious suppression of dissent and protest in recent years. Singers crooned and dancers pranced while hundreds of activists and social critics were called in for questioning and threatened into silence, many detained, some indefinitely, for an alleged connection with the ‘jasmine’ threat. The more risible aspects of the crackdown, so poignantly illustrated in the misfortunes of the lowly jasmine, its cultivators and vendors, contributed to the tabloid view of an ‘unfree’ China posing a threat to the ‘free’ world.

Yet by simply equating China with autocratic rule, the notion of ‘the China threat’ reduces the complex realities of life and society in the world’s most populous nation to a black-and-white image of an oppressor state bearing down on its abject people. Such cartoons loom large each time there is a political crackdown in China. But as Peter Ford noted in The Christian Science Monitor in late 2011, most informed observers of China agree that: ‘What China wants is pretty straightforward and unexceptionable: to be prosperous, secure, and respected.’

The party-state’s draconian (and frequently counter-productive) actions exact a heavy toll on the country’s rights movement and activists. At the same time, relations between the state and society are in a dramatic state of flux. Despite the best efforts of the authorities to control the flow of information in and out of the country, international and local events now have a direct, immediate impact on public opinion in the People’s Republic. The Internet has to an extent turned the once formidable force of state censorship into a blunt tool of limited use, one that is far from uniformly successful in deterring the public airing of complaints and grievances. In the digital age, the state must brace itself for myriad, unpredictable public responses every time it exercises coercive power.

Voices in Contention

For most of the twentieth century and since, mainland China has known only one-party rule. It began in 1928 with the Nationalist or Kuomintang government under Chiang Kai-shek, the enemy-predecessor of the Chinese Communist Party which, following a vicious civil war and defeat in 1949, removed the Republic of China to Taiwan. One-party rule in China has generally resorted to a set of national values and beliefs – an ideology – to foster unity and kept them alive in society at large. Formal education, propaganda campaigns and other forms of instruction in the workplace and local community inducted young people into this set of values and beliefs.

The economic reforms that the Chinese Communist Party under Deng Xiaoping introduced from late 1978 required a more flexible approach to the life – and the mental world – of China. By combining elements of Party ideology with the notion of economic liberalization the theoreticians came up with the slogan: ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’. Unlike the first fifty years of one-party rule between 1928 and 1978 (first under Chiang Kai-shek then, after 1949, under Mao Zedong), post-Maoist China has seen a more fluid use of ideology, combining Party propaganda with marketability.

The Top Ten Celebrities of 2011

- Andy Lau (Liu Dehua 刘德华) – popular Hong Kong singer, producer and philanthropist.

- Jay Chou (Zhou Jielun 周杰伦) – Taiwan-born pop star who debuted as a Hollywood actor in The Green Hornet (2011).

- Faye Wong (Wang Fei 王菲) – Beijing-born and Hong Kong-based pop star.

- Jackie Chan (Cheng Long 成龙) – Hong Kong actor, director, kungfu star and eternal celebrity.

- Yao Ming 姚明 – superstar basketball player for the Houston Rockets who retired in 2011 due to injury.

- Donnie Yen (Zhen Zidan 甄子丹) – Hong Kong’s most popular action star; played Guan Gong, the God of War, in the Chinese blockbuster The Last Bladesman (2011).

- Zhang Ziyi 章子怡 – an actress once described by Time magazine as ‘China’s gift to Hollywood’, best known outside China as the star of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Memoirs of a Geisha.

- Jet Li (Li Lianjie 李连杰) – martial arts actor, film producer and international star who has appeared in over forty films.

- Fan Bingbing 范冰冰 – popular actress sometimes called ‘China’s Monica Belluci’.

- Zhao Benshan 赵本山 – China’s most successful comic performer; has a wise-guy persona.

The 2011 crackdown shows how the Party now defends its authority. While suppressing information in China about the detention of wellknown rights activists like Ai Weiwei, Chen Yunfei, Jiang Tianyong, Ran Yunfei, Tang Jitian and Teng Biao, some of whom have been mentioned in Chapter 3, the state-run media trumpeted the government’s achievements in economic and social reforms. In an editorial titled ‘China is Not the Middle East’, the official Communist Party mouthpiece, People’s Daily, reminded its readers of the government’s ceaseless toil on the nation’s behalf. Published on 3 March 2011 in Chinese and English, the editorial was clearly intended both for a local and an international readership.

It described the situation in China as one which: ‘the Chinese can fully participate in and discuss affairs of state, under the existing legal system and democratic system.’ It warned that those who ‘incite unrest’ posed a threat to the orderly and timely achievement of social and political reforms and that ‘street corner politics’ only hindered and exacerbated existing inequalities. The article lists some of the government’s achievements, such as the expansion of the tertiary educational sector and the enrolment of one in four Chinese between eighteen and twenty-two in college education. No mention was made of the major cases of corruption and fraud that have bedevilled the haste of China’s own ‘education revolution’, or the protests they’ve engendered. Instead, it presented one-party rule as a form of conscientious and caring governance: ‘Chinese leaders have always accorded with the public will’, the writers declared. ‘They pursue developmental and reform strategies to solve the problems that have emerged in the process of development and reform.’ This tautology, which is typical of China’s official voice, reflects a lack of vision beyond immediate short-term goals and offers its lame conclusion that: ‘China is not the Middle East’. It’s a negative comparison that, without irony, casts China as a lesser evil: a more benign autocracy, not like those others being overthrown by their angry and fed-up citizenry.

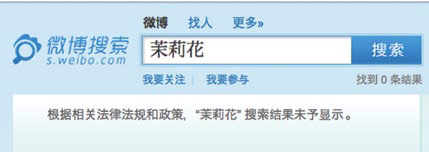

A screenshot of the message that Sina Weibo has shown users searching for jasmine flowers 茉莉花 from March 2011: ‘According to relevant regulations and policies, results for a search for “jasmine flowers” cannot be displayed.’

Source: Sina Weibo

The authorities invoked ‘social justice’ as a guiding principle throughout the 2000s even as popular anger mounted due to government inaction on social injustices such as corruption, threats to public health and safety and rising living costs. They typically blamed misinformation, rumours and Western media reports for the undermining of public confidence in the party-state. Official unease only increased as it became evident how easy it was for people to bypass official controls to organise mass rallies and protests via social media.

While state censors were quick to block undesirable information from the Internet, netizens were just as fast in getting around the blocks to publicize their causes and protests. As the prominent blogger-activist Ran Yunfei wrote on 19 March 2010 in a post that was promptly censored but widely circulated on websites outside China, one proven method was a Hydra- headed assault: large numbers of Internet users, each registering multiple microblogs to publicize a given piece of blocked information, which could easily be assembled like a jigsaw.

An Internet-user cartoon mocking ‘Green Dam’ (Lüba 绿坝) censorship software introduced in 2009 which was intended to protect China’s youth from pornography and harmful political ideas.

Source: Danwei Media

In response the authorities have invested untold (and unreported) sums in improving what it calls the Golden Shield Project, the official name of what is colloquially known as China’s ‘Great Firewall’. Still, net users are becoming more adept at what they call ‘climbing over the wall’ so as to gain access to information posted on the Internet outside China. Jonathon Keats, a columnist for the US-based Wired magazine, wrote about the highly permeable nature of the Great Firewall: ‘it resembles less a fortress than a speed bump.’ Its real effect is predominantly psychological insofar as it deters the many who are either indifferent to censorship or too lazy to circumvent the system.

As Chapter 7 goes into in more detail, as people learn how to scale the Great Firewall, the state censors develop newer and more sophisticated ways to stymie them. Within China, the lack of transparency in which the state operates and the severity of punishments meted out by the legal system ensure that most website owners err on the side of caution in filtering information on their own initiative. This lack of transparency is also reflected in wildly varying estimates of China’s Internet police force. In September 2002, the BBC made an educated guess that there were already 30,000 ‘net cops’. The mainland media offers far more modest figures; He Guangping, the head of the Public Security Bureau of Guangdong, a province with a population of over one hundred million, stated in January 2011 that the province employed fewer than 1,000 Internet police officers.

Coupled with the Internet police is an army of commentators (of equally unknown number) hired to post online comments in support of the official position on any given issue, or to provide disinformation. In mid 2008, the Far Eastern Economic Review estimated the number of commentators at around 280,000. In late February 2011, coinciding with the government crackdown on activists and social critics mentioned above, people who were able to access Twitter in China noticed a flurry of progovernment posts. The contents ranged from attacks on China’s ‘Jasmine Movement’ for being treasonous, through to the condemnation of the US as seeking to destroy China, its rival, by promoting democracy. Added to this was a torrent of abuse and profanities launched against the protesters. It was reported that several of the microbloggers even adopted the names of Chinese activists and dissidents. These Internet dissemblers are derided as the ‘Fifty-cent Gang’, an epithet based on a widely held belief that they are paid fifty Chinese cents per comment or post.

In 2010-2011, online sales of stuffed toys that looked like alpacas spiked. This was because the animal was associated with the anti-establishment Chinese Internet slang term ‘Grass Mud Horse’ (caonima 草泥马), which had first appeared in early 2009 (see the Chronology for details).

Source: Danwei Media

Government officials have at other times been keen to make a show of magnanimity in response to criticisms of the party-state’s propaganda drive and the Fifty-cent Gang. This is part of a relatively new official rhetorical strategy aimed at presenting one-party rule in a benign light. In an age of instant messaging in which things quickly go viral, the Chinese party-state is straining to pre-empt and placate public anger. So it neither defends nor confirms their existence, letting them cop flak for unpopular policies and displaying a tolerant face while continuing its knee-jerk suppression of dissent in real life.

Fifty-cent Gang

(wumao dang 五毛党)

Fifty-cent Gang refers to Internet commentators hired by the Chinese authorities to post comments favourable to party-state policies in an attempt to shape and sway public opinion for fifty Chinese cents or wumao a pop. The term is also used in a derogatory sense to refer to anyone who speaks out in support of the Chinese government, its policies and the Communist Party (the assumption being that you’d have to be paid to do so).

An incident that occurred at People’s University in Beijing on 22 April 2010 illustrates how keen officialdom was to win the people’s trust. Wu Hao, a leading propaganda official from Yunnan province and a popular media figure, was giving a speech about the new era of transparency in official communications. Just before Wu ascended the podium, a young man approached and showered him with fifty-cent bills. The man later identified himself as Wang Zhongxia, a graduate of the university. When subsequently interviewed about the incident, Wu said: ‘the protest of a Chinese netizen was perfectly normal’ and that, as a government official, he even found the experience instructive. He kept one of the fifty-cent bills as a memento, claiming that it would spur him on to serve the people better. Wu contended that his calm response to a calculated insult was evidence that China had become ‘a more and more open society and nation’. He added a caveat: ‘we must not allow such actions to become a regular occurrence as it is not what the masses need.’

Other Party members who yearn for the ideological certainties of the Maoist era believe this sort of thing shows that the Communist Party lacks a clear sense of direction, principle and backbone. Discontent with the Party’s retreat from core socialist-communist values has long been part of public discourse. With the further acceleration of state-led market expansion throughout the 1990s, there was plenty of social commentary about the large numbers of people who were using Party membership to advance their careers and make money. As the commentators included disgruntled Party elders and revolutionary veterans who served under Mao, the ruling leadership allowed some latitude for this type of criticism, curtailing it only when it started to attract wider attention.

In February 2011, as Geremie Barmé notes in the concluding chapter to this volume, a group calling itself the Children of Yan’an Fellowship mounted an articulate challenge from the left. With the sense of entitlement and self-worth befitting the progeny of Mao-era party leaders, the group’s members produced a document – ‘Our Suggestions for the Eighteenth Party Congress’ (the one scheduled for late 2012; see Chapter 10). They published this advice on their website and encouraged substantive political reform through a return to core Maoist values. The appearance of this document roughly coincided with the open letter issued by the organizers of China’s ‘Jasmine Movement’. Both documents invoked the idea of egalitarian justice. But whereas the ‘Jasmine Movement’ did so in the context of the rights of citizens and the need for an independent judiciary, the Red revivalists focused on ideological retro-rejuvenation and an affirmation of party-state rule.

In the 1950s, ‘red’ symbolized class struggle, the guiding logic of Party rule under Mao. A leading slogan of the day spoke of the need for the country to be led by people who were ‘red and expert’. Expertise (technical, scientific, educational) had to be matched by a zeal for fighting bourgeois thinking and capitalism. It was neither class struggle nor the end of capitalism that excited China’s twenty-first century ‘reds’. They were also beneficiaries of China’s capitalist transformation. Some of their number, such as Bo Xilai, the erstwhile flamboyant Party Secretary of Chongqing discussed in several places in this book, visibly enjoyed the limelight, which may well have also contributed to the downfall of both him and his lawyer-businesswoman wife, Gu Kailai, in 2012. It was obvious they were not poor. (The net worth of individuals belonging to China’s political elite remains unknown but is a favourite topic of speculation on the Internet.) We need to keep this complicated ideological (and rhetorical) landscape in mind as we consider an event that kept China’s one-party system under critical scrutiny in the global media between 2010 and 2011.

Google and Dissent

When Google shut down their mainland-based search engine, some Internet users laid flowers at the Google offices in Beijing as a sign of mourning.

Source: Flickr.com/JoshChin

The event was Google’s statement of 12 January 2010 that the company was contemplating the closure of its China operations. Google announced that it would no longer censor search results on its mainland-based portal Google.cn (established in January 2006 and subject to the same restrictions as other mainland-based portals). Users would instead be re-directed to its unrestricted Hong Kong-based portal. The company also identified a barrage of cyber-attacks originating in China on Google’s infrastructure and services, noting in particular the hacking of gmail accounts held by mainland- and overseas-based rights activists and advocates. Although no mention was made of the criticism Google.cn had attracted previously for complying with China’s censorship system, the statement sought to assure Google users that a ‘new approach’ was underway, one that was: ‘consistent with our commitment not to self-censor and, we believe, with local law [in China].’

The media in China and abroad closely covered the issue. Google’s stance led to hostile exchanges between the US and Chinese governments and was the subject of vast amounts of commentary in China and internationally about Internet freedoms and the future of China’s media landscape. If critics of Chinese government censorship and rights abuses outside China welcomed Google’s statement as a belated affirmation of its ethical motto ‘Don’t be evil’, mainland users of Google.cn mourned the portal’s demise.

On 21 January, nine days after Google’s announcement, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton addressed an audience at the Newseum in Washington. Urging ‘the Chinese authorities to conduct a thorough review of the cyber intrusions that led Google to make its announcement’, Clinton infuriated China’s pro-government commentators by likening state censorship to a virtual Berlin Wall. She said that just as that wall eventually fell, ‘electronic barriers’ would ultimately prove no match for the human need to communicate and to share information. ‘Once you’re on the Internet,’ she said, ‘you don’t need to be a tycoon or a rock star to have a huge impact on society.’

These remarks by ‘Secretary of State Xilali’ (as she is known in the Chinese media) deeply offended the Chinese government. An article appeared in the People’s Daily three days later under the byline Wang Xiaoyang condemning Google for insinuating that the Chinese government was involved in the cyber-attacks. Alluding to Clinton’s Newseum address, the article accused ‘certain Western politicians for smearing China’, alleging that China and Chinese Internet companies were as much victims of hacking as Google. While this clash of official views became a focus of international media coverage outside China, the mainland media were restricted to publicizing the official Chinese position. The Chinese media ran plenty of articles berating Google for making ‘false accusations’. One titled ‘Google Ought to Examine its Own Actions and Apologize to China!’ enjoyed particularly wide circulation on the net. Some websites presented this article as ‘expert commentary’ because the author, Deng Xinxin, was a professor at the Communication University of China in Beijing. Alternative, independent views more sympathetic to Google’s position appeared only to be censored immediately. They did, however, circulate freely outside China.

Hacker (heike 黑客)

In March 2009, a Canadian organization with public and private funding called Info War Monitor published a study that revealed the existence of ‘Ghost Net’, a cyber spying organization apparently based in China that had hacked into hundreds of foreign commercial and government servers. In January 2010, Google famously pulled the servers of its search engine from China, redirecting China-based users to its Hong Kong server. On Google’s official blog, the company explained that one reason for this move was that Google and twenty other foreign companies had been the target of hacking attacks originating in China. Security experts and members of the US military establishment have made similar allegations. The Chinese government’s routine denials of such allegations have done nothing to reassure potential victims, and the ‘cyberthreat’ from China remains a favorite topic of hawkish Internet commentators as well as security experts in the United States and elsewhere.

In April 2012, hackers claiming allegiance to the Anonymous group boasted that they had defaced or hacked into hundreds of Chinese government websites, prompting a spate of international media reports. As it turned out, the affected websites all belonged to small, provincial government organizations; no one from Anonymous has yet released any particularly sensitive information from Chinese government servers.

Also, in the days following Google’s statement, Chinese Google fans laid tributes of candles, cards, floral bouquets, and other symbolic objects on a slab outside the company’s ten-storeyed headquarters at Tsinghua Science Park in Beijing that featured the company logo. Security guards removed these daily offerings. When challenged, one guard replied that without an official permit, floral tributes were illegal. The phrase ‘illegal floral tributes’ soon went viral on the Internet as a symbolic protest against state censorship. Naturally, the phrase was quickly blacklisted. Flowers did not have much luck on the Chinese Internet in 2010-2011.

In a poll conducted from 13-20 January 2010 by NetEase, the company operating China’s highly popular 163.com portal, 77.68 percent of 14,119 respondents wanted Google.cn to stay in China. By April, the furore surrounding Google had died down, though it was briefly revived in June 2010 when the company reported more recent cyber-attacks from China. The People’s Daily promptly published another op-ed deriding Google for stooping to slander and betraying ‘the spirit of the Internet’. In the end, Google did not withdraw from China, despite its declining share of the mainland’s Internet traffic market (Baidu being one of its successful competitors) and frequent complaints from Internet users in China about interruptions to Google services. At the time of writing, Google.cn remains in operation but any attempt to access the portal outside China is automatically redirected to Google.com.hk.

Google’s fate inspired pensive remarks from the Shanghai-based essayist Han Han, China’s leading online literary celebrity and independent commentator (for more on Han, see Chapter 7). Between December 2009 and January 2010, two influential Chinese-language magazines – Asia Weekly in Hong Kong and Guangzhou’s Southern Weekly – named Han Person of the Year. In April 2010, he came second in Time magazine’s 100 Poll (in which readers cast votes for the world’s one hundred most influential persons); he garnered 873,230 votes. (The Iranian opposition politician Mir-Hossein Mousavi was number one with 1,492,879 votes.) By the end of 2009, he was China’s most popular blogger, his blog attracting some three hundred million hits. By July 2011, that number exceeded five hundred million.

In March 2010, an interviewer asked Han for his views on Google’s imminent departure from China. He replied that any candid response was pointless, as it would be immediately censored (as this remark was). Nonetheless, the transcript of the interview circulated on the Web outside China (after appearing briefly on his blog), and savvy mainland netizens were able to access and read it via proxy servers. Han expressed regret about Google’s departure but observed that the company had overestimated the interest of China’s netizens in accessing uncensored content. He claimed uncharitably that most mainland Chinese were so preoccupied with making money they didn’t care about censorship.

Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波

Liu Xiaobo is a writer who has, since the mid- 1980s, been a high-profile figure, first as a literary critic, cultural provocateur and firebrand, then as an activist in the 1989 protest movement. Following his release from prison in 1991, he became an outspoken advocate of political reform and human rights. In 2008, Liu was a key figure in the drafting and propagation of Charter 08, a rambling document calling for democracy and human rights in China and modelled on the Czechoslovak Charter ’77. In December that year, Liu was detained for his Charter 08 activism on charges of ‘inciting subversion of state power’. On Christmas Day 2009, he was sentenced to eleven years imprisonment and two years deprivation of political rights. Liu was awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize for ‘his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China’. The Chinese authorities reacted with a frenzy of vitriol and condemnation of the Nobel Prize committee – and even of Norway itself and its government (which plays no role in the selection of Nobel laureates).

Han also remarked that if Baidu (China’s largest Web company) were to offer people RMB10 (US$1.57) to install a browser that would not only block Google but impose even greater search restrictions, he was willing to wager that more than half of China’s 200 million netizens would gladly accept. Han was wrong on one point, however: he had greatly underestimated the size of the mainland online population. Official figures produced at the time by the state-run China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) in its June 2010 survey put China’s online community at 420 million. But Han Han’s remarks were not surprising: his blog posts often criticized government corruption and public apathy.

When Han accused his fellow-netizens of docile compliance with censorship, he made it clear that he was letting off steam in the hope of encouraging greater awareness in China. In mid-2011, he told Evan Osnos of The New Yorker that he opposed ‘hastening multiparty elections’ as the Party was simply too powerful: ‘they are rich and they can bribe people.’ Summarizing Han’s position, Osnos wrote: ‘Outsiders often confuse the demand for openness with the demand for democracy but in domestic Chinese politics the difference is crucial.’ Indeed – although Han’s blog posts are frequently censored, he has not been harassed or arrested for them.

The limits of political tolerance in China become clear when we compare the government’s relatively benign attitude toward Han Han with the harsh treatment meted out to Liu Xiaobo, China’s best known dissident and recipient of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize. Liu was most recently arrested in December 2008, at the end of China’s successful if troubled Olympic year, for co-authoring and organizing Charter 08 – a petition that, in essence, demanded an end to one-party rule and an immediate transition to a multi-party democracy. Twelve months later, he was sentenced to eleven years in gaol on the charge of attempting to subvert state power.

China’s party-state interpreted the award of the Nobel Peace Prize on 8 October 2010 to Liu Xiaobo as a serious politically motivated affront. Outside the country there was intensive media coverage of the ensuing diplomatic tensions between Norway and China as well as the many international petitions demanding Liu’s release from gaol. The Chinese government initially blocked this surge of news but when censorship proved futile, it moved to condemn the Nobel Committee for allegedly perverting the award’s aims. The state-controlled media repeatedly and uniformly referred to Liu as a ‘criminal’. The Chinese official phrase for staying ‘on message’ is ‘maintaining a unified calibre’ (tongyi koujing 统一口径). In the case of Liu Xiaobo, this consisted of condemning the Nobel Peace Prize; denigrating and attacking Liu Xiaobo’s character; criticizing Liu’s Western supporters as being either misinformed, actively anti-China or both; and, publicizing any international support for China’s position. As Benjamin Penny notes in the following chapter, there were even attempts in China to organize a ‘counter-Nobel Peace Prize’ called the ‘Confucius Peace Prize’ in protest.

My Dad is Li Gang!

(Wo ba shi Li Gang! 我爸是李刚!)

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, there are 149,594 people in China whose ID documents carry the name Li Gang. On 16 October 2010, the name gained national notoriety when twenty-two-year-old Li Qiming 李启铭, apparently drunk, drove his car onto the campus of University of Hebei in Baoding, knocking down two young women. When campus security guards tried to detain Li Qiming he is said to have shouted: ‘Charge me if you dare. My dad is Li Gang!’ One of the women, twenty-year-old Chen Xiaofeng, died in hospital. Outraged Chinese Internet users discovered that the Li Gang who was Li Qiming’s father was deputy director of a district Public Security Bureau in Baoding.

The outcry on the Internet brought the incident to the attention of the central government. Li Qiming was tried and sentenced to six years in prison.

The Li Gang incident epitomized a ballooning social problem: the misbehaviour, often involving expensive automobiles, of the spoiled children of officials and rich business people, known as guan erdai 官二代 and fu erdai 富二代 respectively.

To achieve a convergence of opinion, the government powerfully utilized the full array of information technologies not only in print and TV media but across digital media platforms: websites, online forums, blogs and microblogs. But the Chinese public enjoyed access to these same digital technologies. ‘Microblog fever’ played a critical role in spreading the news of Liu’s Nobel award. As traffic soared on the Twitter hash-tag ‘#Liu Xiaobo’, mainland netizens who accessed the service via proxy servers began forwarding the contraband news within China. Because the name ‘Liu Xiaobo’ was banned on the mainland Internet, coded substitutes soon appeared such as the English-language ‘Dawn Wave’, a literal translation of ‘Xiaobo’. One group of feisty human rights activists in Guizhou – one of China’s poorest provinces – called on netizens to flood the Internet with the message: ‘Good news! A mainland Chinese has won the Nobel for the first time.’ A tit-for-tat ensued with pro-government articles and comments countered by oblique defences of Liu’s award.

Such defiant activity is the product of a society that is being opened up by the easy flow of information across digital platforms. Over coming years, with digital technology becoming more affordable, rural dwellers and the working poor will swell China’s online population. Whereas the authorities are still confident they can guide and mould public opinion with regard to international news in which China has a stake, such as Liu’s Nobel Prize, they take a far more cautious approach when dealing with local incidents that touch a nerve among Chinese citizens.

In October 2010, Liu’s Nobel inflamed mass public sentiment far less than a drunk-driving incident in the city of Baoding in Hebei province, in which a female university student was killed and another injured. Chen Xiaofeng and Zhang Jingjing were roller-skating along a narrow lane on the Hebei University campus when they were hit by a car driven by Li Qiming, the son of the local deputy police chief. In recent years, road casualties caused by China’s ‘second-generation rich’ (fu erdai 富二代, the progeny of the wealthy, often with powerful Party connections) have outraged ordinary citizens because of the leniency normally shown to the culprits. When campus security guards arrested Li, he shouted: ‘Go ahead, charge me if you dare, my dad is Li Gang!’ Netizens promptly inundated the Internet with parodies and permutations of ‘My dad is Li Gang!’ (Wo ba shi Li Gang! 我爸 是李刚!) lambasting the abuse of power among China’s rich. State censors tried to contain the public reaction by blocking reports about the incident but it proved too irresistible, even for CCTV (China Central Television). On 21 October, the national broadcaster aired an interview with a tearful Li Gang, who apologized on his son’s behalf. The next day a report featured a weeping and contrite Li Qiming; he was later sentenced to six years in gaol. Before the case was heard in court, Li’s father paid 466,000 yuan (US$73,750) as compensation to the dead girl’s family and 91,000 yuan (US$14,400) to the injured girl, with half this sum being payment for her hospital treatment.

An Internet joke that circulated following the ‘My Dad is Li Gang!’ incident showing a road sign Photoshopped to read: ‘Friend: Drive slowly, your dad is not Li Gang!’

Source: Hudong.com

In January 2011, when the official Xinhua News Service released its 2010 list of ‘Top Ten Buzzwords on the Internet in China’, ‘My dad is Li Gang’ was ranked number four and stood out as the only politically sensitive catchphrase. The fact that it was listed at all indicates something of a new willingness to heed the simmering discontent about the wealth gap.

The inequality now affecting every aspect of Chinese society has lent particularly ambivalent impetus to the revival of ‘red culture’. Given rampant official corruption, the Maoist rhetoric of egalitarianism, minus its original anti-capitalist tenor, has popular appeal while justifying the continuation of one-party rule. Egalitarian rhetoric was the staple fare of a much poorer China where political campaigns and ideological witch-hunts co-existed with dreams of national prosperity. Back then the Communist Party enjoyed a monopoly on defining what was ‘red’. In the digital present-day, ordinary netizens and the Party elite alike can contend among themselves and with each other over the true value and utility of Maoist ideas and ideals.

In the weeks that followed the removal of Bo Xilai from all of his official positions on 15 March 2012, the Party leadership in Beijing held back from pronouncing on the ‘red’ campaigns that were Bo’s trademark from 2009. Still, on the eve of Bo’s dismissal on 14 March 2012, Premier Wen Jiabao, a known opponent of Bo, delivered a widely noted speech (discussed in the introduction to this volume). In it he called for renewed efforts at political reform to safeguard against the recurrence of a ‘historical tragedy on the scale of the Cultural Revolution’. Wen’s remarks were a barely veiled attack on Bo, whose flaunting of ‘redness’ tacitly accused his critics of being less than genuine socialists. To forestall speculation about factional strife in the Party’s upper echelons, the state’s Publicity Department (formerly known as the Central Propaganda Department) soon issued a directive forbidding mainland news outlets from publishing extended commentaries on the Premier’s speech.

The Chinese party-state generally prefers to stress its socialist credentials while downplaying its Maoist origins. A highly publicized People’s Daily editorial of 11 April 2012 urged Chinese citizens to ‘maintain a high level of ideological unity’ with the Politburo in Beijing and to ‘raise high the great banner of socialism with Chinese characteristics’. The editorial was at pains to reassure its readers that ‘China is a socialist country ruled by law’ in which ‘there is no privileged citizen before the law’. Such grandiose if content-free declarations together with zealous state censorship and state-sponsored rumours meant that Chinese Internet coverage of the unfolding drama around Bo, his wife Gu Kailai and their coterie was highly restricted and monitored, not to mention biased against the purged Bo. Yet, the politically engaged were just as determined to publicize their views on this issue as the state censors were to suppress them. And so yet again, irrepressible coded debate continued to thwart any official hope for ‘ideological unity’.