When American swimmer Michael Phelps won a gold medal at the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio, news of the strange, purplish polka dots across his shoulders raced around the world. International press featured reports on the medical treatment of cupping, increasingly popular among Olympians to aid their recovery from strenuous training. The media discussed the resemblance of these spots to love bites (both are created by suction), their value as a fashion statement (celebrities such as Gwyneth Paltrow and Victoria Beckham have been sporting them as well), and the pros and cons of cupping as medicine. Advocates of alternative medicine claim that, among other things, it detoxes the body, improves blood circulation, cures skin conditions and respiratory ailments, and boosts autoimmune response. David Colquhoun, professor of pharmacology at University College London, has described such claims as ‘desperately implausible’, though. He told The Independent: ‘There’s no science behind it whatsoever. There’s some vague conceptual connection with acupuncture, and is often sold by the same people. But how could it possibly do anything? It’s nonsense.’

Meanwhile in China, cupping was at the centre of one of 2016’s biggest medical controversies, which was spurred by the death on 7 September of the popular twenty-six-year-old film and television actress and blogger Kitty Xu Ting 徐婷. Xu had T-cell lymphoma, but chose to forego chemotherapy for a course of cupping and other traditional medicinal treatments. Her death spurred a lively and anguished debate on Chinese social media about the relative advantages of and the relationship between Chinese and Western therapies.

Cupping is a part of traditional Chinese medicine. It is ubiquitous in China; you can find ‘The art of the pulling cup’ 拔罐疗法 practiced at medical clinics 诊所, 国医堂, in the small medicine shops of the bonesetters 国术馆, and massage parlours 按摩院, 美容院 or even by curbside folk healers. As a delightful result of cross-cultural fertilisation, traditional Chinese cupping services are now also offered as part of a ‘Roman bath’ 罗马浴场. Practitioners use it to alleviate an array of disparate conditions ranging from muscular strains to migraines to indigestion, to name a few. In fact, it was not so long ago that Western doctors also practiced cupping. Yet that memory has vanished so completely that people today speak of it as a novel introduction from the ‘East’.

Both Eastern and Western traditions of cupping use similar techniques, and practice both dry and wet cupping (termed ‘static’ 留观法, 坐观法 and ‘blood pricking’ 刺血拔罐法 in Chinese). In dry cupping, heat or an air pump is used to create suction inside the cup, which pulls the skin up and away from the underlying muscles for five to fifteen minutes. The suction breaks some of the blood vessels, which causes the tell-tale circular bruises to appear. In the case of wet cupping, skin and underlying capillaries are perforated with a small lancet first, and thus a small amount of blood is let. In China, a further variant, ‘moving cupping’ 走罐法,推观法, where suction cups are slid along anointed skin, and which is more closely related to traditional Chinese massage 推拿, is also used. Historically, cupping was done with gourds (cucurbita) 南瓜, clay cups, animal horns 角法 or bamboo pipes 吸筒法. The latter are still used by some cuppers in China today.

According to traditional Chinese medicine, cupping drains blood and qi stagnations 瘀血,氣結 and flushes out external pathogens 邪,寒,风 that may have invaded the body. Experienced cuppers locate the places of stagnation with precision and draw from them livid blood. Western humoralism was based on the conception of a fluid body that is composed of humours — phlegm, bile, black bile, and blood — that threatened to putrefy when they were in excess or ceased to flow and needed constant vigilance and manipulation to preserve the body’s health. In this tradition, the practice of cupping is held to purge the body of putrid humors and plethora (excess blood), thought to cause such ailments as fevers, infections, gout or arthritic pain. In both traditions, cupping functions as mild evacuation therapy — that is, a gentle form of letting blood, comparable to the once widespread practice of leeching.

Early descriptions of bloodletting in Chinese medicine are found in the Plain Questions 素問 part of the foundational Classic of Chinese medicine, the Classic of the Yellow Emperor 皇帝內经 (first century BC). They prescribed draining the blood from specific pain-related sites with lancets made from stone. Intriguingly, the Hippocratic Treatises (fifth-to-fourth century BCE) describe comparable site-specific bloodletting. In both traditions, these sites were located along isolated pathways that did not map onto later conceptions of qi meridians in China, or anatomical locations of the arteries in Greece. They could be quite far from the locus of the pain itself, such that Galen of Pergamon (129–c.210AD), for example, bled the inside of the ankles to relieve testicular pain.

A) Full-sized scarificator; B) ditto for the perineum; C) small temple scarificator; D) spirit bottle; E) torch tube, unscrewing in the middle: Western medicine

Source: Hill, A treatise on the operation of cupping (London, 1839)

In both traditions, site-specific bloodletting largely disappeared after the classical period. In Greco-Roman medicine, it diverged into general and topical bleeding — that is, phlebotomy, or the practice of dis-localised bleeding by means of venesection, and superficial bleeding, such as cupping, leeching, or scarification. In Chinese medicine, site-specific bleeding evolved into acupuncture, in which fine needles are inserted into precisely defined points along the pathways (脉,经络) of qi. This practice involves draining qi rather than blood.

Yet cupping persisted in both China and the West. In China, it was mostly a folk practice, outside the scope of the written tradition, though learned physicians from the Tang to the Yuan dynasties occasionally recommended ‘pricking veins’ 刺络 or ‘releasing blood’ 放血 , and Qing dynasty compendia, such as the Supplement to the Outline of Materia Medica 本草纲目拾遗, document the technique of ‘fire cupping’ 火罐气 in greater detail. In Western medicine, topical bleeding and phlebotomy declined over the nineteenth century, despite the publication in the early part of that century of quite a number of learned treatises on the art of cupping, as well as technical innovations such as the ‘mechanical scarificator’, which made incisions more precise and less painful.6 The rise of an energetic conception of body in conjunction with the discovery of medicinal chemical compounds led to the gradual demise of humoralism and provided powerful alternatives to the practice of evacuation therapies. But cupping was still being applied for pneumonia into the twentieth century. In ‘How the Poor Die’, George Orwell described a personal experience of the practice in the public ward of a Paris hospital in 1929:

First the doctor produced from his black bag a dozen small glasses like wine glasses, then the student burned a match inside each glass to exhaust the air, then the glass was popped on to the man’s back or chest and the vacuum drew up a huge yellow blister. Only after some moments did I realize what they were doing to him. It was something called cupping, a treatment which you can read about in old medical text-books but which till then I had vaguely thought of as one of those things they do to horses. The cold air outside had probably lowered my temperature, and I watched this barbarous remedy with detachment and even a certain amount of amusement.

The next moment, however, the doctor and the student came across to my bed, hoisted me upright and without a word began applying the same set of glasses, which had not been sterilized in any way.

The current cupping hype — along with enthusiasm for other evacuation therapies, such as leeching or colonic irrigation — suggests that ancient fears of festering humours and the compulsion to purge are making a come back in thinly disguised form of ‘toxins’ and ‘detoxification’. Yet Western amnesia of the most basic practices of European medical heritage and the mystique of Chinese medicine are such that not only medical doctors like David Colquhoun, but even aficionados such as Gwyneth Paltrow — who has been using cupping for at least ten years — ignore the fact that less than one hundred years ago, it was still practiced in Europe. As Paltrow states: ‘Eastern medicine has a different approach than [sic] Western medicine — it’s more holistic’. While she would likely cringe at the thought of undergoing phlebotomy, she seems blissfully unaware that her therapy of choice is precisely that: a mild form of bloodletting. Granting efficacy to humoral therapies seems ludicrous to most, but many seem willing to allow for their effectiveness as long as they perceive them as Chinese medicine. Yet history shows that cupping is a revival of Western humoralism as much as it is an alluring tradition from the East.

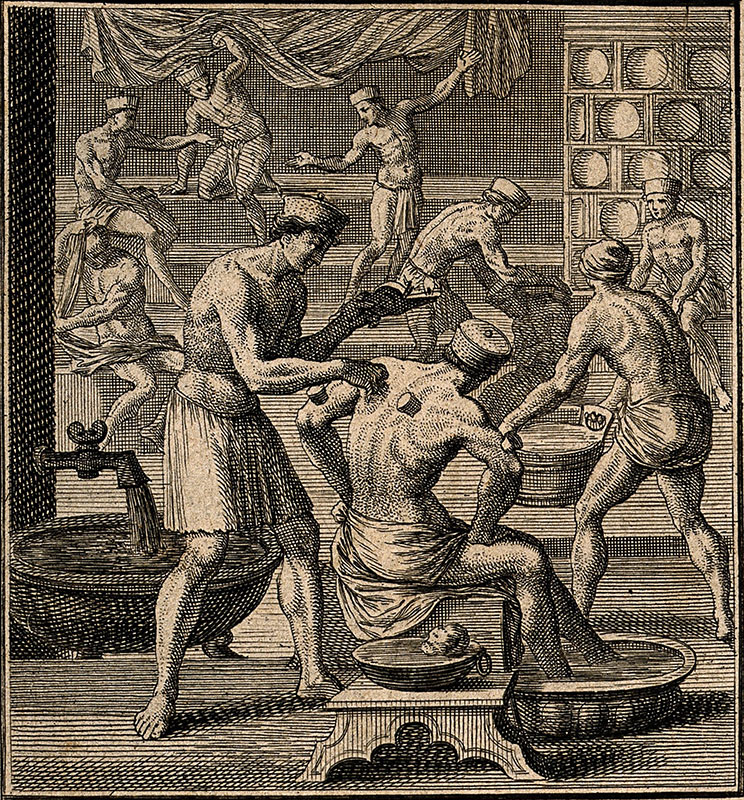

Historical illustration of a cupping session in a German bathhouse

Source: Wellcome Library, London. Engraving by C. Luyken (?)

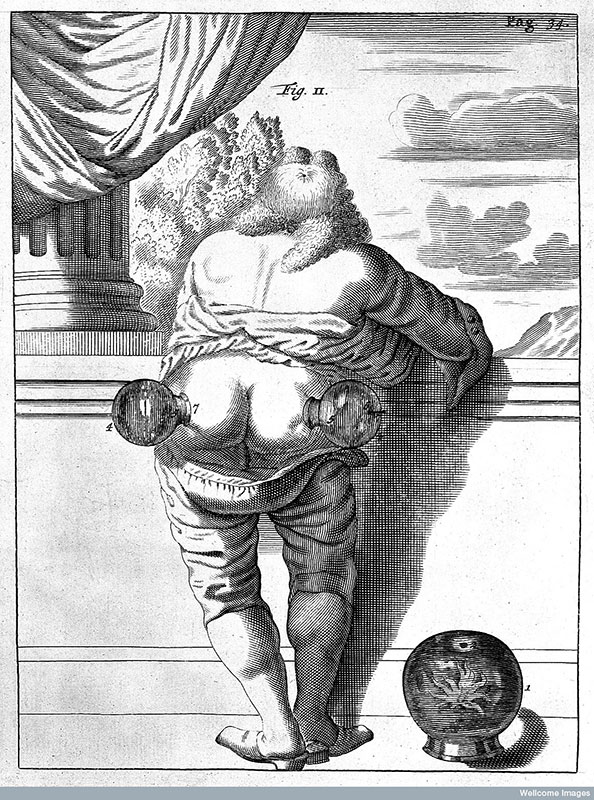

Seventeenth-century buttock cuppping, taken from Exercitationes practicae circa medendi methodum, auctoritate, ratione, observationibusve plurimis confirmatae ac figuris illustratae

Source: Wellcome Library, London. Engraving by Frederik Dekkers.

Notes

Harry Cockburn, ‘Rio 2016: What is “cupping” and why are Olympic athletes doing it?’, The Independent, 8 August 2016, online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/rio-2016-cupping-what-is-it-olympics-athletes-suction-cups-skin-marks-a7178731.html

Chiara Palazzo, ‘Chinese actress’s death sparks national debate over Chinese medicine’, The Telegraph, 16 September 2016, online at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/09/16/chinese-actress-death-sparks-national-debate-over-traditional-me/

Subhuti Dharmananda, ‘Cupping’, online at: http://www.itmonline.org/arts/cupping.htm

Shigehisa Kuriyama, ‘Interpreting the history of bloodletting’, The Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol.50, no.1 (1995): 19; and Henry McCann, Pricking the Vessels: Blood- letting Therapy in Chinese Medicine, Philadelphia: Singing Dragon, 2014.

Shigehisa Kuriyama, ibid: 11–46; and D.C. Epler, ‘Bloodletting in early Chinese medicine and its relation to the origin of acupuncture’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, vol.54, no.3 (1980): 337–367

J.S. Haller, ‘The glass leech: wet and dry cupping practices in the nineteenth century’, New York State Journal of Medicine, vol.73, no.4 (1973): 583–92; and Thomas Mapleson (Cupper to his His Royal Highness the Prince Regent), A Treatise on the Art of Cupping in which the History of that Operation is Traced, the Complaints in which it is Useful Indicated, and the Most Approved Method of Performing it Described, London: 1813; and William Brockbank, Ancient Therapeutic Arts. The Fitzpatrick Lectures delivered in 1950 & 1951 at the Royal College of Physicians, London: William Heinemann Medical Books Ltd, 1954.

George Orwell, ‘How the poor die’ in Orwell Reader: Fiction, Essays, and Reportage (San Diego: Harcourt, 1946), pp.86–87.

Gwyneth Paltrow, ‘The healing power of acupuncture’, Goop, online at: http://goop.com/healing-power-acupuncture/