Li Changchun — a member of the Communist Party’s ruling Politburo Standing Committee — declared in March 2007 that China should develop a Harmonious Society based on ‘core socialist values’ (shehuizhuyi hexin jiazhi tixi 社会主义核心价值体系). Party ideologues explained these values in a press release that expanded on Li’s comments:

Marxism is the leading theory, while Socialism with Chinese Characteristics is the common goal. A nationalist spirit founded on patriotism and a public spirit based on reform and innovation should be developed, and the core socialist values should also incorporate a socialist concept of honour and disgrace … .

The values that Li outlined in his speech are often contrasted with ‘universal values’ (pushi jiazhi 普世价值), such as the concepts of human rights and basic freedoms. Although government officials generally dismiss universal values as coming from the West or for being promoted by liberal publications and liberal intellectuals calling for political reform, they occasionally acknowledge that they also have a place in China. In 2007, although he did not use the term ‘universal values’, then Premier Wen Jiabao wrote that ‘science, democracy, rule of law, freedom and human rights are not unique to capitalism, but are values commonly pursued by mankind over a long period of history’. His comments, however, did not receive public endorsement by other top leaders.

Since 2008, a debate on the two value systems has once more unfolded in the Chinese press. Like many other aspects of civilising China that feature in this book, the discussion harks back to ideological contestations that began in the late nineteenth century. Before the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, China’s Communist Party leaders committed themselves to creating a new democratic China that would champion equality, human rights and economic prosperity — all of which they accused the previous Nationalist Party government of failing to realise. Soon after 1949, however, Mao Zedong and his comrades established a political system that featured very particular definitions of democracy and human rights: the former, for example, was equated with ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’ and the latter included the ability to rise from poverty but not freedom of expression. Then, in the 1950s, a series of ideological purges were aimed at eliminating support for the kinds of Western political and cultural values that were now seen as a threat to China’s unique form of socialism.

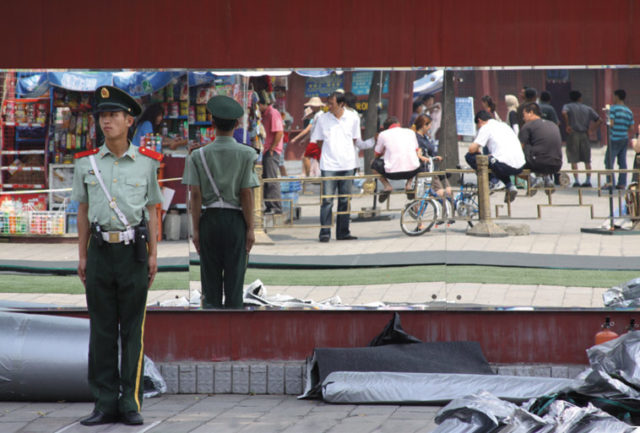

In the ongoing clash of civilisations in China itself — between the Marxist–Leninist party-state and its values, and the advocates of Western-inspired universal values — the party-state typically couches its arguments in language first developed in the Soviet Union and the early years of the People’s Republic. In 1983, when Deng Xiaoping’s five-year-old policy of Reform and an Open Door to the outside world had seen a rise in free-thinking in the universities and among influential cultural figures, the Party launched the Anti-Spiritual Pollution campaign. As in other ideological purges, the campaign promoted a vision of socialist-Chinese spiritual civilisation that included mundane details of social behaviour (no spitting) as well as ideological ideals (no ‘misty’ or politically ambiguous poetry and definitely no ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ that would champion electoral democracy and free speech) and that, in its broadest form, continues to hold sway in China today.

Yet the abiding contradiction between the domestic priorities of the one-party state, what we call ‘official China’, and its desire to be a respected and integrated member of the international community generates friction not only with the outside world (which can react with outrage, for example, at the imprisonment of dissidents and human rights abuses), but also within the People’s Republic itself. As Chinese society evolves and its middle class burgeons the debate over values continues and grows. As we have seen in this Yearbook, a major focus in 2013 has been constitutional governance. Issues to do with government accountability, independent legal oversight of politics and the economy, media freedom and individual rights will not go away anytime soon.

As in the late nineteenth century, independent Chinese cultural figures and thinkers judge the level of China’s civilisation by standards that may be at odds with the ones of those in power. When, in early 1989, some liberal thinkers agitated for political change in the prelude to what became a nationwide protest movement, the poet Bei Dao wrote:

Capitalism has no monopoly on the protection of human rights and freedom of speech; they are the standard of any modern, civilised society.

I believe every Chinese intellectual realises how extremely tortuous China’s path to Reform is. However, during this process, the rulers must become accustomed to hearing different, even discordant, voices. It is beneficial to develop such a habit; it will mark the beginning of China’s progress toward becoming a modern and civilised society.

Complicating the debate about clashing values systems are issues of patriotism and loyalty, which are particularly relevant in China’s restive borderlands. During the Lhasa riots of April 2008 Chang Ping asked in a Southern Metropolis Daily editorial: ‘If we use nationalism as a weapon to resist Westerners, then how can we persuade the ethnic minorities to abandon their own nationalism and join mainstream nation-building? Apart from the official government position, will the media be permitted to discuss the matter freely and uncover more truths?’ Given that the spectre of ethnic separatism (labelled ‘splittism’) is a major political bugbear, the editorial, not surprisingly, attracted heavy criticism online for its seemingly ‘traitorous’ tone. Soon after, Wen Feng (an alias) wrote an op-ed for the Beijing Evening News in which he accused Chang Ping’s editorial of playing fast and loose not only with the facts but also of abnegating moral responsibility. Wen also criticised Chang for holding values in which ‘only things of the West are universal and need to be upheld’.

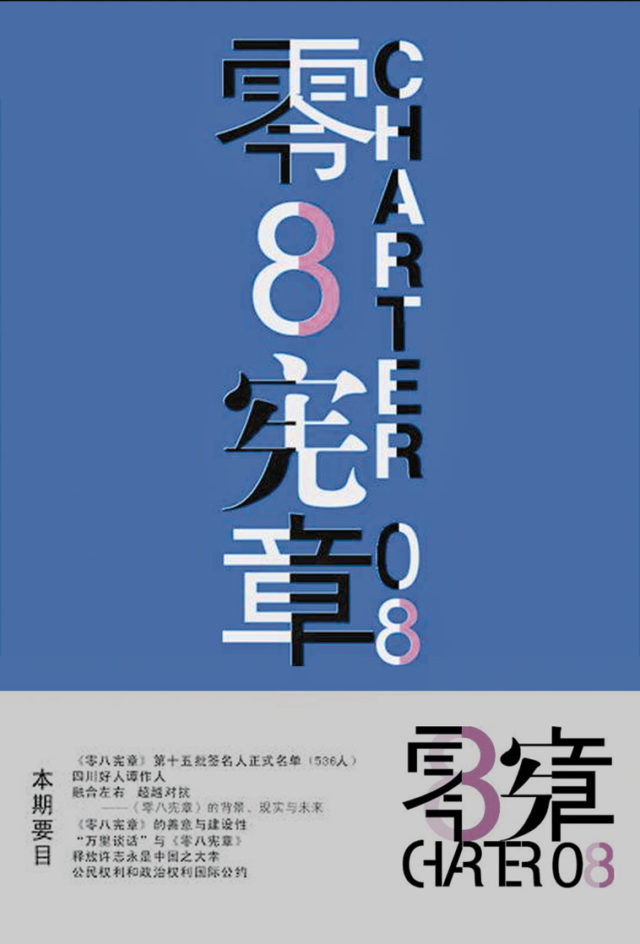

The following month, editors at the Southern Weekly waded into the debate, praising the government’s response to the Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan for respecting ‘universal values’. Like Chang Ping’s editorial for the Southern Metropolis Daily, this editorial attracted allegations of traitorous attitudes from conservative groups who read any advocacy of universal values as a Western plot to undermine the Communist Party. The controversy re-emerged during the August 2008 Beijing Olympics. The official slogan of the Games was clearly universalist: ‘One World, One Dream’. Conservative commentators skewered the slogan. Dissidents and liberal academics, on the other hand, published ‘Charter 08’ — a manifesto supporting universal values — under the aegis of the well-known writer (and now jailed Nobel Peace Prize laureate) Liu Xiaobo.

In his report to the Eighteenth Party National Congress in November 2012, however, President Hu Jintao spoke about ‘universal values’ and ‘core socialist values’ without conveying any sense that there might be a contradiction between the two. As Hu put it, one of China’s development goals is to ‘constantly increase the credibility of the system of justice, and to effectively respect and protect human rights’ (sifa gongxinli buduan tigao, renquan dedao qieshi zunzhong he baozhang 司法公信力不断提高,人权得到切实尊重和保障). Hu went on to say that democracy, freedom, equality, justice and rule of law (minzhu, ziyou, pingdeng, gongzheng, fazhi 民主、自由、平等、公正、法治) were to be ‘encouraged’ (changdao 倡导), after which he went on to reiterate the need for an ‘active cultivation of socialist core values’ (jiji peiyu shehuizhuyi hexin jiazhiguan 积极培育社会主义核心价值观).

Speaking at a National Thought Work Conference on 20 August 2013, the new party leader Xi Jinping reiterated the importance of ‘core socialist values’ and a tireless struggle to maintain ideological unity in the face of a rapidly changing world. China’s economic achievements and relative social cohesion at a time of continued global uncertainty, he said, give the Party reason to celebrate its successes and persevere on its chosen path. As it does so, Xi emphasised, the Party needs ‘to tell the China story well, to make sure China’s voice is heard’ internationally (jiang hao Zhongguo gushi, chuanbo hao Zhongguo shengyin 讲好中国故事, 传播好中国声音).

Such triumphalism masks the fact that there is an abiding clash of cultures within the Chinese Communist Party itself. Its strict materialist worldview precludes any endorsement of abstract human worth and universal value. But, rhetorically at least, it recognises the potentially positive role of values that, like Marxism itself, first evolved in the West. Some within the party-state don’t see these as mutually exclusive. In Chapter Four, Jiang Bixin, Deputy Chief Justice of the Supreme People’s Court, is quoted as saying:

Concepts such as democracy, freedom, equality, rule of law, justice, integrity, and harmony should be incorporated into core socialist values … . These concepts have never been merely patents of the bourgeoisie, but are the product of the civilising process which is commonly created by all human beings.

Perhaps it is in similar embrace of both socialist and universal values that legal and party thinkers will discover a third theoretical way forward — one that affirms the achievements of the Party while also allowing for it to moderate its ideological stance to fit the increasingly sophisticated demands of its people as part of its own civilising process.