PRESIDENT XI JINPING’S SPEECH on 1 October 2019 in celebration of the seventieth anniversary of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) ended with the following appeal to ‘all comrades and friends’:

While China’s past has already been written into the history books of humanity, China’s present is being created by hundreds of millions of people and it is inevitable that China’s future will be even more beautiful. All Party members, all members of the armed forces and the people making up the various nationalities of our country must be even more closely united. We must never forget our original intention, we must keep our mission firmly in mind, we must continue to consolidate our achievements and develop well our People’s Republic. We must continue the struggle to realise the goal of the ‘Two Centuries’ and we must also struggle hard to realise the China Dream of the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation!1

Even among people who grew up in mainland China or live there today, a large majority may have only a vague understanding of the meaning of opaque expressions such as ‘our original intention’, ‘the goal of the “Two Centuries” ’ and ‘the China Dream of the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation’. Nonetheless, for Chinese citizens, regardless of how much or how little they understand the slogan-saturated language used in speeches by Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders, this language is an unavoidable part of everyday life. They encounter it from the time they enter kindergarten and thereafter throughout their formative years, daily in the media, and in the workplace. The Party’s slogans, songs, and spectacular national day parades, and the images and stories it projects of China’s past and present, are interwoven into people’s memories of school life and public holidays.

This enforced familiarity with the Party’s language is essential for understanding the China Dream as a signature idea of Xi’s administration. It is perhaps more important to pay attention to what the China Dream does — how the term operates and what it enables — rather than what it means. For one thing, the tifa 提法 (prescribed formulation) in which the China Dream appears tells us that the term relates to the Party’s avowed goal of achieving ‘the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation’. Comprehending the China Dream requires understanding of the CCP’s preoccupation with the use of tifa.

Linguistic Encumbrances

In everyday Chinese, tifa refers simply to how an idea or topic is commonly expressed. In the Party’s vocabulary, however, it signifies the (one) correct way (fa) of discussing an issue (ti). The term was first widely adopted as a tool of government during Mao Zedong’s time in power (1949–1976). The Party requires all PRC officials to adhere to the specific wording approved by the party leadership so that their public communications project a picture of ‘unwavering’ 不动摇 (a favoured party adjective) unity.2 While political parties everywhere undoubtedly want their members to speak with one voice, the CCP may severely punish individuals who do not ‘maintain a unified calibre’ 统一口径 — that is, stay on message.

While Mao lived, he wielded such power that his choice of words — also known as Mao Zedong Thought — became the only tifa that mattered. People accused of transgressing against Mao or Mao’s Thought ended up in jail, labour camps, or dead. The awe that Mao commanded in life, including the extreme cult of personality he enjoyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), made it impossible for his successors to consign Mao’s Thought to the past after his death in 1976. Deng Xiaoping and other Party leaders adjudged the Cultural Revolution ‘a catastrophic decade’ and implemented economic policies opposite to Mao’s. But Deng nonetheless asserted in 1980 that any attempt to discard ‘the banner of Mao Zedong Thought’ would be ‘nothing less than to negate the glorious history of our Party’. Every post-Mao administration, including Xi’s, has invoked Mao’s Thought even as it introduced new tifa to consolidate its own authority.

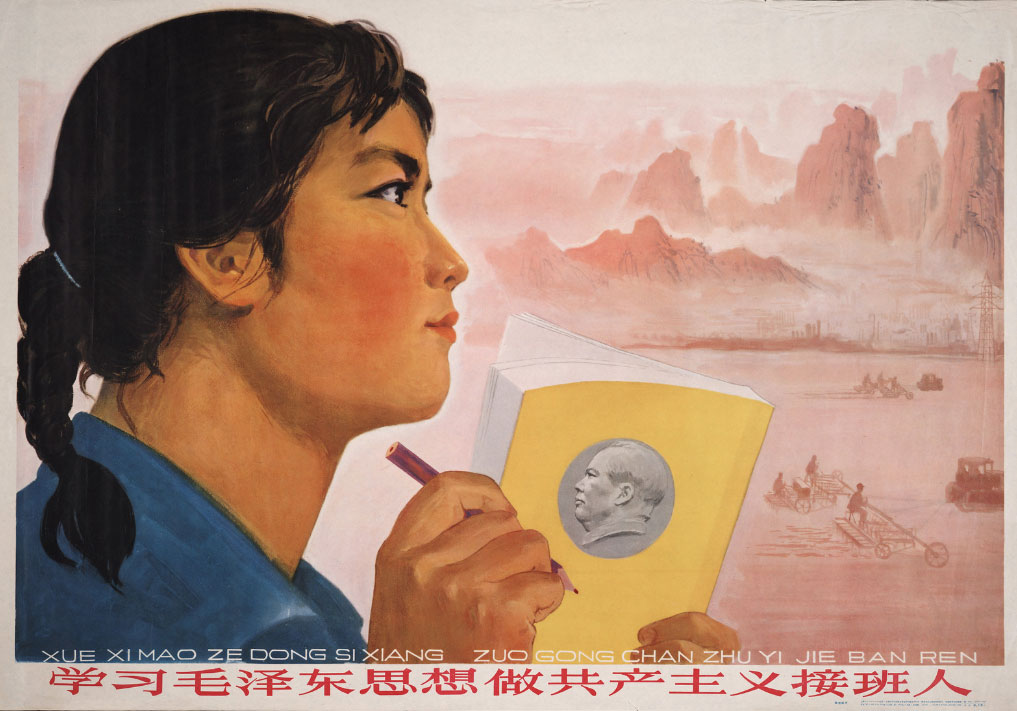

‘Study Mao Zedong Thought, Be the Sucessors of Communism’

Source: Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library UofT, Flickr

The use of tifa bears a distinct similarity to what Alexei Yurchak calls ‘hypernormalisation’ in his study of language use in the late Soviet Union. According to Yurchak, the leaders of post-Stalin administrations slavishly replicated formulations that had first enjoyed authority under Joseph Stalin, as if by clinging to established discursive norms they were demonstrating the Communist Party-state’s enduring legitimacy and their own fitness to rule as Stalin’s heirs. As social and cultural change gathered pace, however, the more the Party insisted on the authority of its ‘fixed and cumbersome forms of language’, the more the increasingly cosmopolitan Soviet citizenry on whom it had been imposed took to parodying it.3 Consequently, in the late 1980s, when Party leaders belatedly called for official communications to provide ‘real self-criticism’ and admit ‘real problems’, the Party’s language proved incapable of doing so convincingly; its hypernormality was too entrenched.4

Xi has used the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 to warn Party members against complacency regarding the CCP’s own future. He has stressed the importance of ‘strengthening ideological and political work’ to prevent a similar outcome in China. In a 2013 speech, he opined that former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev’s admission, in July 1991, that ‘Communist thinking had become obsolete for him’, signalled a decisively negative turn for the Soviet Union.5 Xi asked rhetorically: ‘When the spirit of conviction no longer exists, where is the core of a Party and a country?’6

Xi’s anxieties about waning faith in CCP rule hint at why he has adopted the China Dream as his watchword. ‘Dream’, in the Party’s tifa — and unlike its more classical meanings (see Introduction Forum, ‘Zhuangzi and His Butterfly Dream: The Etymology of Meng 夢’, pp.11–14) — is synonymous with desire: people must want, or be taught to want, ‘the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation’, and they must also see this rejuvenation as achievable only under CCP rule. For this reason, Xi often juxtaposes two tifa featuring the ubiquitous Mao-era word ‘struggle’, using this word to signal fidelity to Communism’s ‘original intention’. As he stated in his 1 October 2019 speech: ‘We must continue the struggle to realise the goal of the “Two Centuries” and we must also struggle hard to realise the China Dream of the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation!’ The fact that ‘struggle’ in Mao’s time meant ‘class struggle’ — a cause his successors have long abandoned — is, tellingly, never mentioned.

The ‘Two Centuries’ refers to the upcoming centenaries of the CCP’s founding, in 2021, and that of the PRC, in 2049. The Party has publicly committed to achieving ‘moderate prosperity’ throughout China by 2021 and delivering ‘democracy, harmony, strength and wealth’ by 2049.7 Each of these goals comes with its own set of painstakingly formulated tifa, for they also form part of the Twelve Core Socialist Values launched at the Eighteenth National CCP Congress in November 2012, when Xi was inaugurated as the Party’s General Secretary. The constant reiteration of these Xi-era formulations in speeches, media articles, and commentary aims to demonstrate the Party’s clarity and unity of purpose and to instruct citizens how to resonate with the Party’s will in their own communications.

Propagating the China Dream

Censorship and propaganda go together. The China Dream is the propagandistic corollary of the harsh measures Xi’s administration has used since 2013 to rein in online parody of the Party’s language, which had spread throughout the 2000s and into the early 2010s. Previously, parodies took the form of ditties and jokes passed on through friendship networks; they had no hope of ‘going viral’. China’s Party leaders know that in the digital age, censorship is a poor tool for suppressing the expression of public discontent with Party-state rule. They have thus sought to win people over with their China Dream campaign. Individuals appearing in talent contests and reality TV programs — the favourite entertainment of a majority of mainland viewers — tend to speak effusively of their ‘dreams’. The China Dream provides a handy device for linking the Party-state’s goals to those of individuals.

On 23 March 2013, Xi nodded to this link when he said:

In the final analysis, the China Dream is the people’s dream for it is entirely dependent on the people for its realisation, and so this is a dream that must constantly work to benefit and enrich the people.8

State-run media regularly quotes this and other statements by Xi that highlight the intertwined nature of the China Dream and the dreams of individual Chinese citizens.

University of Sydney anthropologist Gil Hizi’s study of China Dream propaganda notes that, since 2013, the Party has employed both state-run and privatised initiatives to equate the CCP’s goals with the China Dream of delivering a good life to the people.9 Schools encourage students to write essays and make speeches about their personal dreams as part of the China Dream and several universities have held public speaking competitions on the theme of ‘China Dream, My Dream’.

State censorship and surveillance, coupled with the threat of severe penalties, have nearly succeeded in wiping out online ridicule of China Dream propaganda. On Bilibili, China’s leading video-sharing website, vox populi–style clips have appeared of people talking positively about the China Dream and what it means to them personally. The majority of comments on the videos are positive, with only a few users leaving sardonic remarks such as: ‘Watching this makes me think of this [meme]: “With a population of 1.4 billion, it’s no surprise there are some stupid c**ts in China. Do you think you’re living in a paradise?” ’10 Another user queried: ‘Shouldn’t the China Dream begin with a hard disk repair?’11

Conflation of propaganda and entertainment is integral to ideological strengthening under Xi. Analysing three televised public speaking contests revolving around the China Dream, Hizi writes that contestants in Super Speaker, I am Speaker, and Wonderful China — aired respectively in 2013, 2014, and 2015 — all told stories of personal triumph in the style of ‘filial nationalism’. They

echo the message of the China Dream by offering visions of the future through relying on a shared past. They bring into life an imaginary in which stability and reform, conformity and innovation, obedience and self-expression, are by no means antonymic concepts.12

A good example of the Party’s recent efforts at encouraging identification with CCP ideology through entertainment is The Leader 领风者, a cartoon series about the life and times of Karl Marx released for streaming on Bilibili on 28 January 2019. Made to commemorate the 200th anniversary in 2018 of Marx’s birth, this seven-episode series was an initiative of the Central Office for the Research and Construction of Marxist Theory 中央马克思主义理论研究和建设工程办公室. The Hangzhou-based animation company Wawayu TV produced the series with support from the Inner Mongolia branch of the Party’s Propaganda Department and the Inner Mongolia Film Group, which the Propaganda Department controls. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) and the Propaganda Department of the Communist Youth League were also involved in

the production.13

In The Leader, Communism’s founding father is depicted as tall, slim, and wide-eyed, with a high forehead, well-defined jawline, arched brows, and dark wavy hair — resembling any number of popular heroic male anime characters. The point was to ‘reinvent and broadcast Marxism as widely as possible, [to] bring Marx and Generation Z together’, as the title of a Guangming Daily editorial put it.14 However, an article published in the online magazine Sixth Tone pointed out that The Leader also had the unintended effect of leading viewers to pay ‘more attention to Marx’s high cheekbones and good looks than his theories’.15

The Guangming Daily editorial’s gushing endorsement of the cartoon series was to be expected. This newspaper is directly controlled by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department (CPD). The Shanghai-based Sixth Tone, conversely, is an English-language outlet owned by the Shanghai United Media Group, a commercial operation supervised by the Shanghai Committee of the CCP. Its primary audience is an international Anglophone readership. Sixth Tone’s good-humoured criticism of the cartoon series is characteristic of this outlet’s more sophisticated approach to ‘maintaining a unified calibre’ with the CPD. Self-described as covering ‘issues from the perspectives of those most intimately involved to highlight the nuances and complexities of today’s China’, Sixth Tone’s editors and writers ensure that the engaging content they publish never amounts to serious dissent.16

In a 2016 article about Sixth Tone’s equally readable Chinese-language sister publication, The Paper 澎湃, the China Media Project’s David Bandurski points out Xi’s description of effective propaganda in 2015 as being capable of extending its ‘tentacles’ to ‘wherever the readers are, wherever the viewers are’. He elaborates on Xi’s octopian metaphor:

Propaganda can no longer repulse, as it has so often done in the past, with its dead and colourless reports. It must attract. More to the point, it must attach. It must reach out to us and attach itself to us. Draw us in and lead us along. We must say: What a wondrous creature this is! Look at the way it lives and breathes, and coils itself around our lives!17

The injection of entertainment value into party ideology does not make it less coercive. If rigid and formulaic party tifa reflect a hypernormal — hence pathological — insistence on linguistic conformity to signify the Party’s lasting power, the use of anime, rap, and other forms of entertainment culture to exalt the Party turns everything into grist for the Party’s ideological mill. In an interview, Zhong Jun 钟君, a researcher at CASS and head writer for The Leader, likened the ‘revolutionary’ series to the work of intellectuals in the 1910s, whose self-declared ‘literary revolution’ brought modern standard Chinese into existence:

The transition from the premodern literary language [文言文 wenyanwen] to the modern vernacular [白话 baihua] was a revolution. Our adaptation of theoretical discourse into a language intelligible to the masses is similarly a revolution.18

Disfiguring May Fourth

The ‘literary revolution’ that took place from 1915 until the early 1920s was a cultural movement initiated by progressive intellectuals based at Peking University. These included, among others, the CCP’s two most prominent founders, Chen Duxiu 陈独秀 (then Dean of Arts at Peking University) and Li Dazhao 李大钊 (the university’s chief librarian), as well as Lu Xun 鲁迅 (China’s best-known twentieth-century writer, whom Mao posthumously lauded as ‘the sage of modern China’) and Hu Shi 胡适 (China’s foremost liberal thinker). These individuals despaired that even after the collapse of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) and the founding of the modern republic in 1912, China had failed to modernise. They vowed to eradicate everything ‘old’ that was holding Chinese society captive to the oppressive habits of its dynastic past. They espoused a New Culture (新文化 xin wenhua) that would deliver mass literacy through the nationwide adoption of a modern, plainspoken language (白话 baihua), based on the Beijing dialect. They perceived China’s difficult premodern literary language (文言文 wenyanwen) to be a tool of oppression, accessible only to the elite scholar-official class (as 士, 绅士, 士大夫, or 文人, shi, shenshi, shidaifu, or wenren). They hoped that baihua, as a language in which ordinary Chinese people could express themselves freely, would help to bring into existence a just and democratic society.

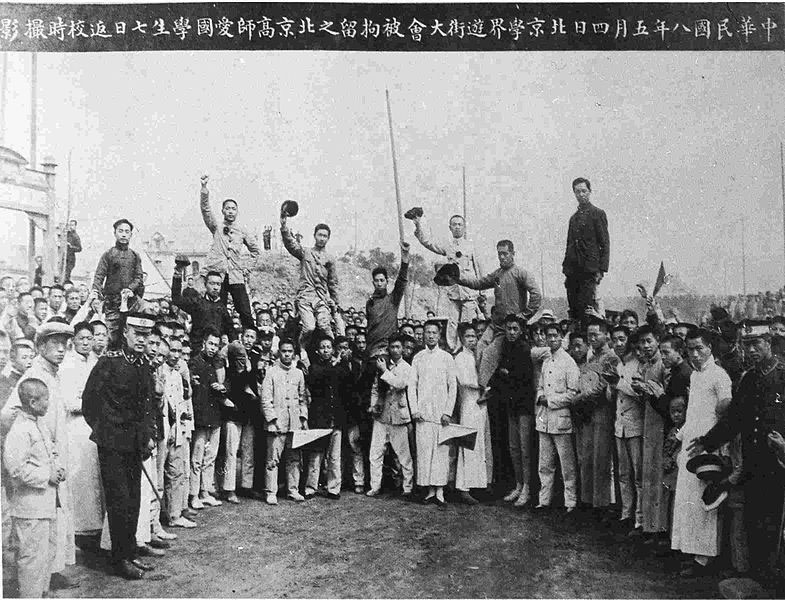

Students of Beijing Normal University returning to campus after being detained during the May Fourth Movement

Source: Sgsg, Wikipedia

Zhong’s comparison of the propagandistic cartoon The Leader with the New Culture advocacy of baihua as an egalitarian language that belongs to everyone may seem egregious. But ‘Make the past serve the present, make the foreign serve China’ 古为今用, 洋为中用 was one of Mao’s favourite sayings, and one that Mao’s successors have turned into an authoritative tifa. Xi, who has quoted this saying on several occasions, evidently sought to make the legacy of New Culture intellectuals serve his ends when he commemorated the centennial of the May Fourth Movement in 2019.

New Culture and ‘May Fourth’ 五四 are often used interchangeably, with the former being generally subsumed under the latter. Student activists of the New Culture movement initiated the historic street protest in Beijing on 4 May 1919. Sparked by the poor treatment China received at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, May Fourth expanded from a political protest to a national social and political movement that encompassed workers’ rights, women’s rights, and universal education. Mao’s 1940 description of May Fourth as the starting point of China’s ‘history of “cultural revolution” ’ has ensured the reverential observation of this anniversary in the PRC ever since. In Xi’s speech of 30 April 2019, he narrowed the significance of May Fourth to the patriotism shown by ‘progressive students and intellectuals’ who led ‘the broad masses’ in a ‘thoroughly anti-imperialist and anti-feudal great patriotic revolutionary movement’.19

Xi used these Mao-era tifa to evoke continuity with Mao while suppressing the discourse of ‘cultural revolution’ that these tifa originally served. Instead, he claimed that May Fourth offered ‘profound historical evidence’ of ‘patriotism flowing in the veins of the Chinese nation past and present, irremovably, indestructibly, and inextinguishably’. This ahistorical privileging of patriotism allows Xi to tie the achievements of May Fourth to those of the CCP under Mao, after Mao, and up to his own administration, as the workings of the same eternal ‘powerful spiritual force’.

Xi used his own tifa — ‘to realise the China Dream of the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation’ — six times (with minor variations), first in his opening paragraph and then as a concluding refrain to different sections of his speech. Coupled with his eleven other mentions of ‘great rejuvenation’ and twenty-eight references to the New Era (a temporal designation understood to mean Xi’s era, which began in October 2017 with the inauguration of ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’; see China Story Yearbook: Power, Chapter 2 ‘Talking (Up) Power’, pp.37–48), Xi effectively reduced May Fourth to a mere rhetorical device for exalting CCP rule under his stewardship. Of the twenty-eight references to New Era, twenty-two were to ‘Chinese youth in the New Era’ 新时代中国青年. Xi was, in this instance, emulating the celebration of youth in both New Culture writings and Mao’s speeches. He exhorted ‘China’s youth in the New Era’ to

continue developing the spirit of May Fourth, to take the realisation of the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation as their personal responsibility, to betray neither the Party’s and the people’s expectations of them nor the trust the nation has placed in them, and to never fail to live up to this great era of ours.

Party discourse is circular and self-referential because its function is to demonstrate that the Party’s word is law. Xi’s speech is no exception. The China Dream, so construed, cannot be meaningfully developed in open discussions. The function of a guiding tifa such as the China Dream, by virtue of its self-definition as a correct form of words, is to foreclose inquiry and reflection. Yurchak wrote of Party language in the Soviet Union that it generated ‘a peculiar paradox’: for a population habituated to authoritarian censorship and propaganda, ‘although the system’s collapse had been unimaginable before it began, it appeared unsurprising when it happened’.20

The propagation of the China Dream as each individual Chinese citizen’s dream is the remedy Xi hopes will prevent a similar collapse of Party rule in China. He is not offering citizens the freedom to discuss what dreams they can realistically achieve in a highly competitive and unequal society under increasing state control. Rather, he is telling them to dream as patriots. When he urged students at Peking University to be patriotic like their May Fourth predecessors, Xi reminded them that ‘in present-day China, the essence of patriotism is to uphold the maximal unity of one’s love for the country, the Party, and socialism’.

In 1922, Lu Xun likened Chinese society to the unconscious inhabitants of a hermetically sealed ‘iron house’ 铁屋, walled in by the archaic and obsolete ideas of dynastic rule and wenyanwen, suffocating to death as they slept. Figuring New Culture and May Fourth as attempts to rouse some from their slumber, he asked his friend Qian Xuantong 钱玄同 whether any good could come of rousing these unfortunate few. The outcome would be only to alert them to the ‘agony of irrevocable death’ in an indestructible iron house. Qian replied: ‘But if a few wake up, you can’t say there is no hope of destroying the iron house.’21

In 2019, Xi’s administration intensified its aggressive measures to curtail academic freedoms, force-feed students Xi Jinping Thought, and punish the Party’s critics at mainland universities. It also incarcerated more than one million Uyghurs and people from other Muslim ethnicities in China in political re-education camps in Xinjiang. Justifying these actions as necessary for achieving the ‘Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation’ only makes sense if the ‘Chinese nation’ is merely a synonym for the CCP. In short, the China Dream tifa tells us the Party-state aspires to nothing less than an iron house in perpetuity.