Towards the end of 2014, Xi Jinping addressed a meeting of ‘arts and culture workers’ 文艺工作者座谈会 for two hours. Moving beyond his prepared script, he spoke glowingly of the influence of art and literature on himself as a youth and argued that culture is crucial to the realisation of the China Dream. Not just any culture, however: Xi evoked both the ancient notion of ‘culture with moral purpose’ 文以载道 as well as the Soviet concept of artists as the ‘engineers of human souls’. Xi also noted the importance of culture to Chinese soft power, stating that ‘historically, the position and influence of the Chinese people’ in the world was due not to military might but the strong appeal of Chinese culture.

Uniqlo in Beijing’s Sanlitun Shopping Village, where a couple filmed themselves having sex in one of its changing rooms

Photo: gawker.com

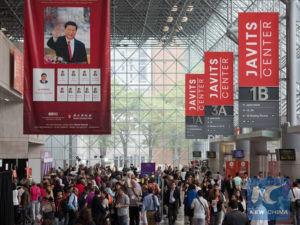

Chinese cultural soft power received an unexpected boost when Liu Cixin 刘慈欣, the author of The Three Body Problem, became not only the first Chinese but first Asian writer to win the international Hugo Award for best science fiction or fantasy in 2015. Official soft power strategy that relies on a spreading network of Confucius Institutes around the world has done less well: in late 2014 and into 2015, a number of prestigious tertiary institutions including the University of Chicago and Stockholm University have either shut down or refused to host Confucius Institutes, citing their incompatibility with the principles of free intellectual inquiry. And while the Chinese publishing industry’s 500-strong delegation may have been the special guests of the publishing trade fair BookExpo America in June 2015, US media were more interested in an anti-censorship rally organised to coincide with the book fair and attended by the Chinese writer Murong Xuecun 慕容 雪村 along with Jonathan Franzen and other notable American writers. The demonstration, organised by the PEN American Center, called for the release of Chinese writers including Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波 and the Tibetan poet Tsering Woeser from prison and house arrest. Protesters held up a sign: ‘Governments make bad editors’.

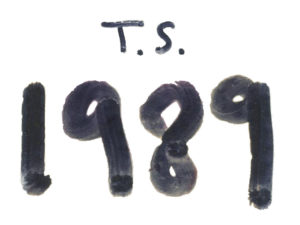

Taylor Swift’s clothing line ‘TS 1989’—an unintentional reference to the Tiananmen Square protests

Source: commons.wikimedia.org

That may be so, but the Chinese government shows no sign of putting down its red pen. If anything, censorship of media and literature intensified in 2015. The Party-state has long justified censorship with the use of environmental metaphors—the elimination of filth and pollution—as in 1983’s ‘anti-Spiritual Pollution’ campaign. In April 2015, it launched its latest ‘anti-porn’ campaign. (Only three months later, a couple uploaded a video of themselves having sex in a changing room in a branch of popular clothing chain Uniqlo in Beijing’s Sanlitun Shopping Village: by the following day, some 2.5 million searches and posts made the amateur porn video the top-trending item on WeChat.) In June, the censors proscribed thirty-eight Japanese anime including titles such as High School of the Dead and Psycho Pass as well as others with anti-authoritarian themes. The following month, the authorities cancelled a Shanghai concert by the American band Maroon 5, reportedly because one of the band members had tweeted a happy birthday message to the Dalai Lama. In August, the Ministry of Culture banned 120 songs from the Internet on grounds of promoting obscenity, violence, crime or harm to social morality, including Taiwan pop singer Chang Csun Yuk’s 张震岳 comedic ‘Fart’. In September, it axed Bon Jovi’s September tour to Beijing and Shanghai—five years earlier, Bon Jovi had displayed the Dalai Lama’s picture while playing in Taiwan. Taylor Swift, scheduled to visit China as part of a global tour in November, gave the authorities a fresh headache when several months beforehand, she revealed her latest ‘merch’, t-shirts, hoodies, and more, displaying her initials and the year of her birth—T.S. 1989, unintentionally evoking the events of Tiananmen Square twenty-six years ago. The Minister for Education Yuan Guiren 袁贵仁, meanwhile, was busy fighting pollution on another front, writing in early 2015 that universities should scrap texts that promoted ‘Western values’. (See Chapter 3 ‘Intellectual Hygiene—Mens Sana’, pp.100–127.)

Artists and writers who have run into difficulty exhibiting or publishing at home have long relied on outlets and markets outside China. In 2014, the authorities literally pulled the plug on the Eleventh Beijing Independent Film Festival by cutting off the electricity supply. In August 2015, Cinema on the Edge: Best of the Beijing Independent Film Festival 2012–2014 screened in New York City across a number of venues including the Asia Society.

Meanwhile, in June, Ai Weiwei 艾未未, China’s most famous artist-provocateur, was allowed to exhibit in China for the first time since his imprisonment for eighty-one days in 2011 and subsequent house arrest. In July, the authorities handed him back his passport. He travelled abroad, spoke about government control and repression in the mildest possible terms, attended a major show of his work at London’s Royal Academy of the Arts, and returned to China with-out incident before travelling again, including to Australia and Greece.

Notes

People’s Daily Wechat: outside the draft, what did Xi Jinping say at the literature and arts forum?’ “人民日报微信:通稿之外习近平在文艺座谈会上还讲了什么?”, cpc.news.cn, 16 October 2014, online at: http://cpc.people.com.cn/n/2014/1016/c64094-25848060.html

David Volodzko, ‘China’s Confucius Institutes and the Soft War’, The Diplomat, 8 July 2015, online at: http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/chinas-confucius-institutes-and-the-soft-war/