In the first half of 2013, the new administration of Xi Jinping banned university lecturers as well as popular and academic media from discussing ‘constitutionalism’ (the notion that the Chinese government and laws must be guided by the Chinese constitution). It also instructed them not to mention the ‘Seven Speak-Nots’ 七个不要讲 (七不讲 for short): universal values, freedom of the press, civil society, civil rights, historical mistakes by the Party, judicial independence, and [the existence of the] Party-elite capitalist class 权贵资产阶级. As of early 2016, these prohibitions remained in place with one small but crucially suggestive difference—in 2015, the government began referring to the ‘Seven Speak-Nots’ as ‘Western values’.

An Opinion on Strengthening and Improving Propaganda and Ideological Work in Higher Education Under the New Circumstances

Source: chinadigitaltimes.net

An Ominous Speech

The first assault on ‘Western values’ in 2015 was on 29 January when China’s Education Minister Yuan Guiren 袁贵仁 addressed Chinese university leaders and education officials at a national meeting in Beijing. Yuan called for vigilance in ‘ideological management, especially of textbooks, teaching materials, and class lectures’. He declared an ‘absolute prohibition’ 决不允许 on: ‘textbooks promoting Western values’; ‘remarks that slander the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party or that vilify socialism’; ‘remarks that violate the country’s constitution and laws’, and ‘remarks by teachers giving vent to personal grudges or expressing discontent in the classroom, thereby transmitting all manner of unhealthy feelings to their students’. On the Internet in the Mainland, these were quickly dubbed ‘The Four Absolute Nos’, written as either 四个绝不 or 四个决不, which all universities were to observe in order to prevent the dissemination of ‘Western values’ and to secure ‘The Three Bottom Lines’ 三条底线 in the areas of politics, law, and ethics.

The Beijing forum at which Yuan spoke had been convened to discuss a document titled ‘An Opinion on Strengthening and Improving Propaganda and Ideological Work in Higher Education Under the New Circumstances’ 关于进一步加强和改进新形势下高校宣传思想工作的意见 (hereafter ‘Opinion’). This document, drafted by the General Office and the State Council of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), had been published ten days earlier. The ‘Opinion’ refined the arguments of similar directives issued during Xi’s first year in office such as the ‘Sixteen Suggestions of the Chinese Communist Party on Strengthening Ideological and Political Work among Young Teachers in Higher Education’ 中共16条意见加强高校青年教师思想政治工作, which was published on 28 May 2013.

Outside China, Yuan’s anti-Western invective drew a flood of critical responses from online and print media as well as within academia, much of it on forums like Twitter that are blocked in China. Within China itself, media censorship ensured that domestic voices critical of Yuan’s speech went largely unheard, with the notable exception of three pointed questions posted online by Shen Kui 沈岿, a professor and vice-dean at Peking University’s Faculty of Law whose specialty is constitutional and administrative law. The questions were: ‘How do we distinguish “Western values” from “Chinese values”?’; ‘How do we distinguish “attacking and slandering the Party’s leadership and blackening socialism” from “reflecting on the bends in the road in the Party’s past and exposing dark facts”?’ and ‘How should the Education Ministry that you lead implement the policy of governing the country according to the Constitution and the law?’

Pro-government commentators attacked Shen for posing what they characterised as misleading rhetorical questions. On the Communist Youth League website, two articles described Shen’s post as, respectively, ‘harbouring evil intent’ and ‘a dastardly deception’. Both referred to Shen’s post using the same stylised four-character phrase, ‘Shen Kui’s Three Questions’ 沈岿三问. Four-character phrases abound in Chinese as concepts, literary allusions, proverbs, and slogans. Official speeches make ample use of them, for their association with venerable traditions suggests that what they are saying is self evident or true. Besides, they are easy to memorise. ‘Absolute prohibition’ and ‘The Three Bottom Lines’ are examples of four-character phrases that the minister employed in the speech to which Shen was responding, as is ‘The Four Absolute Nos’, which online commentators used to describe Yuan’s speech.

Zhu Jidong 朱继东, Deputy Director and Party Secretary of the State Cultural Security and Ideology Building Research Centre 国家文化安全与意识形态建设研究中心 of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, went even further. Accusing Shen of distorting Yuan’s remarks to generate ‘ideological chaos’ 思想混乱, he called on ‘the relevant government agencies’ to investigate, prosecute and severely punish both Shen and others like him.

The controversy continued for a month or so. But media outlets were warned not to publish any more criticisms of Yuan’s speech. Consequently, on the Internet in the Mainland, denunciations of Shen, mostly appearing on state-sponsored websites, greatly outnumbered reports of Shen’s post and other commentaries critical of Yuan. The result was a carefully managed ‘struggle for public opinion’ 舆论斗争 (yet another four-character expression), as the state defended the unpopular directive and instructed its citizens precisely how it ought to be understood.

As noted in the 2014 Yearbook, the government under Deng Xiaoping introduced the phrase ‘the struggle for public opinion’ (one source dates its first appearance to a People’s Daily editorial in 1980), launching a full-scale propaganda campaign against ‘Western spiritual pollution’ in 1983. Then, ‘Western spiritual pollution’ was presented as an external threat. By 2013, the government had begun to perceive the threat as coming from within. For commentators in and outside China, the renaming of the ‘Seven Speak-Nots’ to ‘Western values’ in 2015 did not so much signal an ethnocentric, even xenophobic, attitude towards education so much as a crackdown on ‘liberalism’ in general.

The attack on ‘Western values’ is not a negation of the entire spectrum of ideas that have originated in Western countries. Academics in favour of one-party rule vigorously promote anti-liberal Western thinkers such as Carl Schmitt and Leo Strauss, for example. Above all, the Party-state seeks to bolster its particular interpretation of Marxism as a kind of inoculation against what is alternatively called, in the foreign-image-conscious, English-language Global Times, ‘suspicious values’.

On 5 May 2015, one day after Youth Day, the Party Secretary of Peking University laid the foundation stone for a new building on campus to be named after Karl Marx. The building is one of the university’s ‘Six Marx Projects’ 六马工程. First announced at a national forum on Marxism in higher education held at Peking University on 30 March, the six projects include the establishment of a new research centre on ‘The Chinese Path and Sinicised Marxism’; the compilation of ‘The Treasures of Marx’ 马藏, envisaged as the world’s most comprehensive collection of writings by Marx and studies of Marxism in Chinese and other languages; the founding of a centre housing materials on international Marxism; the hosting of the first-ever World Congress on Marxism (which took place on 10–11 October, with over 400 invited participants from more than twenty countries); the establishment of a website devoted to Marxism, and, of course, the construction of the Marx Building. The Baoshan Bank reportedly donated 100 million yuan towards the building. Yuan called in his speech for ‘the main teaching materials produced by the Marx Projects to be the key index for evaluating all teaching’.

The intensification of state-led initiatives to strengthen Marxism reflects the authorities’ growing fear that exposure to liberal ideas will encourage citizens to demand greater freedoms and to exercise their constitutional rights in ways that undermine the one-party system. Yuan was not proposing an outright ban on the study of such ideas, which can range from the kind of rights-based liberalism of the American philosophers Ronald Dworkin and John Rawls to the left-leaning defence of the public sphere mounted by the German social theorist Jurgen Habermas and his followers. Yuan wants people to conclude for themselves that Western liberalism is unsuitable for China. Yet the Party has its work cut out. Yuan and other leaders are aware that the internationalisation of the curriculum at Chinese universities, opportunities to study and travel abroad (opportunities eagerly taken up by many of their own children), as well as access to TED talks and MOOCs are just some of the many ways by which Chinese citizens can acquire knowledge about the full range of ‘Western values’.

The current assault on ‘Western values’ is only the latest of the campaigns against Western ideas since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. Like previous ideological drives, the 2015 campaign is conceived of as a form of intellectual hygiene. ‘Western values’ transmit ‘unhealthy feelings’. Only if everyone adheres to ‘The Four Absolute Nos’ and ‘The Three Bottom Lines’, can the country ‘secure a clean and upright atmosphere in our classrooms and lecture theatres’.

Socialist Hygiene

At the height of Russia’s civil war in 1919, there was a typhus epidemic. Lenin warned, ‘Either the lice will defeat socialism, or socialism will defeat the lice’. The remark has become a locus classicus for socialist hygiene. Disease and filth must be purged not only from physical bodies and environments but hearts and minds as well.

In her 1987 novel, Bathing 洗澡 (the published English translation is titled Baptism), the eminent writer Yang Jiang 杨绛 explored how socialist hygiene changed China during the PRC’s first ‘thought reform’ campaign, the ‘Three Antis Campaign’ 三反运动 of 1951. It was anti-corruption, anti-waste, and anti-‘obstructionist bureaucratism’. The process of self-examination and ordeals of public ‘self-criticism’ and confession by which the accused (many of whom were university educated) were required to undergo ‘self-criticism’ to show they were no longer germ ridden was informally nicknamed ‘bathing’. The type of intellectual hygiene demanded by the Xi-led party-state today involves none of the physical and emotional rigours of Maoist ‘bathing’: compliance with official directives is all that the authorities can hope to expect. But such campaigns can increasingly appear anachronistic to a population growing better educated and more cosmopolitan all the time.

Their defenders can also appear more than a little desperate. One of Shen Kui’s critics stated that Shen’s questions were as pointless as asking ‘why the American President must oppose terrorism, or why the people of Great Britain must pledge allegiance to the Queen’. But to liken ‘Western values’ to ‘terrorism’ or monarchism to a national creed is poor logic, and unlikely to convince the unconvinced.

The Party is certainly aware of the gulf between itself and the people, amply illustrated by ceaseless online ridicule of official mottos and slogans (see the 2012 Yearbook, Chapter 2 ‘Discontent in Digital China’, pp.118–141). In launching its ‘Mass Line Education and Practice Campaign’ in June 2013, Xi’s government aimed to close the gap, or at least prevent it from widening. The ‘Opinion’ of 19 January 2015 recognises the importance of winning over China’s intelligentsia. A key goal it lists is to ‘realistically strengthen the Party’s direction of propaganda and ideological work in higher education’, noting that this was a task of ‘extreme importance and real urgency’. ‘Realistically’ is the operative word here.

The state handsomely funds research into the topic of ‘Socialism with Chinese characteristics’. Party theorists and pro-government academics and writers have produced a prodigious number of books and articles on the subject. But the Chinese public’s reception of such works extends, in the main, from indifference to ridicule. There’s no guarantee that the Marx Projects will fare any better.

A Cancelled Reception

When ‘good cop’ ideological persuasion strategies don’t work, the Party employs punitive ‘bad cop’ backup tactics like censorship, harassment, intimidation, and even arrest and detention. The nationwide crackdown on feminists, rights defence lawyers, and others in 2015 (see Chapter 2, ‘The Fog of Law’, pp.64–89) attracted international attention and condemnation.

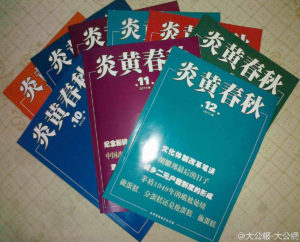

Less well known is the case of the influential monthly Yanhuang Chunqiu 炎黄春秋 (sometimes translated as China Through the Ages or The Chronicles of China). Founded in 1991 by veteran Communist Party members as a forum for independent intellectual inquiry, Yanhuang Chunqiu enjoys considerable authority in mainland intellectual and elite political circles. It is famous for publishing critical accounts of Party history written by retired senior officials with intimate first-hand knowledge of the events they discuss. Authors include Li Rui 李锐, former personal secretary to Mao Zedong, and Sun Zhen 孙振, former editor-in-chief at Xinhua’s Sichuan bureau, who worked under Premier Zhao Ziyang 赵紫阳, and who died under house arrest in 2005. Sun’s published defence of his former boss’s reputation infuriated Party leaders.

The seniority within the Party of many of Yanhuang Chunqiu’s editorial staff and contributors has made the magazine unusually resilient in the face of censorship. Even among the present-day Party leadership, few would wish to be remembered for publicly attacking elderly Communists who had played major roles in national and Party history. Despite occasional attempts to interfere with its masthead and organisation, and the temporary suspension of its website in January 2013 following the publication of an editorial in support of constitutionalism, the Party-state has never banned or closed down the publication.

Every year, for the twenty-three years of its existence, Yanhuang Chunqiu has held a fellowship reception around the time of Spring Festival celebrations. In addition to staff and regular contributors, the invitees typically include China’s leading liberal thinkers, advocates for political reform, and rights activists. The 2015 reception, with 240 invitees, was originally planned for 11 March. The magazine’s supervisory organisation, the Chinese National Academy of Arts, relayed instructions from unnamed authorities ‘有关部门’ for the event to be postponed to 18 March, until after the conclusion of the annual two-week meeting of the National People’s Congress (NPC). Whether under further orders or of its own volition, Yanhuang Chunqiu reduced its guest list to 130 as well. On 17 March, it was informed by the restaurant at the China Science and Technology Hall, where the reception was to have been held, that the event could not proceed after all. The organisers made a final appeal via the Chinese National Academy of Arts on 17 March but were refused. One invitee remarked that no one knew if the order had come from the Ministry of Culture, the Propaganda Department or the Public Security Bureau.

This was unprecedented. Throughout 2015, the government policed the magazine more strictly than ever before. Finally, on 1 July 2015, its editor-in-chief, Yang Jisheng 杨继绳, a former Xinhua journalist and the celebrated author of Tombstone 墓碑, about the Great Famine of 1958–1961, was forced to resign.

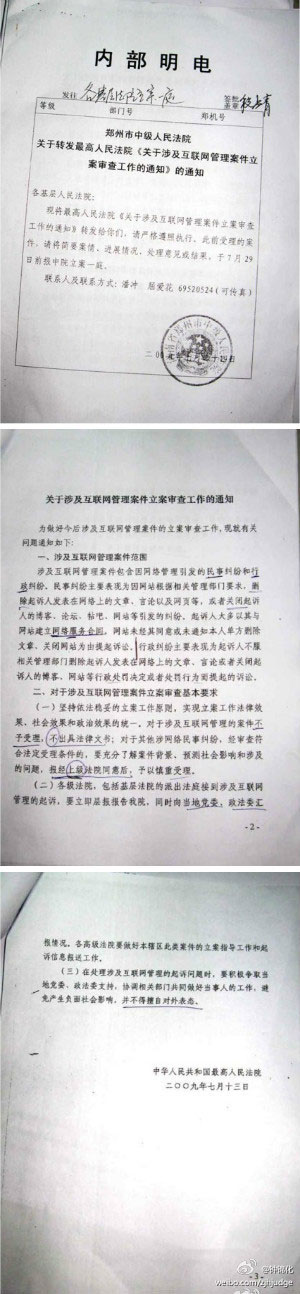

‘Three Notorious Factions’: the ‘Petroleum Faction’ in the blue circle, the ‘Secretary Faction’ in brown, and ‘Shanxi Faction’ in yellow

Image: zhiyin.cn

What’s in a Name?

Yanhuang Chunqiu had previously avoided trouble for two reasons. First, it never challenged the legitimacy of Communist Party rule. Second, the ideology of ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’, if sacred, has been open to relatively fluid interpretation since it was introduced in 1982. It is unlike in the Mao era, when phrases like ‘class struggle’ and the ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’ for example, were rigidly defined by Mao himself. ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’ initially described an attitude of cautious experimentation under one-party rule: ‘crossing the river by feeling the stones’ 摸着石头过河, to quote Deng Xiaoping quoting fellow Party elder Chen Yun 陈云. Since Xi assumed power in November 2012, however, the party-state’s tolerance for open discussion and debate on matters of public interest has shrunk and its appetite for ideological consolidation has grown.

In 2008, Yanhuang Chunqiu’s long-time publisher Du Daozheng 杜导正 described the magazine’s policy as ‘adhering to the big picture while opening up the small picture’ 大框框守住,小框框放开. The ‘big picture’ stands for the legitimacy of Party rule and ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’. The ‘small picture’ refers to the specific matters of public and historical interest explored by the magazine’s contributors. In 2011, Du advised that the Party needed to ‘do three things: implement intra-party democracy, undertake systemic reform of the National People’s Congress, and open up public opinion’. Du’s words carry weight: he joined the Party in 1937 and, in the 1980s was director of the General Administration of Press and Publications (GAPP), the state agency responsible for regulating public culture in that first decade of reform.

Party leaders and state media have used the term ‘intra-party democracy’ 党内民主 widely since the late 2000s. It refers to concepts such as competition and merit guiding official appointments, transparency in governance, and the sort of internal checks and balances that would mitigate against corruption and the abuse of power. ‘Intra-party democracy’ promotes collective leadership via negotiation and compromise among rival party factions. Those who openly promote ‘intra-party democracy’ are generally perceived—as is Yanhuang Chunqiu by most of the international media—as liberal leaning and on the Party’s ‘right’.

But political distinctions of ‘left’ and ‘right’ are often misleading in relation to the CCP. The ‘left’ usually describes people who defend Mao Zedong Thought and the Maoist legacy of central planning, and who seek to strengthen the power of the party-state and place high importance on propaganda and ideological work. Yet many on the ‘right’ also support these ideas. Similarly, if the ‘right’ refers to those who seek to advance China’s market economy and strengthen intra-party democracy, then all high-ranking Party leaders qualify as ‘right’. Like its predecessors, Xi Jinping’s government displays ‘left’ and ‘right’ tendencies at different times in relation to different issues.

In official discourse, ‘faction’ is a pejorative term. The Party is supposed to be a factionless organisation whose members are fully unified in their beliefs and values. Party factions are best understood, not in terms of ‘left’ and ‘right’ but as alliances based on personal networks formed around a central individual of influence and power. The US-based political scientist Cheng Li 李成 argues that elite politics in China revolves essentially around two of these ‘informal coalitions’. One is led by ‘princelings’. Also known as ‘Red Second Generation’, they are the descendants of historical CCP leaders and include Xi Jinping, son of Xi Zhongxun 习仲勋, as well as the now-disgraced and imprisoned former Party secretary of Chongqing, Bo Xilai 薄熙来, son of Bo Yibo 薄一波. The other coalition is that of the ‘populists’, sometimes referred to as ‘shopkeepers’: party members from humbler origins who worked their way up through the system, such as Hu Jintao 胡锦涛 and Zhou Yongkang 周永康, the latter to date the highest ranking official to be jailed for corruption.

An illustration of official use of the word ‘faction’ comes from a Xinhua article dated 4 January 2015. It named, for the first time, what it called ‘Three Notorious Factions’ 三大帮派 (the ‘Petroleum Faction’, the ‘Secretary Faction’, and the ‘Shanxi Faction’), as well as the disgraced officials associated with each of these. Xinhua’s explicit reference to ‘factions’, five months before the start of the trial of Zhou Yongkang, aimed to show how successfully Xi’s Anti-Corruption crusade had exposed and eradicated the rot from within.

The type of exposé for which Yanhuang Chunqiu is famous is altogether different. The magazine specialises in evidence-based narratives of events and persons that official accounts have distorted or suppressed. In 2014, the respected historian and public intellectual Zhang Lifan 章立凡described Yanhuang Chunqiu as allied with Xi’s faction. Xi’s late father, Xi Zhongxun 习仲勋, was one of the magazine’s early supporters. Yet in September 2014, the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT) ordered the magazine to affiliate with an agency under the Ministry of Culture, and demanded far stricter standards of acceptable content. In an interview with the South China Morning Post on 19 September 2014, Zhang suggested that the magazine ‘might have become a pawn in the power struggle between Xi and his political enemies, as the new affiliation order was made when Xi was on a tour of South Asia’.

In 2015, however, it became clear that Xi would offer the magazine no special protection. Following the cancellation of Yanhuang Chunqiu’s annual fellowship reception in March, on 10 April 2015, SAPPRFT notified the magazine that of the eighty-six articles published in the first four issues of 2015, thirty-seven violated state regulations. The offending articles addressed ‘topics of grave importance’ 重大选题 (the official term for censored or ‘sensitive’ topics) but had not been submitted to SAPPRFT for prior approval. The notice warned that further violations would not be tolerated.

On 3 June 2015, the People’s Liberation Army Daily posted an article on its Weibo account attacking Yanhuang Chunqiu for ‘spreading confusion and deceiving ordinary citizens, especially retired cadres’. Titled ‘Getting to the Bottom of Yanhuang Chunqiu’ 起底炎黄春秋, the article accused the magazine of ‘blackening Mao Zedong’s name, blackening the memory of the nation’s heroes and martyrs, and making history meaningless. In truth, it nullifies the history of New China and uses public opinion to try and drag China back to capitalism.’ The article was widely relayed on the Internet in the Mainland, attracting an overwhelming number of positive comments on state-sponsored websites, with only a minority defending the magazine. It was another well-orchestrated triumph in the party-state’s ‘struggle for public opinion’. On 25 December 2015, when Xi posted his very first Weibo message, he chose to do so on the People’s Liberation Army Daily’s Weibo account; the message was unremarkable (‘…realise the China Dream and the dream of a strong army!’ etc) but the media he chose to make it in was significant.

In two open letters written on 30 June 2015 and published online to mark his departure from Yanhuang Chunqiu on 1 July, Yang Jisheng confirmed that he had been forced to resign. He feared for the magazine’s future, noting that it had, from its inception, observed the ‘Eight Avoids’ 八不碰, carefully circumventing all references to ’June 4’, the separation of powers, Falun Gong, incumbent state leaders, the families of incumbent leaders, the transformation of the PLA from a Party to a state army, ethnic conflicts, and foreign relations. Yet this clearly was not enough. As of January 2016, a tightly constrained Yanhuang Chunqiu was still publishing.

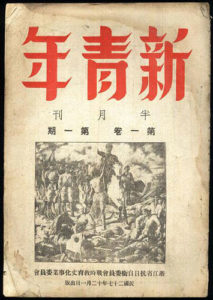

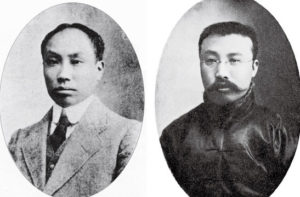

How to be a Good Communist

September 2015 marked the centenary of the founding of Youth magazine (renamed New Youth in 1917), two of whose founding members, Chen Duxiu 陈独秀 and Li Dazhao 李大钊, were also founders of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. New Youth and the New Culture Movement it initiated are widely perceived in mainland intellectual circles as the prologue to the founding of the CCP. At a forum convened in August 2015 to commemorate this centenary, the eminent historian Lei Yi 雷颐 mused that while the New Culture Movement (also known as the May Fourth Movement) is typically described as the starting-point of a fundamental rejection of traditional ideas, it was much less radical than its predecessor, the movement for constitutional monarchy led by Kang Youwei 康有为 and Liang Qichao 梁启超 during the last two decades of the Qing dynasty, from about 1890–1911. Lei argued that the final decades of the Qing represented a unique period in which Chinese intellectuals, including those in exile, began to discard the moral and political principles underpinning a disintegrating dynastic system. No longer in awe of the so-called ‘sacred decrees’ 圣旨 as a result of the Qing’s apparent inability to meet the challenges of the modern world, they were emboldened to challenge its authority.

Within ten years of the fall of the Qing, by 1921, the Nationalist Party (KMT) and the CCP had become China’s two dominant political organisations. Both were Leninist in structure and sought to achieve one-party rule in China. They were allies until 1927 and enemies thereafter. Lei described how in the Republican era, there was immense pressure on intellectuals to choose a side—CCP or KMT—even if they disagreed with both. The result was ‘an inner contradiction and an inner tension. Intellectuals were concerned about politics but lacked the power to produce political change. The parlous state of their society made it impossible for them to keep quiet. They felt compelled to do something but they also worried about their own professional careers.’ Worrying was justified, as neither party was kind to dissidents.

Among the examples provided by Lei was the case of Zhang Shenfu 张申府 (1893–1986). Zhang played a key role in the early dissemination of Marxism in China. He and Li Dazhao 李大钊 co-founded the Communist Small Group 共产党小组 at Peking University in 1920 and it was Zhang who recommended Zhou Enlai 周恩来 (China’s Premier from 1949 to 1976 and Deng Xiaoping’s mentor) for Communist Party membership. Lei noted that although Zhang fiercely advocated party discipline, he ultimately found it impossible to relinquish his intellectual independence and resigned from the CCP by 1925. After the Communist victory in 1949, Zhang obtained a position at the National Library in Beijing with Zhou Enlai’s help. Despite attempting to stay out of trouble, he was punished in 1957 as a ‘rightist’. Lei stated that Zhang embodied ‘the intellectual’s spirit of pursuing truth for its own sake’ and that he ‘never learned how to be agreeable’. Zhang was not politically rehabilitated until three years after Mao’s death, in 1979.

Lei and others who spoke at the commemorative forum made no mention of their own situation. Nothing was said of ‘The Four Absolute Nos’, the intensification of ideological instruction on university campuses or the plight of Yanhuang Chunqiu. However, the contemporary relevance of Lei’s remarks was not lost on forum participants. Historical innuendo is a well-established critical art in China.

Under Xi, party propagandists have produced numerous slogans describing the qualities the Party requires of its officials. One widely used four-character slogan in 2015 was the ‘Three Stricts and Three Genuines’ 三严三实: be strict with oneself in ‘moral cultivation, the use of power, and in the exercise of self-discipline’, while ‘planning and working in genuine ways and genuinely striving to be a decent person’. First used by Xi Jinping in a speech of 17 March 2014, official websites heavily promoted the slogan in June 2015. It was also the focus of the speech Xi delivered on 29 December 2015 at the ‘Democratic Life Meeting’ of the twenty-five-member Politburo. Xi told his colleagues to uphold the highest standards of ethical conduct and ‘strictly educate, manage and supervise’ erring family members and colleagues, to ensure their wrongdoings are ‘resolutely corrected’.

Another slogan, ‘It is unacceptable to be a nice guy’ 好人主义要不得, appeared in many articles published on official websites in 2015. Lei Yi had suggested that Zhang Shenfu’s inability ‘to be agreeable’ was a mark of his personal integrity. But the party’s idea of ‘not being a nice guy’ has nothing to do with speaking truth to power. It warns officials against abusing their power by ‘being nice’ to greedy relatives and friends.

In his famous 1939 tract ‘On the Self-Cultivation of Communists’, written when he was a leader of the Communist underground. Liu Shaoqi 刘少奇 urged his fellow Party-members to be fearless, selfless, and willing to die for the Communist cause:

As we Communists see it, nothing can be more worthless or indefensible than to sacrifice oneself in the interests of an individual or a small minority. But it is the worthiest and most just thing in the world to sacrifice oneself for the Party, for the proletariat, for the emancipation of the nation and all mankind, for social progress and for the highest interests of the overwhelming majority of the people.

Several articles published on official websites in 2015 described Xi’s ‘Three Stricts and Three Genuines’ as an exemplary emulation of the ideals presented in Liu’s 1939 tract. Yet none mentioned what Liu considered ‘worthiest and most just’. Words like ‘sacrifice’, ‘the proletariat’, and ‘the emancipation of all mankind’ have rarely appeared in official discourse since the 1990s. The goals of today are more vague, wordier, more practical, and more narrowly nationalistic: ‘to establish a well-off society and to fully realise the China Dream of reviving the greatness of the Chinese nation’ 建成小康社会,最终实现中华民族伟大复兴的中国梦. Launching his ‘Mass Line Education and Practice Campaign’ in June 2013, Xi spoke about self cultivation in a distinctly banal register. He asked Party members to ‘look in the mirror, make themselves presentable, take a bath and cure what ails them’ 照镜子、正衣冠、洗洗澡、治治病. In education and public culture, the Party-state under Xi’s leadership has used the rhetoric of ‘socialist hygiene’ to justify its intensification of censorship. Yet, Xi’s somewhat jocund remark reflects the predicament of a government whose legitimacy rests on its Communist past but for whom the very idea of being a good Communist has lost all meaning.

Notes — Intellectual Hygiene

‘Yuan Guiren: University teachers must defend the Three Bottom Lines of politics, law and ethics’ 袁贵仁:高校教师必须守好政治、法律、道德三条底线, Xinhuanet.com, 29 January 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/2015-01/29/c_1114183715.htm. Xinhua published a different perspective on Yuan’s speech in English the following day: ‘Education minister warns against “Western values” in colleges’, English.news.cn, 30 January 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2015-01/30/c_133958419.htm

Xinhua, ‘Yuan Guiren: University teachers must defend the Three Bottom Lines of politics, law and ethics’ 袁贵仁:高校教师必须守好政治、法律、道德三条底线, Xinhuanet.com, 29 January 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/2015-01/29/c_1114183715.htm

General Office and the State Council of the Chinese Communist Party中共中央办公厅、国务院办公厅, ‘An Opinion on Strengthening and Improving Propaganda and Ideological Work in Higher Education Under the New Circumstances’ 关于进一步加强和改进新形势下高校宣传思想工作的意见, Xinhuanet, 19 January 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/2015-01/19/c_1114051345.htm. An independent English translation of this document appears at the China Copyright and Media website, published 16 February 2015, online at: https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2015/01/19/opinions-concerning-further-strengthening-and-improving-propaganda-and-ideology-work-in-higher-education-under-new-circumstances/

CCP Central Organisation Department, CCP Central Publicity Department, CCP Committee of the Ministry of Education中共中央组织部 中共中央宣传部 中共教育部党组, ‘Sixteen Suggestions of the Chinese Communist Party on Strengthening Ideological and Political Work among Young Teachers in Higher Education’ 中共16条意见加强高校青年教师思想政治工作, People.cn, 28 May 2013, online at: http://edu.people.com.cn/n/2013/0528/c1053-21643996.html

Besides a wide range of expert commentaries, the controversy surrounding Yuan’s speech also attracted responses from Chinese students overseas. An article by Grace Zhang exemplifies the depth and scope of background information about Yuan’s speech that interested readers were able to access online. ‘教育部部长袁贵仁反对西方价值观念进入课堂背后的思想考虑’, The Journal of Political Risk, 10 July 2015, online at: http://www.jpolrisk.com/what-the-chinese-education-minister-is-really-trying-to-say/

Shen Kui’s post circulated under the title ‘Shen Kui poses three questions to Yuan Guiren’ 沈岿:三问袁贵仁. The translation here is by Donald Clarke, ‘Shen Kui and his three questions’, China Law Prof Blog, 31 January 2015, online at: http://lawprofessors.typepad.com/china_law_prof_blog/2015/01/shen-kui-and-his-three-questions.html

Translated excerpts appear in ‘China’s Search Engines Censor Searches for Scholar Who Questioned Education Minister’s Anti-Western Values Stance’, Fei Chang Dao, 16 February 2015, online at: http://blog.feichangdao.com/2015/02/chinas-search-engines-censor-searches.html

A commentary published on the national broadcaster CCTV’s website claimed that many of the commentators who referred to Yuan’s speech as ‘the Four Absolute No’s’ distorted the minister’s words, by wilfully misrepresenting his injunction against ‘the wrong Western values’ to portray him as a xenophobe who rejected all Western values. Dugu jiuduan 独孤九段, ‘Absolutely prohibit the use of materials on Western values in the classroom’? This was not what Yuan Guiren said,’ ‘决不让西方价值观教材进课堂’?袁贵仁原话不是这么说的, CCTV.com, 6 February 2015, online at: http://m.news.cntv.cn/2015/02/06/ARTI1423199157987218.shtml

‘CASS Institute Official: Punish Those Who Questioned Education Minister’, Fei Chang Dao, 17 February 2015, online at: http://blog.feichangdao.com/2015/02/cass-institute-official-punish-those.html

Screenshots taken on 2 February 2015 published on the Fei Chang Dao blog showed that searches for ‘Shen Kui’ and ‘Yuan Guiren’ had been blocked. However, either name returned results when it was searched separately. ‘China’s Search Engines Censor Searches for Scholar Who Questioned Education Minister’s Anti-Western Values Stance,’ Fei Chang Dao, 16 February 2015, online at: http://blog.feichangdao.com/2015/02/chinas-search-engines-censor-searches.html

Qian Gang, ‘Parsing the Public Opinion Struggle’, China Media Project, 24 September 2013, online at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2013/09/24/34085/

Minxin Pei, ‘China’s War on Western Values’, Project Syndicate, 10 February 2015, online at: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-censorship-economic-prospects-by-minxin-pei-2015-02; Hu Shaojiang, ‘Re-ideologizing Chinese Universities’, translated by Diana Zhang, China Change, 10 February 2015, online at: http://chinachange.org/2015/02/10/re-ideologizing-chinese-universities/; Siwen 思闻, ‘Culture Minister Yuan Guiren’s “Four Absolute No’s” are applicable to him’, 教育部长袁贵仁的四个绝不,对他也适用, kdnet.net, 9 March 2015, online at: http://club.kdnet.net/dispbbs.asp?boardid=44&id=10756037

See Flora Sapio, ‘Carl Schmitt in China’, China Story, 7 October 2015, online at: https://www.thechinastory.org/2015/10/carl-schmitt-in-china/

Zhou Yu, ‘Chinese university revives research on official ideology to head off suspicious values’, Global Times, 1 June 2015, online at: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/924726.shtml

‘The fourth national forum of Marxist institute directors within higher education opens at Peking University’, 第四届全国高校马克思主义学院院长论坛在北京大学召开, People.cn, 2 April 2015, online at: http://theory.people.com.cn/n/2015/0402/c40531-26791082.html; Zhou Yu, ‘Chinese university revives research on official ideology to head off suspicious values’, Global Times, 1 June 2015, online at: http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/924726.shtml; ‘Twenty-first century Peking University is once again a pinnacle of Marxist studies’ 北京大学21世纪再度成为研究马克思主义的高地, Xinhuanet, 11 October 2015, online at: http://edu.people.com.cn/n/2015/1012/c1053-27685253.html; Didi Kirsten Tatlow, ‘China Seeks to Promote the ‘Right’ Western Philosophy: Marxism’, The New York Times, 23 September 2015, reposted at https://u.osu.edu/mclc/2015/09/24/china-promotes-marxism/

BBC (Mandarin Chinese edition), ‘Controversy ensues over Yuan Guiren’s former remark that he did not fear Western materials entering China,’ 袁贵仁被揭曾称不怕引进外国资源引热议, BBC, 31 January 2015, online at: http://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/simp/china/2015/01/150131_china_education_yuanguiren

‘The Minister of Education calls on universities to defend the political baseline and ensure a clean and upright atmosphere in classrooms’ 教育部长:高校要守好政治底线 确保课堂风清气正, People.cn, 29 January 2015, online at: http://edu.people.com.cn/n/2015/0129/c1053-26475290.html

As translated in Tricia Starks, Body Soviet: Propaganda, Hygiene, and the Revolutionary State, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009, p.3.

Ministry of Culture notice, 10 August 2015, online at: http://www.mcprc.gov.cn/whzx/whyw/201508/t20150810_457407.html

‘China bans immoral songs online’, English.news.cn, 10 August 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-08/10/c_134501210.htm

‘China widens ban on immoral songs, supervision tightened’, English.news.cn, 12 August 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-08/12/c_134508535.htm

‘Stars respond to the removal of 120 vulgar online songs—DJ Luo Baiji: Getting banned is also good’ “众星回应120首低俗网络歌曲被下架 罗百吉:被禁也好”, News.youth.cn, 11 August 2015, online at: http://news.youth.cn/yl/201508/t20150811_6987198.htm

View online comments about the banned songs: https://twitter.com/majunlive/status/630936099485954048

Japanese anime ban: ‘Ministry of Culture announces first batch of Japanese anime to be put on ‘the black list’—38 films added to the blacklist’ “文化部公布首批网络动漫”黑名单” 38部产品上黑榜”, People.cn, 8 June 2015, online at: http://culture.people.com.cn/n/2015/0608/c172318-27121659.html; ‘Ministry of Culture formally announces illegal animation list: 38 animations are under investigation’ “文化部正式公布违规动画名单 查处38部动画”, Tencent, 9 June 2015, online at: http://comic.qq.com/a/20150609/017507.htm

‘Spotlight Back on Xi’s “Positive Energy” in Arts’, China Digital Times, 15 October 2015, online at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2015/10/spotlight-back-on-xis-positive-energy-in-arts/; Patrick Boehler and Vanessa Piao, ‘Xi Jinping’s Speech on the Arts Is Released, One Year Later’, The New York Times, 15 October 2015, online at: http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/10/15/xi-jinping-speech-arts-culture/?_r=0

‘Xinhua Insight: China’s Xi points way for arts’, Xinhuanet.com, 16 October 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-10/16/c_133719778.htm

Echo Zhao, ‘The 3 Generals of Chinese Sci Fi’, The World of Chinese, 30 December 2012, online at: http://www.theworldofchinese.com/2012/12/the-3-generals-of-chinese-sci-fi/

Judith Amory, ‘Translator’s Introduction’, Baptism, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2007, pp.ix-x.

‘Sci-fi writers urged to play a part in national revival’, Xinhuanet, 14 September 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-09/14/c_134623397.htm

Chen Qiufan, trans. Carmen Yiling Yan and Ken Liu, ‘The Smog Society’, Lightspeed, August 5, 2015, online at: http://www.lightspeedmagazine.com/fiction/the-smog-society/; Ma Boyong, trans. Ken Liu, ‘City of Silence’, World SF Blog, November-December 2011.

See for example, Renditions, no. 77/78 (Spring and Autumn of 2012), guest edited by Mingwei Song.

The document appears in English translation here: https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2015/01/19/opinions-concerning-further-strengthening-and-improving-propaganda-and-ideology-work-in-higher-education-under-new-circumstances/

The magazine’s title consists of two terms associated with China’s civilizational origins, Yan and Huang being the names of China’s mythological founders, and Spring and Autumn being the period of political turbulence in which Confucius lived. As C. A. Yeung puts it, the title is ‘an allusion to the great Confucian tradition of invoking history, as a way of admonishing the Head of State against undesirable influences’ and thereby to use history ‘particularly the history of Party founders, to set a standard for governance.’ https://underthejacaranda.wordpress.com/2008/11/18/the-unrelenting-du-daocheng-refuses-to-retire/

The cover story for Yanhuang Chunqiu’s September 2008 issue was a personal essay by Sun Zhen titled ‘My relationship with the Sichuan Party Secretary in the late stages of the Cultural Revolution’. The magazine and Sun not only defied the official ban on discussions of Zhao’s legacy, it contradicted the official verdict of Zhao as a failed leader who ‘made significant errors when carrying out ideological and practical tasks.’ The magazine’s supervisory body, the Ministry of Culture, demanded Du Daozheng’s resignation as editor-in-chief. Du refused initially but relinquished the editorial role in February 2009 to continue solely as the magazine’s registered proprietor. http://cmp.hku.hk/2008/11/22/1378/; http://www.thechinabeat.org/?p=297

Qiao Long, ‘Radio Free Asia exclusive: Forced cancellation of Yanhuang chunqiu reception: Hu Qili, Tian Jiyun and other former senior Party officials will not be able to attend’, RFA独家:炎黄春秋新春联谊会被迫取消 胡启立田纪云等前中共高层无法出席, Radio Free Asia, 17 March 2015, online at: http://www.rfa.org/mandarin/yataibaodao/meiti/ql3-03172015100248.html. See also http://minzhuzhongguo.org/ArtShow.aspx?AID=51644; http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1742290/chinese-political-magazine-yanhuang-chunqiu-forced-call-annual-dinner

An unnamed source quoted in a Radio Free Asia report of 27 April 2015 stated that in April, retired officials from Xinhua News and the Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection visited Yang at his home to demand his resignation. They acceded to Yang’s request for the resignation to take effect from 1 July 2015. Qiao Long, ‘Chinese Magazine Warned by Censors, Future Now Uncertain’, Radio Free Asia, 27 April 2015, online at: http://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/warned-04272015103205.html

A translation of the interview with Du Daozheng appears in David Bandurski, ‘Du Daozheng on China’s past and future’, China Media Project, 8 November 2011, online at: http://cmp.hku.hk/2011/11/08/17050/

Cheng Li, ‘Intra-Party Democracy in China: Should We Take It Seriously?, Chinese Leadership Monitor, No.30 (2009), http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/papers/2009/11/fall-china-democracy-li/fall_china_democracy_li.pdf

Beijing Times, ‘The media names three Party factions: Jiang Jiemin et al are the “Petroleum Faction” ’ “媒体为党内三大帮派命名:蒋洁敏等是“石油帮”, Xinhua.net, 4 January 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-01/04/c_127355066.htm

Minni Chan, ‘Order to ‘realign’ outspoken liberal magazine will end its independence, says publisher’, South China Morning Post, 19 September 2014, online at: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1595608/order-realign-outspoken-liberal-magazine-will-end-its-independence-says

‘Two open letters to mark my departure as editor-in-chief of Yanhuang chunqiu’ 离开《炎黄春秋》总编岗位的两封公开信, Boxun.com, 16 July 2015, online at: http://www.boxun.com/news/gb/china/2015/07/201507160051.shtml#.Vsw4xvl96Uk

Xue Zhibai薛之白, ‘Army paper blasts Yanhuang chunqiu and makes waves’ “军报炮轰《炎黄春秋》掀波澜”, Zaobao.sg, 4 June 2015, http://www.zaobao.com.sg/special/zbo/commentary/story20150604-487879

The post read: ‘On the occasion of the coming new year, I extend my greetings to all the PLA commanders and fighters, armed police officers and militia reservists on behalf of the CPC Central Committee and the CMC. I hope that we will all endeavour to achieve the goal of enforcing the army and fulfilling the missions efficiently, making new greater contributions to realize the dream of China and the dream of a strong army!’, Sina English, 28 December 2015, online at: http://english.sina.com/china/2015/1227/876835.html

‘Dalai Lama concedes he may be the last’, BBC, 17 December 2014, online at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-30510018

Christopher Bodeen, ‘Atheistic China claims ‘right to reincarnate’ Dalai Lama, Salon, 13 May 2015, online at: http://www.salon.com/2015/03/13/atheistic_china_claims_right_to_reincarnate_dalai_lama/

Nicholas Kristof, ‘Dalai Lama Gets Mischievous’, New York Times, 16 July 2015, online at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/16/opinion/nicholas-kristof-dalai-lama-gets-mischievous.html?_r=0

‘Zhu Weiqun: Buddhist reincarnation is the decision of the state’, Global Times 环球时报, 30 November 2015, online at: http://opinion.huanqiu.com/1152/2015-11/8069191.html

Yang Jisheng, ‘Two open letters on the occasion of my departure as editor-in-chief of Yanhuang chunqiu离开《炎黄春秋》总编岗位的两封公开信, Boxun.com, 16 July 2015, online at: http://www.boxun.com/news/gb/china/2015/07/201507160051.shtml#.VtU-_Pl96Uk

Lei Yi, ‘The hundred-year solitude of Chinese intellectuals’ 中国知识分子的百年孤寂, lecture transcript, Veritas, 10 August 2015, online at: http://dxw.ifeng.com/shilu/jiangtangshilu237/1.shtml

On Zhang Shenfu’s life, see Vera Schwarcz, Time for Telling Truth is Running Out: Conversations with Zhang Shenfu, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992

Lei Yi, ‘The hundred-year solitude of Chinese intellectuals’, http://dxw.ifeng.com/shilu/jiangtangshilu237/1.shtml

Xi Jinping discusses “Three Stricts and Three Genuines” – a compilation of important statements since the Eighteenth Party Congress’ “习近平论“三严三实”——十八大以来重要论述摘编”, first published in Party Building 党建, 4 June 2015, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-06/04/c_127878723.htm

People’s Daily, ‘Political Bureau of the CCP Central Committee holds its Democratic Life Meeting; Party General Secretary Xi Jinping presides and delivers a key speech’ “中共中央政治局召开专题民主生活会 中共中央总书记习近平主持会议并发表重要讲话”, www.cpc.new.cn, 30 December 2015, online at: http://dangjian.people.com.cn/n1/2015/1230/c117092-27993347.html

The expression first appeared as the title of an article by Yu Yongjun, published on the People’s Daily website on 25 October 2013 (人民日报纵横:好人主义要不得 http://opinion.people.com.cn/n/2013/1025/c1003-23320405.html)

Liu Shaoqi, ‘How to be a good Communist’, first published in Chinese July 1989, English translation in Selected Works of Liu Shaoqi, Volume One (Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1984), available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/liu-shaoqi/1939/how-to-be/ch06.htm

Wen Yan文岩, ‘Raising the standard of Communist self-cultivation is a perennial lesson in Party construction — revisiting Liu Shaoqi’s How to be a good Communist’ “提高党员修养是党的建设的永久性课题——重温刘少奇《论共产党员的修养》”, 9 July 2015, People.cn, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n/2015/0709/c1001-27275286.html

The removal in February 2008 of ‘revolutionary’ from the title ‘revolutionary martyr’, posthumously awarded to individuals who died in service to the nation, marked a key moment in the erosion of pre-1949 and Maoist Communist rhetoric. See Jane Macartney, ‘The Revolution is Dead’, The Times, 22 February 2008, online at: http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/asia/article3412469.ece

Su Chaoli 苏超莉, ‘Realising the “Three Stricts and Three Genuines” strengthens the cultivation of Party spirit’ “践行“三严三实” 加强党性修养”, cpcnews.cn, 21 October 2015, online at: http://dangjian.people.com.cn/n/2015/1021/c117092-27722862.html

Xinhua, ‘Xi Jinping delivers a key speech at the opening of the conference on Mass Line Education and Practice Campaign’ “党的群众路线教育实践活动工作会议召开 习近平发表重要讲话”, 18 June 2013, online at: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2013/0618/c64094-21884638.html

‘Taking stock: Xi Jinping’s 20 new catchwords of 2015’ “盘点:2015年习近平的20个‘新热词’ ”, People’s Daily 人民日报, 28 December 2015, online at: http://politics.people.com.cn/n1/2015/1228/c1001-27984291.html

Paul Burgman Jr., Andrew M. Friedle, ‘China’s Political Culture is Paralyzing its Economy’, The National Interest, 2 May 2016, online at: http://nationalinterest.org/feature/chinas-political-culture-paralyzing-its-economy-16019

‘Since the 18th Party Congress, Xi Jinping has mentioned “new normal” over 160 times’ 18大以来,习近平提及“新常态”160余次, People’s Daily 人民日报, 12 March 2015, online at: http://news.ifeng.com/a/20160312/47804216_0.shtml

Zheping Huang, ‘China’s Communist Party has banned its members from meeting alone or criticizing the Party’, Quartz, 28 October 2015, online at: http://qz.com/530534/chinas-communist-party-has-banned-its-members-from-meeting-alone-or-criticizing-the-party/