There is no corner of the Chinese Internet that is free of control. Buying broadband requires a government ID. Think you’ll use café WiFi? That now requires a phone number verification, which is linked to your ID. Or join a large group — one with more than 100 people — on WeChat 微信, China’s ubiquitous messaging app? You first have to register a bank account on WeChat to make doubly sure you are who you say you are. Want to post on an online forum? Don’t think you can hide behind your made-up username. They’ll want real name verification. And be careful — what you post, or even re-post, may have legal consequences.

Back in 2014, Lu Wei 鲁炜, until recently the head of the Cyber Administration of China 国家互联网信息办公室 (CAC), said, ‘The Internet is like a car. If it has no brakes … once it gets on the highway you can imagine what the end result will be. And so, no matter how advanced, all cars must have brakes.’ As China’s Internet gatekeeper, Lu was prone to metaphor about the need for order in cyberspace: in those same remarks, he described ‘freedom and order’ as ‘twin sisters’ that ‘must live together’. The Chinese Internet of 2016 has more than just brakes — it is subject to a regime of ever-stricter control and supervision. A Chinese individual in 2016 has a better chance of anonymity offline than online, away from the thousand prying eyes of China’s army of censors.

In the early days of the Internet, many people globally assumed that cyberspace would elude the state’s effort to control it. US President Bill Clinton famously quipped in 2000 that controlling the Internet would be like ‘nailing jello to a wall’. ‘Liberty will spread by cell phone and phone modem’, he proclaimed. ‘Imagine how much it could change China.’

Chinese officials imagined just this — and then took steps to stop it. In the mid-1990s, China’s Ministry of Public Security 公安部 (MPS) kicked off its ‘Golden Shield Project’ 金盾工程 — a far-ranging attempt to harness emerging information technologies for policing. Officials envisioned the integration of citizens’ official files into a nationwide registry and the inception of data-driven surveillance. Yet they were also aware that developments in informational technology could outpace the speed at which the Party could control it. As the number of Internet users skyrocketed (from 22 million in 2000 to 721 million by 2016), the MPS focused on the more immediate task of stemming the virtual flow of unfiltered information into the country. They set up a series of filters and blocks at Internet ‘choke points’ where fibre-optic cables entered the country. The Internet in the US and other places is designed specifically to be porous and lack ‘choke points’, but for China these access points served as digital borders that needed to be controlled. With the help of the American technology conglomerate Cisco, they installed mirroring routers — the same filtering technology used by companies or schools, just on a much larger scale — that reflect the pulsating light of incoming traffic into government servers, creating an effective digital veto by which the authorities could keep unwanted websites or keywords from entering the country.

Today, the ‘Great Firewall’ — a name given to China’s multifaceted system of Internet censorship by Geremie R. Barmé and Sang Ye in an article they wrote for Wired magazine in 1997 — is a sophisticated, finely tuned machine. The Great Firewall not only involves blocking external information, but also finding and proscribing politically-sensitive content generated from within China. It is not only capable of censoring content across the Chinese Internet, but also promotes a culture of self-censorship and control. International observers supposed that such control would stifle the ingenuity that led to the rise of IT hubs like Silicon Valley elsewhere in the world. Instead, China’s regime of online control has spurred its own form of domestic technological innovation and entrepreneurship, creating mini-Silicon Valleys across the country.

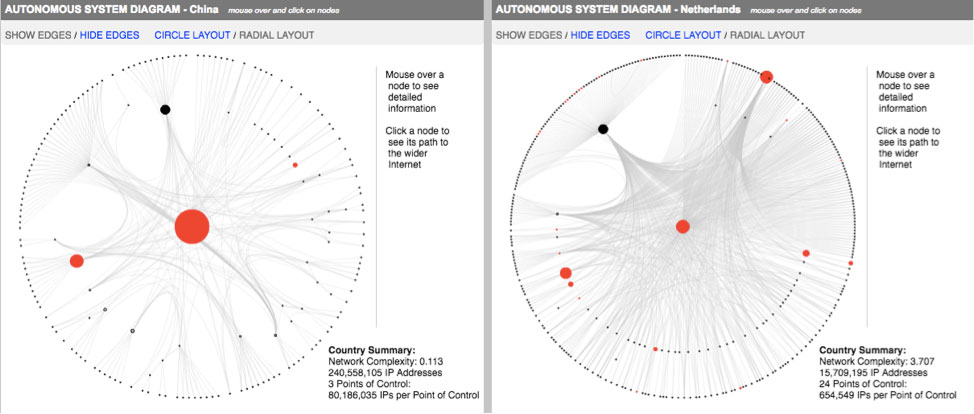

Mappings of comparative routes to the outside web shows the vast difference between China, where two IPs (Internet Protocol address) filter a majority of traffic, and the Netherlands, which has 24 points of control

Source: cyber.harvard.edu/netmaps/geo_map_home.php

Apple ‘appears’ to have made special accommodations in China by putting user data on government servers and installing a government-required WiFi protocol on phones, the US Justice Department have said

Photo: Baetho, Flickr

In April 2016, US trade officials formally accused China’s Great Firewall of being what the executives at foreign Internet companies have been calling it for years: a ‘trade barrier’. Chinese Internet regulators demand that companies surrender a much higher degree of control over software and user data than foreign companies can reasonably provide. Not only are China’s Internet regulations and censorship cumbersome and hard to navigate, but technology companies, including Apple, that have broken into the Chinese market risk endangering their position on user privacy globally. In February 2016, China made an unexpected appearance during a showdown between Apple and US law enforcement over the San Bernardino gunman’s encrypted iPhone, which Apple refused to unlock for investigators. During the court hearings, prosecutors cited Apple’s compliance with Chinese government requests to undercut Apple’s pro-user privacy position. Whether or not Apple secretly provided Chinese authorities with a backdoor to circumvent user encryption protection — as a Faustian bargain for access to the Chinese market — remains a lingering concern among privacy advocates.

By changing the rules of the Internet, the Chinese government has been able to nurture a trio of domestic Internet giants, commonly known as BAT (Baidu 百度, Alibaba 阿里巴巴集团, and Tencent 腾讯), which is willing to subscribe to the Party’s regime of control. Most censorship doesn’t occur at the internet service provider (ISP) level, but on individual platforms, which Chinese companies must police vigilantly. It’s no surprise that Chinese super-apps such as WeChat are built to facilitate censorship, creating a seductively convenient — and easily manageable and monitored — online space where the user can chat, bank, order taxis, send money to other users, pay bills, and even donate to charities. As Chinese apps and technology interweave with Chinese citizens’ everyday existence, so does Beijing’s control.

Freedom and Order: The Legacy of Lu Wei

On 29 June, without explanation or warning, the Chinese media reported that Lu Wei had stepped down from head of CAC, ending his three-year tenure as China’s all-powerful Internet gatekeeper. Although Lu’s brash, flamboyant style had made him enemies, his sudden deposition, unaccompanied by any sign of a clear political future, caught many observers by surprise. The media hailed his successor, Xu Lin 徐麟, who is close to Xi Jinping and previously served as Shanghai’s propaganda chief, as China’s biggest ‘political star’.

Whatever the reason for Lu’s dismissal — a half a year later, the cause of Lu’s fall remains unclear — his legacy is beyond question. While Internet freedom advocates celebrated the expansion of the free web, Lu launched a successful bid to bring China’s cyber environs under state control, proving that China could assert its ‘cyber sovereignty’ 网络主权. So far, Xu Lin has proven to be a reliable steward of Lu’s legacy, mobilising the expanding bureaucracy he created to police the Chinese web while keeping a lower profile than the attention-hungry Lu.

Early on, Lu showed an appreciation of the Internet that eluded most cadres in the Party. Writing in 2010, Lu argued in an article in Seeking Truth 求是 — the Party’s theory journal — that China would not have national security until it achieved ‘information security’ 信息安全. When Xi Jinping took power in 2013, the Internet was posing an ever-more complex and vexing challenge to CCP rule. Activists in the Middle East and elsewhere were using the Internet to help wage revolutions and people’s revolt. Meanwhile, China’s own forums and message boards were filling up with a unique class of independent voices: ‘self-media’ 自媒体, or what might be called public opinion ‘influencers’ which could hijack the public discourse from the stodgy propagandists with a single Weibo post — a prospect that the Chinese government found increasingly inconvenient. When a high-speed train in Wenzhou derailed in 2011 and the government attempted to cover up both the details of the tragedy and its cause (construction compromised by corruption), netizens poked holes in the official story faster than censors could erase their comments. They mocked and criticised the government, whipping up public anger into a frenzy that led to a series of official apologies, including an emphatic, personal apology from the president of the Shanghai Metro, Yu Guangyao 俞光耀, in the form of a bow during a televised press conference. In an article at the time, New Yorker journalist Evan Osnos quoted a Weibo user saying that the bow was a ‘sign of progress’.

Evidently, government officials were eager to avoid bowing too frequently, and Lu Wei was ready to help their cause. He was tasked with imposing government control over China’s raucous virtual public square, first as the chairman of the State Council Information Office 国务院新闻办公室 (SCIO), then as the head of the CAC. Lu showed that the same tools of fear and intimidation used by authoritarian states to police its citizens offline were equally effective online. As Xi Jinping said in a secret speech on propaganda and ideology work in 2013, which was later leaked to China Digital Times 中国数字时代, authorities would need to ‘unsheathe the sword’ 亮剑 to win the public opinion struggle online. Lu did just that, adding a little showmanship in the process.

After taking over the SCIO, Lu assembled the most influential online social icons (often known as the Big Vs for having verified accounts on Weibo) for dinner outings, where he warned them that speaking out against the Party would have repercussions. As if to prove his point, in August 2013, while Lu was hosting his star-studded soirées, Chinese authorities arrested Charles Xue 薛必群 — a Chinese American businessman and influential microblogger. While he was arrested for soliciting prostitution, no one doubted the real reason for his arrest. In a humiliating televised-forced confession, Xue stated that he had used his online influence irresponsibly to stroke his vanity, saying that fame online made him feel like an ‘the emperor of the Internet’. Other would-be Internet emperors took notice. A former employee of Weibo, who worked in the online platform’s censorship department in Tianjin between 2011 and 2013, told the Committee to Protect Journalists:

The effect was felt immediately. The amount of original posting dropped rapidly. Users not only withdrew from serious commentary, but became reluctant to post about what they heard or saw in their daily lives, because any information not confirmed by government authorities could potentially be deemed as creating or spreading rumours.

In 2014, Xi Jinping convened the first meeting of the Central Leading Group for Internet Security and Informatisation 中央网络安全和信息化领导小组, and established the CAC with a broad mandate for cyber control with Lu Wei at the helm. Under Lu, online censorship spiked. The CAC began requiring real-name verification for online activity and pushed for the criminalisation of the act of spreading of online ‘rumours’. (See the China Story Yearbook 2014: Shared Destiny, Chapter 3 ‘The Chinese Internet ‘Unshared Destiny‘).

April 2016: Xi Jinping presides over a symposium on cyberspace security and informatisation in Beijing

Source: news.cn

Lu also dispelled any doubt that China’s biggest Internet companies, which are privately owned, could be effective collaborators with the Party — even if following the Party’s tune occasionally required a little nudge. The CAC normalised the practice of summoning leading tech executives to the CAC office for reprimand. In 2015, in a rare public censure, the CAC even threatened to close down Sina 新浪 — China’s largest news portal — if the company did not tighten censorship of its online news service.

For the most part, however, officials have used the carrot rather than the stick to get Internet companies to work with the Party-state to achieve its vision for the Internet. The state leads the drive to increase popular access to the Internet, bringing millions of new Chinese users online each year — from the companies’ perspective, customers. It pays to be on the Party-state’s good side. (See Forum ‘Crayfish, Rabies, Yoghurt, and the Little Refuting-Rumours Assistant‘)

The caption above the image reads: ‘Today is so-called “April Fools’ Day” in the West. ‘April Fools’ Day does not accord with Chinese traditional values or socialism’s core value system. We hope everyone will not believe, start, or spread rumours J’

Image: Weibo

During Lu’s tenure, online content frequently disappeared without any apparent rhyme or reason. This is because the actual work of censorship in China is highly decentralised, managed between local CAC offices and individual platforms and sites (which are responsible for self-policing). Researchers at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab compiled a list of keywords blocked on China’s three major video streaming apps and found that they differed from platform to platform. There was one notable exception: each platform blocked the name of its competitors.

In December 2015, Lu Wei suggested that, like most people, he too had been inconvenienced by censorship, but that ‘online space and actual society are the same — we want freedom but also order’. It’s clear the CAC wants Chinese netizens to subscribe to the same logic and become active participants in the policing of their fellows. Websites and online platforms such as WeChat feature a prominent ‘report’ 报告 button. The website of the CAC itself seeks to educate and involve people in the censorship process by publishing rafts of statistics on censored content and sites that have been shut down. During one ‘clean up’ 净网 operation in 2016 alone, the CAC claimed to have shut down over one million accounts and closed more than 2,000 sites for disseminating ‘pornography, false rumours, and violent or other illegal content’. If you want to report content directly to the CAC yourself? The site provides an easy to remember phone number and URL (12377.cn). There’s even an app.

Spiritual Garden or Cultural Wasteland?

With its legions of censors and culture of self-censorship, the Chinese Internet has become, in Xi’s words, ‘clean and chipper’ 晴朗 — at least as far as direct threats to Party rule are concerned. But the CCP aspires to a higher plane of control, in which China’s Internet becomes nothing less than a ‘spiritual garden’ 精神家园 — an ennobling space where netizens complete their transformation into perfect citizens. With over 700 million users, the Internet is increasingly the Party’s most direct channel to its citizens, and it employs both online spectacle and its command over information to achieve this end.

In recent years, both Party publications and journals of theory have given expression to dreams of control and the potential of big data to enhance state control in the online sphere. The high-level policy document released in September outlining the government’s plan for a ‘Social Credit System’ 人信用监督 brought such dreams one step closer to reality. (See Forum ‘Cyber Loan Sharks, Social Credit, and New Frontiers of Digital Control’) In a speech to an audience of 1.5 million political and legal officials in October, Alibaba’s Jack Ma 马云 teased officials with what big data could accomplish — and implicitly what Alibaba could offer the government — by describing a Minority Report–style future in which big data could predict who will commit a crime, providing ‘a kind of predetermined sentencing’.

For the time being, the CCP is focused on what officials like to refer to as a ‘cleansing’ 清理 of the Internet to eliminate harmful elements. At a conference on cyber security and propaganda in 2015, Lu Wei said that the government must ‘consciously eliminate filth and mire such as online rumours, online violence, sex, and vulgarity’, and ‘foster online behavioural norms that venerate virtue and are inclined towards the good, use outstanding ideas, morals and culture to nourish the network and nourish society’.

In 2016, authorities took solid aim at the ‘filth and mire’. In April, The State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film, and Television 国家广播电影电视总局 (SAPPRFT) censured Jiang Yilei 姜逸磊, a celebrated comedian and online blogger known as ‘Papi Jiang’ (‘Papi’ 酱), for using vulgar language. A number of freewheeling videos were removed from her Youku 优酷 channel, though after vowing to ‘broadcast more positive energy’, she was allowed to continue posting videos. Other targets of the Party’s drive for web purity were less lucky. In 2016, authorities cracked down on China’s growing live-streaming sites, doling out strict new regulations and imposing harsh punishments on online users found violating the rules. One twenty-one-year-old ‘cam girl’, Xue Liqiang 雪梨枪 was sentenced in November to four years in prison for posting obscene videos.

SAPPRFT also imposed strict new guidelines and approval processes on the burgeoning online gaming scene. The leaked transcripts of one Chinese game company’s exchanges with the regulators revealed a frustrating and expansive list of official concerns, from bare-chested male characters, to ‘forbidden characters’ (like death 死 or rob 抢), and the excessive use of English-language words.

The Party’s ‘cleansing’ of the Internet does not appear to have left it on the cusp of ‘a golden age of Internet culture’ 联网文化的黄金时代, as state-media has declared, but rather with less culture. In the months after Papi Jiang’s censure, and her voluntary adoption of ‘positive energy’, the comedian’s star has faded. And despite the Party’s best attempts and claims to the contrary, the Chinese Internet today is far from a clean, moral space. It is rife with financial and other scams, salacious content, and rumours.

As for regular media portals, the CAC regularly censures news sites for lewd content, ‘clickbait’ headlines, and rumour peddling. In July, it issued a strict ban on media outlets from quoting unverified information sourced on social media. Yet without credible, independent media, rumours and disinformation spread like wildfire. The Party’s solution: more control.

Avoiding the ‘Digital Qing’

At the Cybersecurity and Informationalisation Work Conference 网络安全和信息化工作座谈 in April, President Xi began his most important speech of the year on Internet control with a journey through history. ‘There have been three major qualitative leaps in social development’, Xi said, ‘the agricultural revolution, the industrial revolution, and now the informational revolution. The China of the Qing dynasty was caught unprepared by the industrial revolution, resulting in one hundred years of national humiliation. China today must, by contrast, embrace the potential of the informational revolution to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.’

Chinese officials and the media often repeat that China is an ‘Internet big country’ 网络大国 on its way to becoming an ‘Internet superpower’网络强国. Most countries consider the Internet in terms of open borders and win-win cooperation. In contrast, China has applied the nation-state paradigm to the Internet, constructing digital borders and casting Internet development as a zero-sum arms race. On 7 November 2016, the National People’s Congress 全国人民代表大会 (NPC) gave this view legislative force with the new Cybersecurity Law 网络安全法, ignoring intense opposition from international tech companies. The law’s requirements for data localisation, strict real-name verification, and for companies to provide the government with ‘technical assistance’ (possibly digital backdoors) on request strongly disadvantages foreign tech companies — although Facebook is trialling censorship mechanisms that might allow it back in. Xinhua 新华 lauded the passage of the law and hailed Xi as an ‘Internet Sage’ 网络达人 who has mustered the troops to fight for China’s Internet future. Among those ‘troops’ are some of the world’s biggest tech and Internet companies (including Huawei 华为 as well as Baidu, Tencent, and Alibaba, all of which are expanding their international clout. Gone are the days when Chinese authorities needed Cisco to help it build the Great Firewall.

The Yarovaya Law refers to a pair of Russian federal bills passed in 2016 that tighten counter-terrorism and public safety measures in Russia. It is known to the public under the last name of one of its creators — Irina Yarovaya

Image: en.kremlin.ru

At occasions such as meetings of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers and the Ten-Year Review of the World Summit on the Information Society (see Chapter 8 ‘Making the World Safe (for China)’), Beijing has defied the ideal of a unified, borderless web, asserting instead the concept of ‘cyber sovereignty’ — a concept that appeals to a number of authoritarian regimes around the world. In November, reports surfaced that Chinese officials and Huawei executives were in conversation with Russian officials about selling the data storage technologies needed to implement the Yarovaya Law, which requires companies to store data about Russian citizens within Russia and mirrors China’s own data localisation drive. Other governments, including Iran, Egypt, and Cambodia have expressed interest in similar Chinese technology that would help them assert control over its own cyberspace. Chinese netizens joked about the Chinese government is bundling Internet control with other popular Chinese exports: ‘buy a high-speed rail and we’ll throw in a Great Firewall for free’ 买高铁送防火墙.

During last year’s Paris terrorist attacks, the Chinese media contrasted the peaceful, calm space of the Chinese Internet to such foreign platforms as Twitter and Instagram, where radical jihadists may organise and recruit. The message had resonance beyond China. Even in the West, confidence in the idea of a ‘free web’ has given way to concerns over just how free might be too free. During the US election season, experts and policymakers fretted that online ‘fake news’ 虚假新闻, Internet trolls, and Russian bots were sowing chaos on the country’s much-vaunted free web. Most American commentators would likely be surprised to hear that China has been combatting ‘fake news’ and ‘clickbait’ or ‘sensationalist headline writers’ 标题党 for years. Not to mention that the Party is always on guard against ‘hostile foreign forces’ 敌对外国势力, especially in cyberspace. Increasingly, China’s model of Internet control looks like a bellwether of the Internet’s future. Maybe jello can be nailed to a wall after all?

Notes

‘Lu Wei: The Internet must have brakes’, China Digital Times, 22 September 2014, online at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2014/09/lu-wei-internet-must-brakes/

‘Address by Bill Clinton at John Hopkins University’, The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, 8 March 2000, online at: http://www.techlawjournal.com/cong106/pntr/20000308sp.htm

‘The Great Firewall of China: background’, Torfox: A Stanford project, 1 June 2011, online at: https://cs.stanford.edu/people/eroberts/cs181/projects/2010-11/FreedomOfInformationChina/the-great-firewall-of-china-background/index.html. See also, Geremie R. Barmé and Sang Ye, ‘The Great Firewall of China’, Wired, 6 January 1997, online at: https://www.wired.com/1997/06/china-3/, and James Fallows, ‘The connection has been reset’, The Atlantic, March 2008, online at: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2008/03/the-connection-has-been-reset/306650/

Paul Mozur, ‘U.S. adds China’s Internet controls to list of trade barriers’, The New York Times, 7 April 2016, online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/08/business/international/china-internet-controls-us.html

‘Apple’s help to China cited by U.S. in locked iPhone case’, Bloomberg, 10 March 2016, online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-03-10/government-strikes-back-at-silicon-valley-s-support-for-apple

‘What Apple did and didn’t do when China knocked on its backdoor’, Newsweek, 28 February 2016, online at: http://www.newsweek.com/2016/03/11/what-apple-do-when-china-knocked-backdoor-430993.html

Rebecca MacKinnon, ‘China’s censorship 2.0: how companies censors bloggers’, First Monday, vol.14, no.2 (2009), available online at: http://journals.uic.edu/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2378/2089 ‘

Xu Lin replaces Lu Wei as head of cyberspace authority’, Xinhuanet, 29 June 2016, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-06/29/c_135475896.htm

‘Shanghai’s Municipal Party Leadership Committee has four news faces: Xu Lin receives the most attention 上海市委领导班子现四张新面孔 徐麟最受关’, Xinhuanet, 29 June 2016, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2007-05/29/content_6169419.htm

‘Full text of Xi Jinping’s 19 August speech: Dare to take the opportunity to seize control and unsheathe the sword 网传习近平8•19讲话全文:言论方面要敢抓敢管敢于亮剑’, China Digital Times, 4 November 2013, online at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/chinese/2013/11/网传习近平8•19讲话全文:言论方面要敢抓敢管敢/

‘Celebrity Charles Xue Biqun released on bail’, South China Morning Post, 17 April 2014, online at: http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1484894/celebrity-blogger-charles-xue-biqun-admits-weibo-fuelled-his-ego

Yaqiu Wang, ‘Read and delete: how Weibo’s censors tackle dissent and free speech’, Committee to Protect Journalists, 3 March 2016, online at: https://cpj.org/blog/2016/03/read-and-delete-how-weibos-censors-tackle-dissent-.php

Jamil Anderlini, ‘Beijing warns Sina to “improve” censorship’, The Financial Times, 11 April 2015, online at: https://www.ft.com/content/0ab8ddba-e0dd-11e4-8b1a-00144feab7de

https://netalert.me/harmonized-histories.html

‘Lu Wei answers Beijing News’ question: why is it you can be looking at a post and then it just disappears? 鲁炜答新京报提问“为什么网帖看着看着就没了” ’, Beijing News, 9 December 2015, online at: http://www.bjnews.com.cn/news/2015/12/09/387299.html?from=singlemessage&isappinstalled=0

‘In 2016, the CAC took the lead in launching “cleansing” special actions — pointing the sword at internet malaise has sustained deterrence 2016年国家网信办牵头开展“清朗”系列专项行动剑 指 网络顽疾 形成持续震慑’, China Business News, 25 November 2016, online at: http://money.163.com/16/1125/16/C6NTLJQU002580S6.html

For a translation of Lu Wei’s speech ‘Foster Good Netizens, Build a Safe Net Together’, see: https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2015/06/08/foster-good-netizens-build-a-safe-net-together/

‘Alibaba’s Jack Ma urges China to use data to combat crime’, Bloomberg, 23 October 2016, online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-10-24/alibaba-s-jack-ma-urges-china-to-use-online-data-to-fight-crime. For the full transcript of Ma’s speech, see: ‘Full version: Jack Ma’s speech from yesterday oods internet, all the things no one’s talking about is here! 【正版】马云昨天的讲座刷屏了,网上没发的都在这里!’, Sohu, 22 October 2016, online at: http://www.sohu.com/a/116846985_355713

‘Lu Wei’s speech at the Initiation Ceremony for the Second National Cybersecurity Propaganda Week 鲁炜在第二届国家网络安全宣传周启动仪式上的致辞’, CAC Website, 1 June 2015, online at: http://www.cac.gov.cn/2015-06/01/c_1115464050.htm. Find a translation of the text online at: https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2015/06/08/foster-good-netizens-build-a-safe-net-together/

‘China Internet star Papi Jiang promises “corrections” after reprimand’, BBC News, 20 April 2016, online at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-36089057

‘Camgirl sentenced to 4 years in prison for broadcasting ‘obscene’ videos online’, Shanghaiist, 25 November 2016, online at: http://shanghaiist.com/2016/11/25/cam_girl_prison.php

‘Translation: Game developers lament censors’ demands’, China Digital Times, 9 December 2016, online at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/12/translation-game-developers-lament-censors-demands/

‘Starting China’s “Golden Age” of Internet culture 开启中国互联网文化的“黄金时代” ’, People’s Daily, 14 December 2015, online at: http://culture.people.com.cn/n1/2015/1214/c87423-27927090.html

Edward Wong and Vanessa Piao, ‘China cracks down on news reports spread via social media’, The New York Times, 5 July 2016, online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/06/world/asia/china-internet-social-media.html

Xi Jinping’s full speech at the Work Conference for Cybersecurity and Informatisation 习近 平在网信工作座谈会上的讲话全文发表, Xinhuanet, 19 April 2016, online at: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-04/25/c_1118731175.htm. Find a translation of the speech online at: https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2016/04/19/speech-at-the-work-conference-for-cybersecurity-and-informatization/

Daniel Cooper, ‘China’s new cybersecurity laws are a nightmare’, Engadget, 7 November 2016, online at: https://www.engadget.com/2016/11/07/china-s-new-cybersecurity-laws-are-a-nightmare/

‘Translation: Xi Jinping, Internet sage’, China Digital Times, 19 November 2016, online at: http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2016/11/translation-xi-jinping-cyber-sage/

‘China’s new cybersecurity law sparks fresh censorship and espionage fears’, The Guardian, 7 November 2016, online at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/07/chinas-new-cybersecurity-law-sparks-fresh-censorship-and-espionage-fears

‘Fang Kecheng: Diplomacy is the point of China’s World Internet Conference 方可成:“外交”是 中国举办“世界互联网大会”的本质’, The Initium, 18 December 2016, online at: https://theinitium.com/article/20151218-opinion-world-internet-conference-foreign-policy-fangkecheng/. A partial translation of the text can be found here: http://cmp.hku.hk/2015/12/21/39527/