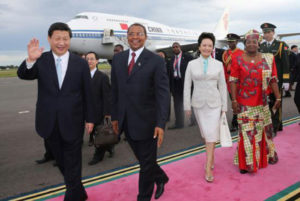

Just ten days after becoming President in March 2013, Xi Jinping, for the first leg of his first official visit abroad, visited Tanzania, South Africa, and the Democratic Republic of Congo — an acknowledgement of the importance of Sino-African relations to China. In December 2015, during the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation in South Africa, Xi announced that China aims to provide US$60 billion finance, to African nations over a three-year period to finance construction, mining, agriculture, and industrialisation projects across the continent. In September 2016, in his opening speech to the G20 Summit in Hangzhou, Xi reiterated China’s commitment to promoting industrialisation in Africa, and to boosting trade and investment between China and its African partners. Chinese trade and investment in Africa, alongside cultural exchange with the region, has already increased dramatically over the past three decades: China is now Africa’s largest trading partner (US$385 billion in two-way trade in 2015). It is also the fourth largest foreign direct investor in the region.

Chinese investment in Africa has benefited some African countries by creating jobs, injecting capital into cash-starved economies, and opening markets back in China for African agricultural and mining products. But there have been controversies as well, especially about the environmental cost of these investments.

The Case of Zambia

Zambia is a case in point where the environmental practices of some Chinese investment in the country have drawn criticism from the government, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and other commentators. In 2016, China’s Ambassador to Zambia announced that the total value of Chinese investment in the country had grown to over US$5.2 billion. Zambia is rich in copper, lead, and zinc, and has deposits of uranium, coal, and gemstones. Chinese foreign direct investment there, which spans finance, mining, agriculture, construction, education, and real estate, grew from US$6 million in 2000 to more than US$292 million by 2012.

Much of this investment was in the mining and construction sector. The Zambia Development Agency — a public agency established in 2006 to facilitate trade and investment in Zambia — claims that these Chinese investments have created jobs, rehabilitated old mines, opened new mines, constructed roads, and generated tax revenue for Zambia’s government.

However, there are concerns over the environmental impact of Chinese investments, especially in mining, hydropower, roads, and smelters. Some local environmental NGOs accuse Chinese mining companies of serious pollution of air, water, and land; damaging wildlife habitat and displacing local communities without adequate compensation. In 2013, Citizens for Better Environment (a local NGO), criticised two Chinese companies Nonferrous China Africa (NFCA) and Chambishi Copper Smelter (CCS), both based in the Copperbelt province, for failing to comply with local environmental regulations, including the timely submission of emissions and other environmental impact reports to the Zambia Environmental Management Agency (ZEMA) — the public body entrusted with the enforcement of local environmental regulations. Chinese companies are not the only ones to stand so accused regarding environmental pollution in Zambia: in 2016, 1,826 Zambian villagers living around the banks of the Kafue River in Zambia’s Copperbelt province took the UK’s Vedanta Resources to court in the UK for environmental damage that, they said, had turned their water supply into ‘rivers of acid’.

Zambia has a long history of poor environmental management, especially in mining areas. Its environmental regulation is relatively weak compared with those in developed countries such as Australia and Canada (which also have significant mining activities), and the government has been, historically, inattentive to calls for environmental protection in mining communities. What is more, Zambia’s previous mining regulations, such as the Mining and Mineral Development Act of 1996, and the development agreements signed between foreign mining companies and the Zambian government, protected mining and mineral processing companies against financial liabilities that might arise from legal suits by local communities for environmental damage.

Some officials at Citizens for Better Environment and the Zambia Institute for Environmental Management (ZIEM) — another local environmental NGO — argue that Chinese investment in Zambia (as in most African countries) has negatively impacted on the health of local communities, rivers, wildlife, and agriculture, and further weakened ZEMA’s ability to do its job. Some scholars, such as Dan Haglund, contend that Chinese companies have little incentive to comply with Zambia’s regulations because neither Chinese banks nor the government has the framework to monitor compliance by Chinese companies with the host country’s regulations, and because their managerial ethics emphasise productivity and profits above all else. Worse still, it is widely believed that Chinese managers are prone to bribing regulatory officials in Zambia, and that they use the threat of shutting down the mines (and subsequent job losses) to control or ‘capture’ Zambia’s government officials into turning a blind eye to their damaging environmental practices. Former Zambian president Michael Sata made Chinese investment in Zambia the centre of his 2006 presidential campaign, as he accused Chinese investors of non-compliance with local Zambian laws and the Levy Mwanawasa government of failing to address what he referred to as poor practices among the Chinese.

Another Side to the Story

But things are not always as they seem. Based on evidence gathered during my fieldwork in Zambia and my ongoing research on this topic, the views cited above are over pessimistic. Despite perceptions of regulatory weakness, over the past two decades the Zambian government has, in fact, introduced a number of measures to strengthen the country’s environmental laws. In 2007, it developed a National Environmental Policy to enhance the monitoring and enforcement capacity of local environmental agencies through increasing funding, revising environmental regulations, promoting coordination among relevant agencies, and increasing the fines for polluters, with the goal of boosting compliance from business, government, and individuals. In 2011, it passed the Zambian Environmental Management Act that created ZEMA, which replaced the Environmental Council of Zambia. In 2015, it passed the Mines and Mineral Development Act, prescribing stringent measures against mining companies that pollute the environment. These changes have forced companies, including those from China, to be accountable to government and local communities for their actions that affect the environment.

In line with this new regulatory regime, the Zambian government has suspended the mining operations of some Chinese companies, and collaborated with others to improve their environmental standards. For example, in December 2013, ZEMA suspended the operations of the Non-Ferrous China Africa (NFCA) Southeast Ore Body (SEOB) in Chambishi, Copperbelt province for two weeks because the company had failed to properly compensate and resettle communities affected by the SEOB project. The matter was resolved after NFCA agreed to compensate some members of the community who had formal legal claims to the land. That same year, ZEMA suspended operations at Chambishi Copper Smelter because the smelter was releasing emissions above ZEMA statutory limits. In 2015, ZEMA suspended mining operations at Chinese Copper Mining in Chingola after some residents of the township accused the company of ‘polluting their environment and some streams from which local people were drawing water’.

While most of these suspensions were temporary, they nevertheless led to changes at both NFCA and CCS. For instance, CCS hired Citizens for Better Environment (CBE) to monitor its emission levels and report them to ZEMA as required by law. NFCA developed a program to compensate communities affected by its mining activities. According to its Chief Executive Officer, Wang Chunlai 王春来, NFCA lost US$10 million as a result of the suspension. The company also created a new Department for Safety and Environmental Management, with an assistant director for environment, to ensure that NFCA complies with local environmental laws.

Other constraints on Chinese companies operating in Zambia come from NGOs and community groups, such as farming communities. Local NGOs have taken Chinese mining companies to court for financial compensation and they have conducted independent assessments of the environmental impact of mining projects that local residents have deemed to be polluting the local environment.

For instance, in 2011, the Zambia Institute for Environmental Management (ZIEM) — a members-based NGO whose partners include the Ministry of Lands, Natural Resources, and Environmental Protection and the University of Zambia as well as Oxfam, Action Aid, and other international organisations — conducted an Environmental Social Impact Assessment for a mine operated by the NFCA, in the Musakashi River Catchment Area. The project exposed shortcomings in NFCA’s management of wastewater, and also found that the mine’s acid emissions had damaged crops, aquatic life, houses, and roads. The mine agreed to improve its waste storage and processing facilities, and to compensate some of the affected farmers.

In another case, in 2014, CBE, acting on behalf of the Luela Community farmers of Chambishi in Kalulushi District, sued CCS in the Kitwe High Court for damages caused to local farms. The case was settled out of court. The company agreed to compensate the affected farmers, and hired CBE to monitor its emission levels on an ongoing basis.

The Big Picture

The Chinese government and Chinese companies are developing strategies to reduce environmental damage caused by overseas operations. In 2013, China’s Ministry of Commerce 商务部 and Ministry of Environmental Protection 环境保护部 released a document titled, ‘Guidelines on Respecting Overseas Environmental Standards and Managing the Environment’. This and other official documents stress the need for Chinese companies to comply with the environmental standards of the countries in which they operate. According to Lin Songtian 林松添, Director General of the Department of African Affairs at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Chinese ‘government did not want to see African countries following the path of pollute first and clean up later’.

The environmental challenges brought by Chinese investment in Zambian mining and the evolving means by which they are addressed should also be seen as part of a larger and dynamic relationship. Chinese investment in most African countries comes with both costs and benefits. Thus, the rise of Chinese investment in Africa is not inevitably harmful to local economies. In the case of Zambia, both sides have shown efforts to address negative environmental effects, among other public concerns, and are expanding their collaborative efforts in these area. Nonetheless, as China continues to deepen its economic ties with Africa, social concerns associated with the growing economic presence of China in the region, and how these concerns are addressed, will continue to influence Sino-African debates in the near future.

Notes

All the figures are drawn from my thesis, Beyongo Mukete Dynamic, Regulating Chinese investment in Zambia — resisting a race to the bottom?, doctoral thesis, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, 2017.

Interview by the author with officials in charge of foreign direct investment at Zambia Development Agency, 24 July 2015.

Matthew Hill, ‘Zambia’s Chambishi Smelter to reopen, environmental regulator says’, Bloomberg, 14 February 2013, online at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-02-14/zambia-s-chambishi-smelter-to-reopen-environment-regulator-says

‘ZEMA queried over Chambishi’, Lusaka Voice, 18 February 2013, online at: http://lusakavoice.com/2013/02/18/zema-queried-over-chambishi/

‘High Court allows group claim to proceed against UK-domiciled parent company in relation to acts of subsidiary company abroad’, Litigation Notes, Herbert Smith Freehills, 13 June 2016, online at: http://hsfnotes.com/litigation/2016/06/13/high-court-allows-group-claim-to-proceed-against-uk-domiciled-parent-company-in-relation-to-acts-of-subsidiary-company-abroad/

D. Haglund, ‘Regulating FDI in weak African states: a case study of Chinese copper mining in Zambia’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, vol.46, no.4 (2008): 547–575.

Chris Mfula and MacDonald Dzirutwe, ‘Zambia’s “King Cobra” Sata sworn in as president’, Reuters, 23 September 2011, online at: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-zambia-election-idUS- TRE78M1L820110923

‘ZEMA stops NFCA from mining in Chambishi’, Lusakatimes, 4 December 2013, online at: https://www.lusakatimes.com/2013/12/04/zema-stops-nfca-mining-chambishi/

‘Chinese company defies court’, Daily Nation, 28 October 2015, online at: https://zambiadailynation.com/2014/03/20/chinese-company-defies-court/

‘NFCA Chambishi mine sets aside US$100 million for SEOB-report’, Zambia Mining Magazine, 27 February 2014, online at: http://www.miningnewszambia.com/nfca-chambishi-mine-sets-aside-us100-million-for-seob-report/

Zambia Institute of Environmental Management, August 2013, Key messages on Environmental and Social Impacts Assessment for Musakashi River Catchment Area, online at: http://media.wix.com/ugd/995bdc_6ed4df3e3f504a22a6912727b9c90861.pdf

Citizens for Better Environment v. Chamsbihi Copper Smelter, 2013/HK/55 (Kitwe High Court, 18 April 2013).

Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, ‘Notification of the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Environmental Protection on Issuing the Guidelines for Environmental Protection in Foreign Investment and Cooperation’, 1 March 2013, online at: http://english.mofcom.gov.cn/article/policyrelease/bbb/201303/20130300043226.shtml

David Shinn, ‘Environmental impact of Chinese investment in Africa’, Cornell International Law Journal, vol.49 (2016): 41