Image: The National Centre for the Performing Arts (‘The Egg’), Beijing

Source: Gustavo Madico/Flickr

In April 2014, an article titled ‘The China Dream and the New Horizon of Sinicised Marxism’ appeared on the Qiushi 求是 website run by the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee. Qiushi describes itself as the Party’s ‘most influential and most authoritative magazine devoted to policy-making and theoretical studies’ and aims to promote the Party’s ‘governing philosophy’. The article defined the China Dream as the ‘means for bringing together the state, the nation and individuals as an organic whole’. It can do this, the article said, because it ‘accentuates the intimate bond between the future and destiny of each and every person with that of the state and nation’.

In 2013, other articles in the state media tied the notion of the China Dream to the catchphrase of Shared Destiny, describing the China Dream itself as a Community of Shared Destiny (distinguishing itself from the American Dream of individual freedom). According to an earlier article published by the state news agency Xinhua, this is a community ‘in which the interests of nation and state and the interests of each and every person become intricately linked, such that when people are encouraged to establish their own ideals, they also create the conditions for everyone else to realise their ideals’.

These long-winded formulations are a product of what China’s party leaders, and the party theorists who help write their speeches, call tifa 提法: ‘formulations’, or correct formulas for the expression of key political or ideological concepts. Intentionally vague and circular statements, these formulations are an essential part of China’s official language because they can be made to fit a wide variety of situations. Phrases like ‘to link one’s personal future and destiny with the nation and state’s future and destiny’ are word-strings, designed for repetition, like a pledge or a mantra of intellectual fealty.

Formulations/Tifa

The Party’s leaders and theorists are the keepers of a language that is designed to guide people’s actions and thoughts while reinforcing the notion of one-party rule as China’s historical destiny. Many of these didactic formulations have the authority of scripture. But while the party’s rhetoricians must employ standard, revered and authoritative formulations in the Party’s lexicon, they cannot rely on repetition alone as the old formulations do not always stretch to cover new circumstances, answer fresh challenges or express refinements of ideology. In order to establish themselves as unique contributors to China’s advancement, and secure their place in history, the leaders and theorists thus seek to develop new tifa within the constraints set by the diction and vocabulary of their predecessors. The way they refine the concept of Shared Destiny, for example, will determine their future place in history as well as their careers and livelihood in the present day.

In 2013–2014, as Xi Jinping’s new administration sought to rein in corruption and pollution, redress inequalities and reform the law, it cautiously updated the official language. It employed words like ‘destiny’, ‘history’ and ‘mission’ to lend Xi’s leadership an image of strength and boost the legitimacy of one-party rule.

As noted in the China Story Yearbook 2013, China’s former president and party general secretary Hu Jintao was prone to overuse impersonal tifa in his speech, for which he was widely parodied in Weibo posts that told him to ‘speak like a human being’. Xi Jinping, by contrast, initially attracted praise for being plain-spoken, part of his carefully cultivated image as a ‘man of the people’.

Rumours and Big Vs

By August 2013, when Xi showed himself to be even less tolerant of dissent than his predecessor, the praise gave way to pensive silence. That month, his administration launched a fresh, strict crackdown on online ‘rumours’ with the arrests of Charles Xue 薛必群 and Wang Gongquan 王功权, wealthy venture capitalists and microbloggers who had carved out a big presence on the Internet with their liberal views and enthusiastic support for a range of social causes. Xue and Wang were ‘Big Vs’ — a term used to describe popular microbloggers with verified (V) real-name Weibo accounts and whose followers numbered in the millions.

Hu Jintao began the campaign against ‘rumours’ in 2012 under the pretext of protecting the public from fake news, but Xi has pursued it vigorously. The detention of Xue, Wang and others, and their abject televised confessions (see Forum ‘Orange as the New Black’, p.316) showed Xi’s determination to guide and contain public discourse. Although the detainees received plenty of messages of support from outside China, the Party effectively demonstrated that even ‘Big Vs’ posed no threat to its power. Xue had more than twelve million Weibo followers before his account was shut down and Wang 1.5 million. Their public humiliation cowed many other ‘Big Vs’ as well as less prominent and well-financed netizens into self-censorship and silence.

Ideology Recalibrated

For all their ‘anti-rumour mongering’ rhetoric, China’s Party leaders are experts at using innuendo to keep people guessing and uncertain. A case in point is the address that Xi gave on 19 August 2013 to propaganda officials at the National Ideological Work Conference in Beijing (noted in our 2013 Yearbook), which state media reports promptly trumpeted as his ‘important speech of 19 August’ without revealing its detailed contents. In the weeks that followed, numerous editorials and commentaries about Xi’s ‘important speech’ appeared in key party newspapers and websites but only broadly hinting at its content: articles in the People’s Liberation Army Daily and China Youth Daily on 21 August and 26 August, for example, mentioned ‘positive propaganda’ and ‘the struggle for public opinion’.

In November, an unverified document purporting to be a leaked transcript of the speech began circulating on the Internet. Independent commentators posting on websites hosted outside China were confident that the document was genuine because its content reflected what had been said about the speech in party publications that had appeared in the intervening months.

To date, the full official text of Xi’s speech has not been made public and the authorities have neither confirmed nor denied the leaked document’s authenticity. Instead, the state media has mainly quoted others talking about it: provincial propaganda chiefs, senior editors at leading state media organisations and senior Party officials such as Cai Mingzhao 蔡名照 (director of China’s State Council Information Office) and Liu Yunshan (who as leader of the Party’s Central Secretariat, head of the Central Party School and a member of the Politburo Standing Committee is one of China’s top seven leaders).

On 24 September 2013, Qian Gang 钱钢, Director of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong, published his analysis of the reporting of Xi’s ‘important speech’. Qian identified the term ‘the struggle for public opinion’ 舆论斗争 as the key to understanding the priority Xi placed on suppressing dissent. Qian noted that the term was a throwback to the early post-Mao period: it first appeared in a People’s Daily editorial of 1980, four years after Mao’s death and the end of the Cultural Revolution, when there was still raw and fierce debate over the legacies of both. Qian argued that whereas Xi’s administration has previously used ‘the struggle for public opinion’ to justify tighter censorship to protect mainland public culture from Western ‘spiritual pollution’, it was now also targeting critical debate within China itself.

Qian noted that the initial Xinhua report of 20 August 2013, which he said bore the marks of a ‘rigid process of examination and authorisation’, made no mention of the ‘struggle for public opinion’. The term was also missing from eight subsequent People’s Daily commentaries about Xi’s speech that appeared from 21 August onwards. Yet on 24 August, the Global Times, the jingoistic subsidiary of People’s Daily published an editorial titled ‘The Struggle for Public Opinion’, which it described as ‘an unavoidable challenge to be faced head on’ 舆论斗争,不能回避只能迎接的挑战.

After ten days of not mentioning the ‘struggle’, on 30 August 2013, the People’s Daily published a lengthy editorial that cited Xi as explicitly calling for ‘the struggle for public opinion’ so as to ‘effectively channel public opinion’. More lengthy articles followed in September promoting the idea. Qian viewed this carefully orchestrated revival of the term, occurring in tandem with the crackdown on ‘online rumours’, as a further indication that political reform was not on Xi’s agenda.

At the time of Xi’s speech, one target of ‘the struggle for public opinion’ was Bo Xilai, the ousted Party secretary of Chongqing whose trial, held from 22 to 26 August, had engrossed the nation (see the China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China). Xi Jinping had previously supported Bo’s ‘Red’ revival (see the China Story Yearbook 2012: Red Rising, Red Eclipse) and had praised his ‘strike black’ anti-crime campaign. By late August 2013, Bo had to be denounced as a corrupt official who deserved life imprisonment. No mention was to be made of his once-enormous popularity or Xi’s former support.

From September through October, ‘the struggle for public opinion’ acquired a distinctive diction. The revived Mao-era term Mass Line 群众路线 was now often married to the moral posture ‘with righteous confidence’ 理直气壮地 to form sentences such as: ‘To proceed with righteous confidence and properly carry out the Mass Line Education and Practice Campaign’ 理直气壮地做好群众路线教育实践活动. Launched in June 2013, this campaign grew more intense two months later with the media offensive around Xi’s 19 August speech (see the China Story Yearbook 2012: Red Rising, Red Eclipse, Chapter 3 ‘The Ideology of Law and Order’, p.60).

Unsheathing the Sword

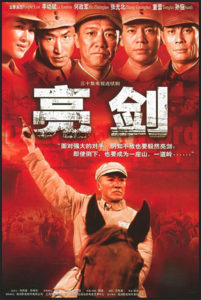

Of all the slogans associated with ‘the struggle for public opinion’, the most striking is ‘Dare to grasp, control and unsheathe the sword’ 敢抓敢管敢于亮剑 (see Chapter 6 ‘The Sword of Discipline and the Dagger of Justice’, p.260). This phrase first appeared, without attribution, in two commentaries published on 2 September 2013 in both the People’s Daily and Beijing Daily respectively. In an article published on 30 September on Deutsche Welle’s Chinese-language website, the Beijing-based democracy activist Chen Ziming 陈子明 likened ‘the struggle for public opinion’ and ‘unsheathe the sword’ to Chairman Mao’s strategic pairing of ‘class struggle’ and ‘don’t fear poisonous weeds’ at the Party’s National Thought Work Conference in 1957 that signalled the start of the Anti-Rightist Campaign: ‘precious words dictated from on high, with a unique and mutually sustaining significance’.

Yet in 1957, ‘class struggle’ was a political theory elevated to a doctrine of mass mobilisation. ‘Poisonous weeds’ was Mao’s metaphor for dissent in the garden of true Communism. In 2013, ‘the struggle for public opinion’ was a more nebulous idea and ‘unsheathe the sword’ 亮剑 came from a hit TV series of the same name.

The Shanghai-based entertainment company Hairun Pictures co-produced the TV series Unsheathe the Sword with a unit of the PLA. Set in the wartime China of the 1930s and 1940s, it was based on the novel by Du Liang, a former PLA soldier. China’s most-viewed TV series in 2005, it has enjoyed frequent reruns. The title comes from a line spoken by the show’s protagonist, Li Yunlong, a PLA general: ‘When you’re faced with a mighty foe and you know you’re not his match, you must be resolute and unsheathe your sword. If you’re cut down, become a mountain, a great mountain ridge!’

Fans of Unsheathe the Sword praised its unvarnished portrayal of human foibles in the time of war. As Geng Song 宋耕 and Derek Hird have written, Li, ‘depicted as a crude man with a bad temper and a foul mouth’ was a startling departure from the revolutionary screen heroes of the Maoist period. Cunning, rebellious and fond of drink, he more closely resembled ‘the knight-errant’, an outlaw archetype of popular Chinese culture (epitomised in the Ming-dynasty novel Outlaws of the Marsh). ‘Unsheathe the sword’ became urban slang in 2005, signifying manly daring in the pursuit of one’s goals.

Unsheathe the Sword was such a success that, on 16 November 2005, the state’s China Television Art Committee and the PLA’s publicity department ran a symposium on the show in the hope of finding a winning formula for future party- and nation-building ventures in popular entertainment. While the unverified transcript of Xi’s speech contained the expression ‘dare to grasp, to control and to unsheathe the sword’, by linking it to the ‘stability maintenance’ campaigns against crime, corruption, dissent and terrorism he distorted its meaning. Still, those keen to show there is no need to struggle for their opinion readily adopt the Party’s usage, describing Xi as having ‘unsheathed his sword’ when he met with US Vice-President Joe Biden to discuss China’s Air Defence Identification Zone in December 2013, for example, or when he launched the probe into the corrupt affairs of China’s former propaganda chief Zhou Yongkang 周永康 (see Information Window ‘Big Game: Five “Tigers” ’, p.266).

Back to Nature

The unverified transcript of the 19 August speech also shows Xi calling for renewed attention to the ‘relationship between the nature of the Party and the nature of the people’. The ‘nature of the Party’ is described as ‘wholehearted service to the people’ in the form of ‘a Marxist political organisation that is of and for the people’. The transcript highlights the importance of Party officials not alienating the people. Understanding the ‘nature of the people’ means heeding the different ‘ideological and cultural needs’ of different groups: ‘workers, peasants, PLA soldiers, cadres, intellectuals, the elderly, the young, children’ as well as new group identities such as ‘the ant-tribe’ 蚁族 (college-educated, low-income workers living in city slums); ‘northward drifters’ 北漂 (job-seeking college graduates from the south living in Beijing); ‘returned students’ 海归 (the term is a homophone for ‘sea turtles’, referring to people with overseas qualifications); ‘unemployed returned students’ 海待 (the term sounds like ‘seaweed’); and ‘small investors’ 散户 (literally, ‘scattered households’).

As illustrated by the use of such terms, ideological work under Xi includes incorporating urban slang into the Party’s vocabulary as a concrete demonstration of the Party’s closeness to and understanding of the ‘nature of the people’. But it also requires the study of texts that include the speeches of former party leaders and new works produced by party propagandists such as Five Hundred Years of World Socialism (discussed below). This is ideological recalibration, as opposed to new thinking, backed up by policing ‘the struggle for public opinion’ by cracking down on ‘rumours’, for example.

We can only guess at the extent to which the crackdown on ‘rumours’ contributed to the nine percent drop in Weibo users by the end of 2013 (a loss of 27.83 million users, according to official figures). Many Weibo users migrated to Weixin (WeChat), a mobile text and voice messaging service that itself fell under close scrutiny in 2014. Although it lacks Weibo’s broad reach, Weixin nonetheless enables independent discussion of social problems by groups around the country (and abroad).

Scripting Destiny

Inequality has always dogged China’s one-party system, as unaccountable political power under Mao in the form of a revolutionary virtuocracy (to borrow Chinese politics expert Susan Shirk’s insightful phrase), then as unaccountable wealth under Deng Xiaoping and his successors in the form of a kleptocracy (to use The New Yorker’s former Beijing correspondent Evan Osnos’s description). The gap between its ideology and practice poses a challenge to the party-state. But a greater challenge comes from the fact that Chinese citizens are, in ever increasing numbers, culturally, politically, academically and socially engaged with the world beyond the control of China’s rulers. Moreover, the world — including global virtual communities of shared interests, the international media, environmental and rights activists and organisations — is engaging right back.

In June 2014, both the neo-Maoist Utopia website and Qiushi re-posted a Weibo post by the self-styled Maoist Yin Guoming 尹国明 in which he likened public intellectuals 公知 and the democracy movement 民运 to an ‘evil cult’. In China, the term ‘public intellectuals’ often signifies writers, academics and others who engage in public discourse that has not been sanctioned by the Party. Yin claimed that some who identified as such, or as democracy activists, had links to terrorist groups or banned religious organisations (‘evil cults’ in the official vocabulary) such as the controversial Church of Almighty God 全能神教会 (see Forum ‘Almighty God: Murder in a McDonald’s’, p.304). Qiushi included a disclaimer saying that the views expressed were those of the author and that Qiushi had not verified these claims.

That Qiushi was prepared to publish a text it acknowledged as potentially unreliable left readers in no doubt that the Party’s campaign against rumour-mongering exempted rumours that served its own purposes. Party rhetoric has become notably hostile towards ‘intellectuals’ 知识分子, defined as people with university qualifications in general and academics and writers in particular, from 2013. In his day, Mao had been suspicious of intellectuals, and made them a target of both the 1957 Anti-Rightist campaign and the Cultural Revolution. One of the greatest political and cultural shifts of the early post-Mao era was the ‘rehabilitation’ of China’s intellectuals and the affirmation of their importance to a modernising and economically reforming China. In his 19 August speech, Xi said that ‘to do ideological work well, the highest degree of attention must be given to the work of intellectuals’. How they fare, however, depends on how closely they identify with Xi’s Community of Shared Destiny.

As noted in the China Story Yearbook 2013, in the first half of 2013, the state banned discussions of constitutionalism and enumerated ‘Seven Things That Should Not Be Discussed’ in university courses (universal values, freedom of the press, civil society, civil rights, historical mistakes by the Party, Party-elite capitalism and judicial independence). In October 2013, Peking University terminated the appointment of Xia Yeliang 夏业良, an associate professor of economics, on the grounds of ‘poor teaching’, though online many commentators alleged that he was sacked for advocating constitutionalism. Then, in December, Shanghai’s East China University of Political Science and Law fired Zhang Xuezhong 张雪忠, a lecturer in the university’s law school, for breaching university regulations by using the university’s email system to notify colleagues of his new e-book, New Common Sense: The Nature and Consequences of One-Party Dictatorship. He too had defied the ban on discussing constitutionalism in class. The university accused him of ‘forcibly disseminating his political views among the faculty and using his status as a teacher to spread his political views among students’. Later that month, Chen Hongguo 谌洪果 of Xi’an’s Northwest University of Politics and Law stated on Weibo that the new restrictions made academic life untenable for him; he was resigning.

Many academics outside China praised these three outspoken individuals for standing up for academic freedom. They expressed concern about the limitations and long-term ramifications of collaborating with Chinese universities on research and teaching. In China, however, some colleagues cast aspersions on the academic credibility of the trio. Yao Yang 姚洋, an eminent economist based at Peking University, for example, told the online Inside Higher Education that Xia Yeliang’s publications did not meet the university’s research standards and that Xia was ‘trying to use external forces to try to force the university to keep him’. Yao commented, ‘I think that’s a really bad strategy’.

By contrast, the state has awarded generous research grants to academics whose work shows the party-state’s ideas, policies and slogans in a positive light. In November 2013, the Berkeley-based website China Digital Times (blocked in China) alerted readers to a list, announced five months earlier, of the top fifty-five major grants awarded under China’s National Social Science Fund. The fund is the nation’s most prestigious grant scheme, and is supervised by the Party’s Central Propaganda Department. The first three titles on the list were: ‘Research into reinforcing confidence in the path, theory and system of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ 坚定中国特色社会主义道路自信、理论自信、制度自信研究; ‘Research on the internal logic and historical development of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics as a body of theory’ 中国特色社会主义理论体系的内在逻辑与历史发展研究; and ‘Research into the basic requirements for seizing new victories for Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ 夺取中国特色社会主义新胜利的基本要求研究.

In February 2014, the media widely celebrated the publication of Five Hundred Years of World Socialism 世界社会主义五百年, an account by party theorists of Chinese socialism within the international context. The book, published by the Central Propaganda Department’s Study Publishing House on 1 January 2014, is now required reading for all Party cadres and members. In the ‘struggle for public opinion’ in academic circles at least, the party-state is winning.

Mixed Metaphors

Xi Jinping has used a Community of Shared Destiny in two ways. Initially, he evoked the image of a strong and prosperous nation living happily under party rule — the ‘China Dream’. Later, he extended it to describe China’s foreign policy. In his speech of 25 October 2013 in Beijing at the Workshop on Diplomatic Work with Neighbouring Countries, Xi highlighted the importance of reassuring the world that ‘the China Dream will combine with the aspirations of the peoples of neighbouring countries for a good life and the hopes of all for regional prosperity so that the idea of a Community of Shared Destiny can take root among our neighbours. Implicit in Xi’s statement is the assumption that others must adapt their national stories and dreams to those of China.

On 24 October 2013, Xu Danei 徐达内, the Shanghai-based columnist for London’s Financial Times, posted an article titled ‘A Community of Shared Destiny’ in his online column ‘Media Notes’. By sheer coincidence, on the eve of Xi’s foreign policy speech, Xu used the phrase to describe a camaraderie born of hardship among Chinese journalists. He highlighted the plight of Chen Yongzhou 陈永州, a novice reporter arrested on defamation and slander charges for investigative articles he had written about the Changsha construction company Zoomlion. Chen’s employer, the Guangzhou-based New Express 新快报, had stood by him. The paper ran a front-page banner headline on 23 October with the call ‘Release Him’ 请放人 under which appeared a front-page editorial defending Chen’s integrity and criticising the arbitrary use of police power in Changsha to arrest him. This unusually bold step taken by the newspaper’s senior executives had been Xu’s inspiration.

Two days later, however, on 26 October, China Central Television news aired a public confession by Chen, prompting the New Express to publish a retraction the following day, in which the editors apologised for questioning the police investigation and ‘damaging the credibility of the press’. With Guangzhou’s third largest media organisation thus brought into line, the government continued to widen its crackdown on ‘rumours’ in the early months of 2014 (see Chapter 3 ‘The Chinese Internet: Unshared Destiny’, p.106).

The key to understanding the ‘struggle for public opinion’ is that there is no struggle. The term warns people that they disagree with the state at their peril. In 1980, Deng Xiaoping famously used the expression ‘the Hall of the Monologue’ 一言堂 to criticise Mao for monopolising party discourse. The term is a direct critique of the Cultural Revolution concept of ‘monolithic leadership’ 一元化领导, which in 1969 was formally defined as ‘putting Mao Zedong Thought in command of everything’.

In the 1980s, Deng sought to strengthen collective leadership by appointing his protégés Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang to key positions while remaining all-powerful even in ‘retirement’. The reiteration of Xi’s ‘important speech of 19 August’ (and many of his other speeches since then) in commentaries, editorials and reports produced by others similarly projects a picture of consensus and commitment to policies that are guided in fact by one powerful person. In this sense, Xi’s emphasis on ‘the struggle for public opinion’ attempts to recover the prestige the Party enjoyed during the halcyon early years of ‘reform and opening up’ before corruption set in, and public discontent led to the massive protest movement of 1989 (see Chapter 6 ‘The Sword of Discipline and the Dagger of Justice’, p.260, and Forum ‘Xu Zhiyong and the New Citizens’ Movement’, p.292).

The party-state led by Xi seeks to repair the Party’s relations with the people using a rhetoric that combines intimidation and cultural appeal — but not just pop cultural appeal. Xi is fond of quoting from the Chinese classics and the state media enjoys presenting him as a man of erudition (see Forum ‘Classic Xi Jinping: On Acquiring Moral Character’, p.4). On 8 May 2014, the overseas edition of the People’s Daily published a full-page article, widely reproduced since, on thirteen literary allusions that Xi has used in his speeches since becoming president and party general secretary: ‘Self-Cultivation through Learning: Famous Classical Quotations by Xi Jinping’ 习得修身: 习近平引用的古典名句. Xi’s surname 习 means to study or practise; the headline puns on this to equate Xi with learning itself.

However, puns and even the most agile rhetoric cannot solve many of the key challenges facing the party-state. In an article published on 27 March 2014 on the bilingual website China Dialogue, Beijing-based environmental and legal consultant Steven Andrews wrote that the Chinese government’s Air Quality Index, which is less stringent than international standards, caused China’s pollution to be reported ‘in a misleading way, blocking public understanding and enabling official inaction’. Another example is the enforcement of the ideal of ‘maintaining a unified approach’ 统一口径 in news coverage, when it has often been independent investigative journalists who have exposed many serious problems, especially those related to corruption in local areas. The second half of the phrase in Chinese, 口径 (pronounced koujing) signifies the calibre or bore of a gun, which lends the phrase the sense of a line of matched guns all firing in unison.

Say ‘Uncle’

Big Daddy Xi — ‘Photoshopped’ images of President Xi holding a yellow umbrella were used at various pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. The political meme went viral on social media

Source: hkfuture2047.wordpress.com

Yet while Xi’s vision of Shared Destiny involves a tightening of central control, his administration also demonstrates a savvy approach to image management. Since the latter half of 2013, large numbers of non-official pro-Party online comments have appeared referring with casual (but respectful) familiarity to Xi Jinping as Xi zong 习总 (‘Gen Sec Xi’), Xi laoda 习老大 (‘Eldest Brother Xi’) and even Xi dada 习大大 (‘Uncle Xi’). Whether or not Party propagandists came up with these forms of address, the censors appear happy to allow — if not encourage — them to circulate.

A widely relayed Southern Weekly article of 24 April 2014 on ‘appropriate uses of honorifics in officialdom’ notes that standard honorifics are frequently complicated by local variations. ‘Eldest brother’ 老大, historically signifying the head of a martial arts clan or band of knights-errant, implies a leader among men, one who commands personal loyalty — the cardinal virtue in martial arts folklore. The friendly abbreviation of the top Party position to zong (more commonly used as an abbreviation for ‘manager’ in businesses and organisations) is used far more frequently of Xi than his predecessors. Dada, meaning paternal uncle, bespeaks familial affection.

These informal honorifics that elevate Xi to a folkloric hero, national manager and beloved patriarch are a new development in the sphere of ideological work. By ‘unsheathing the sword’, the party-state under Xi has cut through an official language hidebound by precedents to establish a Community of Shared Destiny. Yet the Chinese word for destiny, mingyun 命运, can also mean ‘fate’ (see Information Window ‘Mingyun 命运, the “Destiny” in “Shared Destiny” ’, p.xii).

Whereas destiny foretells a happy end, fate can progress to gloom and doom. The official interpretation of mingyun, however, in this case, excludes ‘fate’ — in the rhetoric of the party-state, destiny can only be positive.

Notes

‘About Qiushi Journal’, Qiushi Journal, 19 September 2011, online at: http://english.qstheory.cn/about/201109/t20110919_110860.htm

‘The China Dream and the New Horizon of Sinicised Marxism’ 中国梦与马克思主义中国化的新境界, Qiushi Journal, 23 April 2014, online at: http://www.qstheory.cn/hqwg/2014/201408/201404/t20140423_343089.htm. The article first appeared in Red Flag Manuscripts 红旗文稿, an offshoot of Qiushi Journal and a leading outlet for the publication of Party theory and ideas and policies of the moment.

Zhang Ji 张纪, ‘The China Dream: to form a community of shared destiny for all of humanity’ 中国梦:铸就人类命运共同体, Xinhua, 1 November 2013, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2013-11/01/c_125636138.htm. The definition of a ‘community of shared destiny’ in this article (first published in the Party journal Party Construction 党建) was provided by Cong Bin, Vice-Chairman of the Central Committee of the Jiusan Society (‘September Third Society’), one of eight legally recognised minor political parties under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party. In using Cong’s endorsement of the ‘China Dream’, the state media sought to demonstrate unanimous commitment to Xi Jinping’s vision. The article and Cong’ definition of the China Dream were reproduced on numerous websites.

There are numerous English-language media reports on these two arrests. See, for instance, Keith Zhai, ‘Rights advocate Wang Gongquan: latest to give video confession’, South China Morning Post, 5 December 2013, online at: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1373529/rights-advocate-wang-gongquan-latest-give-video-confession

The transcript has been posted on numerous websites including on China Digital Times, titled ‘Full transcript of Xi Jinping’s 19 August speech: in the use of language, one must dare to grasp, control and unsheathe the sword’网传习近平8•19讲话全文:言论方面要敢抓敢管敢于亮剑, http://chinadigitaltimes.net/chinese/2013/11/%E7%BD%91%E4%BC%A0%E4%B9%A0%E8%BF%91%E5%B9%B38%E2%80%A219%E8%AE%B2%E8%AF%9D%E5%85%A8%E6%96%87%EF%BC%9A%E8%A8%80%E8%AE%BA%E6%96%B9%E9%9D%A2%E8%A6%81%E6%95%A2%E6%8A%93%E6%95%A2%E7%AE%A1%E6%95%A2/

Cai Zhaoming蔡名照, Tell China’s Story Well, Spread China’s Voice Well’ 讲好中国故事, 传播好中国声音, People’s Daily, 10 October 2013, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1010/c1001-23144775.html. An English translation is available at http://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2013/10/10/chinas-foreign-propaganda-chief-outlines-external-communication-priorities/. Liu Yunshan has made a point of quoting from Xi’s speech in several of his own speeches since August 2013. See for example, his speech on 3 January 2014, reported in Xinhua, ‘In Beijing, the National Conference of Propaganda Chiefs has started: Liu Yunshan demands even greater initiative and enthusiasm in all areas of work’ 全国宣传部长会议在京召开:刘云山要求更加积极主动奋发有为做好各项工作, Xinhua, 3 January 2014, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2014-01/03/c_118826462.htm

Qian Gang, ‘Parsing the Public Opinion Struggle’, China Media Project, 24 September 2013, online at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2013/09/24/34085/

Xi visited Chongqing in December 2010. See, for example, Liu Yawei, ‘Bo Xilai’s Campaign for the Standing Committee and the Future of Chinese Politicking’, China Brief Vol. 11 No. 21 (11 November 2011), available at http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=38660&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=517#.U_VBG_mSxfc

Gong Litang 龚立堂, ‘“Cognition, Strategy, Effect”: an analysis of the Party’s promotion of its Mass Line Education and Practice Campaign’ 认知•策划•效应:党的群众路线教育实践活动宣传探析, The Press 新闻战线, 1 September 2013, online at: http://paper.people.com.cn/xwzx/html/2013-09/01/content_1393464.htm

Chen Ziming 陈子明, ‘“The Struggle for Public Opinion” and “Daring to Unsheathe the Sword”’ ‘舆论斗争’ 与 ‘敢于亮剑’, 6 October 2013, online at: http://chenziming2013.blog.sohu.com/279517208.html

In Chinese: 面对强大的对手,明知不敌,也要毅然亮剑,即使倒下,也要成为一座山,一道岭!

Geng Song and Derek Hird, Men and Masculinities in Contemporary China, (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014), pp. 46-47

‘Transcript of the Expert Symposium on CCTV Hit TV Series Unsheathe the Sword’ 央视热播电视剧《亮剑》专家研讨会实录, Sina Entertainment 新浪娱乐, 16 November 2005, online at: http://ent.sina.com.cn/v/2005-11-16/ba898944.shtml

The popular online expression appears, among other places, in a widely circulated unattributed blog post ‘Xi Jinping “unsheathes his sword” at meeting with Biden to reaffirm China’s Air Defence Identification Zone’ 习近平“亮剑”向拜登重申识别区立场, 5 December 2013, online at: http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_4d353f020102ebjy.html

See the report (unattributed) ‘From Weibo to WeChat’, The Economist, 18 January 2014, online at: http://www.economist.com/news/china/21594296-after-crackdown-microblogs-sensitive-online-discussion-has-shifted-weibo-wechat. The figures appear in CNNIC’s January 2014 publication ‘Statistical Report on Internet Development in China’ 中国互联网络发展统计报告, CNNIC, https://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201403/P020140305346585959798.pdf

On Maoist China’s revolutionary virtuocracy, see Susan Shirk, Competitive Comrades: Career Incentives and Student Strategies in China (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982). On post-Maoist kleptocracy, see Evan Osnos, ‘Brother Wristwatch and Grandpa Wen: Chinese Kleptocracy’, The New Yorker, 25 October 2012, online at: http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/brother-wristwatch-and-grandpa-wen-chinese-kleptocracy

Yin Guoming 尹国明, ‘Why I Call the Democracy Movement an Evil Cult’ 为什么说民运也是一种邪教, reposted on Qiushi Journal, 11 June 2014, online at: http://www.qstheory.cn/politics/2014-06/11/c_1111089573.htm

Andrew Jacobs, ‘Chinese Professor Who Advocated Free Speech Is Fired’, The New York Times, 10 December 2013, online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/11/world/asia/chinese-professor-who-advocated-free-speech-is-fired.html. On the politics of these sackings, see Shi Yige, ‘The way Xi moves: speech under assault’, China Media Project, 18 March 2014, online at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2014/03/18/35037/

Yiqin Fu, ‘A “Narrowing Path” for China’s Scholars’, Tea Leaf Nation, 29 December 2013, online at: http://www.tealeafnation.com/2013/12/a-narrowing-path-for-chinas-scholars/

Elizabeth Redden, ‘Has China Failed Key Test?’, Inside Higher Ed, 21 October 2013, online at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2013/10/21/peking-u-professor-fired-whats-seen-test-case-academic-freedom#ixzz2iQ6UqC49

Anne Henochowicz, ‘Chinese Dreaming in the Ivory Tower’, China Digital Times, 1 November 2013, online at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2013/11/chinese-dreaming-ivory-tower/

CCTV News, ‘Xi Jinping’s Important Speech at the Conference on Diplomatic Work with Neighbouring Countries’ 习近平在周边外交工作座谈会上发表重要讲话, People’s Daily, 25 October 2013, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2013/1025/c1024-23331526.html

Xu Danei 徐达内, ‘A Community of Shared Destiny’ 命运共同体, Financial Times, 24 October 2013, online at: http://www.ftchinese.com/story/001053088?full=y

See the two reports by David Bandurski, ‘Paper Goes Public Over Reporter’s Detention’, China Media Project, 23 October 2013, online at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2013/10/23/34376/; and ‘Guilt and shame in China’s Media’, China Media Project, 30 October 2013, online at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2013/10/30/34446/

People’s Daily Overseas Edition, ‘Self-Cultivation through Learning: Famous Classical Quotations by Xi Jinping’ 习得修身篇: 习近平引用的古典名句, People’s Daily, 8 May 2014, online at: http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrbhwb/html/2014-05/08/content_1424711.htm. See the account by Josh Chin, ‘Literary Leaders: Why China’s President Is So Fond of Dropping Confucius’, China Real Time, 9 May 2014, online at: http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2014/05/09/literary-leaders-why-chinas-president-is-so-fond-of-dropping-confucius/

Steven Q. Andrews, ‘China’s air pollution reporting is misleading’, chinadialogue, 27 March 2014, online at: https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/6856-China-s-air-pollution-reporting-is-misleading

Ju Jing, Sun Tiantian and Yang Qiaochu, ‘The Use of Honorifics in Officialdom’ 官场‘称呼学’, Southern Weekly, 24 April 2014, online at: http://www.infzm.com/content/100108