Nepal Communist Party Chairmen Pushpa Kamal Dahal (left) and K.P. Sharma Oli (right) Source: Pradip Timsina-Think Tank, Wikimedia

ON THE SOUTHERN SLOPES of the Himalayas, in the shadow of Mount Everest, lies Nepal, a country that is remarkable for its rugged terrain and turbulent politics. A Hindu kingdom until 2008, the landlocked country is officially the world’s only secular federal parliamentary republic governed by a duly elected communist party, the Nepal Communist Party (NCP). In his second stint in office, which began in January 2018 (the first was in 2015–2016), Prime Minister Khadga Prasad ‘K.P.’ Sharma Oli forged an alliance with Nepali Maoists to guide the NCP to victory in the 23 January 2020 national assembly elections. Now he serves as co-chairman of the Party with Maoist leader Pushpa Kamal Dahal, whose nom de guerre is Prachanda (meaning ‘fierce’). They are presiding over the NCP at a time when it commands an absolute majority at federal, provincial, and local government levels.1

However, the NCP faced numerous crises in 2020 that could complicate its ability to govern effectively during this term and may compromise its comfortable majority in the 2022 elections. There is widespread popular criticism of the authoritarian, illiberal and hard-liner turn it took because of the alliance with the Maoists. It also faces accusations of discrimination against the Madheshi (lowland Terai peoples of Indian origin) and Dalit (so-called untouchable) people. Geopolitical tensions with India over contested territories and the need to balance relations with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) (its principal source of foreign direct investment) and India (one of its major sources of remittances) have added to its woes, as have Oli’s bungled handling of the COVID-19 virus in Nepal.2 Opposition critics in the social-democratic Nepali Congress party and Hindu nationalist National Democratic Party have grabbed on to every failure.

Even within the NCP, there are grumblings. Prachanda has already warned that the Party has grown distanced from the people and its ‘communist principles’, becoming ‘individualistic and power-centred’. In 2019 he argued that communism could fail in Nepal as it did in the former Soviet Union.3 The NCP, in short, faces a crisis of legitimacy. Although many of its leaders identify as Maoists, they are almost exclusively upper-caste, ethnic-majority men, and they seem to have discarded the ideology that drove them during the ‘people’s war’ of 1996–2006.4

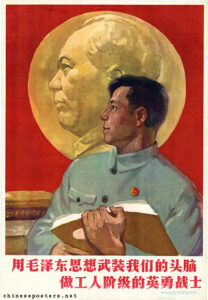

Arming our minds with Mao Zedong Thought to become heroic warriors of the working class Source: Zhou Guangjie, chineseposters, Flickr

Before the 2018 merger, the Maoist Centre, or CPN-M, was the more prominent of the two communist parties. It subscribed to Mao Zedong Thought 毛泽东思想, with its focus on applying Marxist-Leninist theory to concrete realities, guerrilla warfare, agrarian revolution, and anti-imperialism. Its charismatic leader, Prachanda, had twice served as prime minister, from 2008 to 2009 and again in 2016–2017, before the merger led to him sharing NCP leadership with Oli.5 The ‘Prachanda Path’ he developed during the war promoted ‘continuous revolution’ and opposed what he described as ‘right capitulationism and sectarian dogmatism’, which in the Nepali context indicated coexistence between capitalism and socialism, and the pervasiveness of conservative Hindu traditions — a compromise with which the NCP under Oli is more comfortable.6

The CPN-M is not the only Maoist group outside China to have gained state power: the Communist Party of Kampuchea, or Khmer Rouge, which ruled Cambodia under Pol Pot from 1975 to 1979, also seized power using Maoist methods. In Nepal, as in Cambodia, Maoism took hold during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders encouraged anti-imperial revolutions globally through the mass translation and dissemination of Mao’s works.7 The CCP tasked its Foreign Languages Press with translating Mao’s works for a global readership, which were distributed to more than 100 countries by Chinese embassy personnel and ‘progressive bookstores’ at virtually no cost.8

In Nepal, such books as the Quotations of Mao Zedong, Song of Youth, and Bright Red Star were soon, as Nepali translator Khagendra Sangroula (b. 1946) said in an interview, ‘everywhere in Kathmandu: wide and loud’ — and outside the capital, too. As a child, one Nepali Maoist recalled visiting a library in his hometown of Bhaktapur:

[I] told the librarian that I was interested in tales of bravery. They gave me a small book entitled The Life of Mao, through which I learned about Mao’s love of serving the people, his patriotism, the way he brought China forward.9

A curious readership soon developed into radical critics of, then active agents fighting against, the kingdom’s status quo. The 1951 Nepalese revolution, initiated by anti-monarchist political organisations in exile, had felled the autocratic, iron-fisted Rana dynasty (1846–1951 CE) and installed a brief constitutional democracy. But in 1960, the Royal House of Gorkha launched a coup that suspended parliament and banned all political parties. The Communist Party of Nepal (CPN, 1949–1962) fractured into factions, including one that was pro-China and another that was pro-Soviet.

The Nepali Maoists posited themselves as the ‘voice of Nepal’s poor and marginalised, the indigenous ethnic peoples, the lower castes, peasants, workers, students, and women’.10 In 1994, they formed the underground CPN-M, which aimed to topple the monarchy through ‘people’s war’ and to establish a ‘people’s republic’. They sent ‘political-cultural teams’ into the villages to mobilise the poor against oppressors such as landlords and police, and carried out land reform based on the violent Maoist model.11 The ‘people’s war’ began in earnest on 13 February 1996 after Nepali Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba (b. 1946) dismissed the Maoists’ list of forty demands, which included improving workers’ wages, narrowing the gap between rich and poor and eliminating the exploitation of and discrimination against women and ethnic minorities.12 The people’s war itself began in the mid-western districts of Rolpa, Rukum, and Jajarkot, where the Maoists had already established strongholds.13 It targeted, in the words of Deepak Thapa and Bandita Sijapati, ‘the most obvious signs of inequality in the form of local politicians, police posts, the judiciary, rural banks, and land revenue offices’.14 The CPN-M went from controlling three of the country’s seventy-five districts in 1996 to controlling forty-five in 2003, establishing ‘people’s governments’ in twenty-one of them.15

Although many villagers regarded the Maoists’ tactics as ‘positive’ forces for change,16 their experience of Maoism was mixed. The Maoists coerced villagers into joining their movement through conscription and threats of or actual violence, and even abducted children to serve as guerrilla fighters,17 reportedly luring impoverished Dalit children into their People’s Liberation Army with offers of food.18

More than 17,000 deaths later (nearly half of them Maoist), the conflict overthrew the royal autocracy and the CPN-M emerged as a major national political party of considerable influence.19 After party leaders signed the Comprehensive Peace Accord with the Government of Nepal in November 2006, Nepal became a federal republic.20 After leading three governments, the party merged with the NCP, which won government in 2018.

Before the merger, in September 2015, the CPN-M had drafted Nepal’s seventh constitution. Critics claimed that by failing, among other things, to outlaw gender discrimination and other forms of prejudice, the constitution failed to deliver on the Maoists’ promises of equality and higher standards of living. 21 Women and ethnic minorities had been among the Maoists’ most fervent supporters. Some estimates suggest as many as four out of every ten of its fighters and civilian supporters were women. Yet the Party’s rise to power did not result in women receiving promotions to leadership positions in the Party or in government; following the 2020 elections, only one of the twenty-two NCP ministers was a woman.22 As long ago as 2003, Maoist activist Aruna Uprety accused the CPN-M of ‘behaving no differently than our “men-stream” political parties’.23 Women made up one-third of the Constituent Assembly in 2008, but in 2020, Uprety’s criticism remains a valid one — despite the significant achievement of the country electing its first female president, Bidya Devi Bhandari.

Similarly, the new constitution failed to codify protections for ethnic minorities and oppressed castes, including the sixty non-Hindu Tibeto-Burman–speaking peoples and lowland Madheshis the Maoists had once courted.24 An ethnic Magar interviewee told a researcher in 2004 that he had joined the Nepali People’s Liberation Army partly because of ‘economic repression’ but also because, as an indigenous person, he had not been allowed to speak his language and suffered under other repressive policies of the Hindu government.25 In 2020, anti-Madheshi discrimination persisted and caste-based discrimination remained a major problem.26

Although Nepali politics were more stable than they had been for decades, these problems, and serious socio-economic inequality in general, remained unaddressed. As part of the ruling coalition, Maoists have abandoned more radical visions in favour of moderate approaches. This might help them stay in power, but in 2020, it seems increasingly unlikely that they will maintain legitimacy as the defenders of the poor and downtrodden.